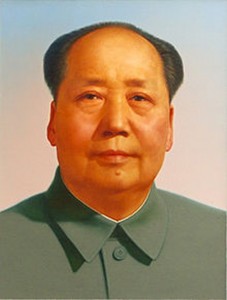

With his appeals to China’s sense of national greatness, Xi Jinping seems to be following in the footsteps of Mao. KERRY BROWN reports.

Meeting Chinese leaders, either at provincial or national level, is always a dramatic occasion for visitors. Governors or Party secretaries of provinces, or members of the Politburo or ministries in Beijing, receive people in splendid halls, with walls usually covered with scrolls of calligraphy or classical-style paintings, with chairs ranged around in a semicircle radiating out from the two most important people attending.

This can make even the hardest nosed foreign leader or business czar go slightly weak at the knees. As a diplomat serving in China, I was often struck by how seductive and sensual this side of Chinese diplomacy was, with its theatre, banquets and healthy doses of flattery.

Real power in China though is a more elusive thing. In recent months, commentators from President Obama downwards have been noting just how much power President Xi Jinping has managed to accrue to himself. He leads the Party, the military, and is head of state. He sits on four of the eight most important Leading Groups where the most crucial policy decisions are made, where he acts as chairman. From foreign affairs, to domestic development, his fingerprints are everywhere. With the current anticorruption campaign, Xi has also forged new discipline in the Party and made it more attendant to his political will. Surely, this man is powerful?

Like the attendees of those grand meetings of VIPs mentioned above, however, we have to be careful not to mistake the outward trappings of power in the modern People’s Republic of China (PRC) for the real thing. Deng Xiaoping, over three decades ago, wielded immense authority, and his shadow still casts itself across the country. Xi himself has worked almost completely within the framework of reform Deng created. And yet Deng was never more than a vice-premier after 1978, and from 1982, only chair of the Military Commission. His influence existed in moral and ideological control. Xi is very aware of this, and has made concerted efforts to show that he too has some claim on these less tangible but far more profound modes of power. His book, The governance of China, published late in 2014, is, early on in his time as national leader, an attempt to stake this territory out. It has lengthy sermons on the need for cadres to act selflessly and with humility on behalf of the people, to live up to the moral ideals of the modern Party, and to appeal to China’s traditional cultural assets as a basis for its values propositions.

It also invites political leaders to forge a new social contract with society. This is not just a transactional relationship where the Communist Party allows people to become materially rich, and they repay it with skin-deep loyalty; it is something far more complex where both sides have a shared vision—what Xi has somewhat abstractly tried to express as `the China dream’.

Power in China, like anywhere, flows along two basic routes. There are the external carriers of it—the Party itself and its various institutions and constituent parts, then the government, and the military, state enterprises etc.

The claim that China is no longer a society where ideology matters is belied by the fact that there are over 2000 party schools across the country teaching this very thing to cadres.

Most agree that the Party has the broadest remit, and the most privileged role, in charge of what is somewhat hazily called `the leadership direction’ in society. This means the Party’s leading bodies—from the Politburo down—can roam where they want, influencing personnel, budget and policy decisions.

Alongside this are the other, less tangible forms of power and influence—ideology, narrative and emotion. The Party spends a lot of time on all of these. Ideology, justifying why things are done the way they are, is far more important than many people think.

Narratives important

The claim that China is no longer a society where ideology matters is belied by the fact that there are over 2000 party schools across the country teaching this very thing to cadres, and the political super elite spend so much time ensuring their pronouncements at least conform to Marxism or are seen as local developments and contributions to it. Narratives are important in explaining how the Party and its various leaders have come to power, why their authority is good for China and its people, and where they are leading the country as it travels towards `rich, prosperous and strong’ status, its stated aim in the next decade or so.

Emotion is the least easy form of power to define. In China, especially in the era of Hu Jintao, most would have said that, from the way elite leaders talked then, there was little role for emotion. Political speeches were solid blocks of statistics and data, focusing relentlessly on numerical deliverables, from GDP growth to export figures and industrial output. How would anyone grow emotional after listening to this?

Except, of course, that emotional engagement between leaders and the led is hugely important and cannot be ignored. It is probably the most potent form of all power, all the more so because of its intangibility. And there are good reasons to say that, at least for the first decades of the PRC’s existence, politics was more about emotions than rational policy considerations or institution building and reconstruction.

Mao Zedong (pictured) was the supreme master of this form of politics, someone whose hold on the imaginations of Chinese people was so complete that, despite immense failures like the Great Leap Forward of the late 1950s, the famines that followed it in the early 1960s, and then the turbulent nationwide catastrophe of the Cultural Revolution from 1966, his hold on power was secure till his death in September 1976. He spoke to the hopes and aspirations of Chinese people, telling them to look and hope beyond the misery of today to a wonderful future when everything would be fine. This was an intoxicating message. Most fell for it. Some still do.

Because of Mao, and the unfortunate consequences of his highly emotional, idealistic style of politics and power, leaders after him have been very wary of stirring up the feelings of Chinese people. But with Xi Jinping, there are signs that his appeal to a sense of national greatness and status returning to China, and creating a proud, strong country with a magnificent and ancient culture are part of an attempt to move beyond political success being not just about delivery of tangible growth statistics, but a sense of pride, and emotional satisfaction among people. Only these emotional, sometimes nationalistic messages might have widespread appeal.

He might not have much choice about moving in this direction. Growth in China is slowing and becoming more complex and harder to produce. The public are disunited, with huge differences in wealth and development levels. Social media and the internet might be controlled in China, but they have given a vast number of people the ability to create their own networks, and broken down the idea that the country belongs to one solid viewpoint.

China is truly a social carnival now. Only these emotional, sometimes nationalistic messages might have widespread appeal. The only problem is that they are hard to control, and they tend to panic the outside world, certain that it divines in these messages aspirations by China to be a new global force competing with the United States.

When we look at China in the coming years, we are almost certainly going to have to look beyond the tangible trappings of power to the troika of intangible ones—ideology, narrative and emotion—described above. It will be Xi Jinping’s mastery of these, more than his ability to hold positions with the party and government apparatus, that most matters.

Up to now, he has shown a far greater confidence in these areas than his predecessor. But these are early days. And no one, least of all Xi Jinping, really knows what a return to more emotional politics and power in China might really look like.

Main photo:

A fire dragon dance during Chinese New Year celebration (China Wikimedia Commons).