Fifty years on, many Indonesians involved in the massacres of communists following an attempted coup have no regrets about their role in the killings. NICHOLAS HERRIMAN and MONIKA WINARNITA explain.

Last month the Indonesian government banned several sessions at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival that had been set to discuss and launch important new books about the massacres of communists in Indonesia between 1965 and 1967.

The bans, however, were not the action of a sinister, authoritarian state intent on covering up a dark secret. Instead, we need to look at the international, national and local issues that formed the context of the massacres, which take a place among the mass killings of the 20th century.

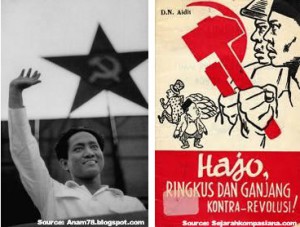

The pretext for the killing and detention of hundreds of thousands of alleged members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) was an attempted coup, on 30 September 1965, for which the PKI was blamed—accurately, it now seems. Following the coup attempt, killings occurred in many places, particularly central and east Java around October and Bali in December, and elsewhere in smaller numbers, running into 1966 and 1967.

As part of the Cold War politics of the time, the United States had emerged as a belligerent superpower, with China and the former USSR looking equally hostile. Indonesia had the world’s largest communist party, outside of the USSR and China. The ‘fall’ of China to the communists and the wars in Korea and Vietnam convinced many in the West that they would need to battle for freedom against an evil empire—even to the extent, as in the case of the United States, of tolerating dictators whose only credential was their harsh stand against communism. Such support probably bolstered the position of the killers in Indonesia.

Particularly culpable for the killings in Indonesia was the general who emerged from the attempted coup to be the country’s military dictator—Soeharto—and those loyal to him. Sections of the armed forces loyal to Soeharto detained or killed tens of thousands of communists, while those sections that sympathised with the Communist Party were promptly subdued. Military newspapers and other media urged little mercy for the ‘depraved’ communists.

Equally responsible for the killings were large numbers of civilians. Years of tension between communists and anti-communists devolved into a mutual sense of kill-or-be-killed in many areas. Almost everywhere, those identifying as religious, patriotic, and/or nationalist Indonesians shared a fear or unbridled hatred for the ‘atheist traitors’.

Of the many anti-communists from this period that we have got to know personally, some were actively engaged in demonstrating against communists; others were actively engaged in killing them. Some were encouraged, and even trained, by the armed forces. Dreading the communists, most just went ahead, with implicit support from the army. None of these people regret their actions, and most are proud of them.

Other scholars have noted that, even if the military had played a passive role, the level of violence might still have occurred, as much of it was the result of locals killing other locals—even their neighbours and members of their own family. In some areas, civilians were so over-zealous in their efforts to obliterate communists that Soeharto loyalists had to threaten them with violent reprisals if they did not stop.

Bali killings

The arrival of anti-communist troops in Bali early in December 1966 was crucial in inciting the massacres on the island—yet the troops also, reputedly, later attempted to restrain the killers. Thus the killing of communists was no Stalinist ‘Great Terror’ or Nazi Holocaust: they went ahead with widespread popular support and engagement.

A famous Oppenheimer film, The Act of Killing, depicts thugs enjoying their part in the massacres—a patriotic act against atheist traitors. Approached by the thugs for support, the local army does not want to know or be associated with them. Nevertheless, these thugs—as more ordinary killers do in other places—seem to consider themselves heroes.

The CIA, and maybe the Australians, and who knows who else apparently provided information about the PKI to the Indonesians. It’s just conjecture, but we imagine the Indonesians who received information would have appreciated the moral support. Whether it was of any use to the killers is another point. For the most part, the killers probably felt they knew only too well who the communists were—it was no secret. Communists had been increasingly vocal and threatening in the years leading up to the massacres, and to emphasise the role of the CIA or other international governments, as some western accounts do, is simply hubris.

So how do Indonesians view the killings today? We can’t pretend to understand or speak for the majority of Indonesians. All we can do is try to interpret aspects of life in this nation of 250 million.

Most Indonesians we have lived with—and still associate with—believe the Communist Party had it coming.

Can one even speak on behalf of the victims of killings and detentions? How can we address the unfathomable suffering for them and their families? Even those alleged communists who survived had their lives ruined. Their cause profoundly affected intellectuals, artists and the left. A pervasive sense of barbaric injustice still dominates their outlook.

Nevertheless, most Indonesians we have lived with—and still associate with—believe the Communist Party had it coming. They hark back to the attempted communist revolution in 1948 during Indonesia’s struggle for independence against the Dutch. The communists, they assure us, were atheists who had betrayed Indonesia during its revolution. They were planning to take over Indonesia and spread evil atheism. So, even today, there is a sense that to be a patriotic Indonesian is to be anti-communist. This is why the massacres of 1965–67 are still commemorated in Indonesia: the anti-communists feel they saved the nation.

It is hard for many people in the West to understand. But, tellingly, at the time the West vigorously approved. Time magazine, for example, hailed Soeharto as ‘the West’s best news in years’.

One analogy is that of the Vietnam war. The effects of the defoliant Agent Orange on Vietnamese children and veterans are on our agenda, but the killing of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians is largely overlooked. At memorial services and parades we don’t consider it appropriate to dwell on this.

Our analogy, however, is limited. Many regretted the killing of Vietnamese, then and now. In Indonesia, by contrast, many believe that those who killed communists saved the nation and should be commemorated, like the revolutionaries who fought the Dutch.

Indonesian authors and intellectuals, like their western counterparts, thrive on frank and open discussion, and would question the common opinions about communists and the killing of them. But generally, openly confronting and criticising aspects of the past, has not gained much traction in Indonesia.

Yet all this only provides context for the recent bans at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival sessions. The officials responsible probably had other concerns—such as promoting Bali as a respectable international tourist paradise. Their concerns over the sessions relating to the events of 50 years ago were probably more akin to their desire to hold a ‘Miss Universe pageant’—without the swimsuit poses. Indonesia wants a certain image in the world and controversy negates this.

The attempt to hush up the massacres by banning the Ubud sessions has had rather the opposite effect to that intended. News of the bans made the front page in the English edition of Indonesia’s premier news magazine, Tempo, as well as attracting some media coverage in Australia.

The bans have put the massacres back under public scrutiny—where, we hope, they will remain.

Dr Nicholas Herriman is a senior lecturer in Social and Cultural Anthropology at La Trobe University.

Dr Monika Winarnita is a postdoctoral researcher with the University of Victoria, British Columbia. She has an external affiliation to La Trobe University. Her thesis is on Indonesian migrants in Australia.

Main photo:

The Pancasila Sakti shrine in Jakarta to the six army generals murdered on the night of the coup, 30 September 1965 ( (Flickr/Chez Julius Livre 1 CC)

Related articles

Guilt and shame linger over Indonesia’s 1965–66 killings