Popular culture in Indonesia exposes divorced or widowed women to prejudice and stigmatisation, writes NICHOLAS HERRIMAN.

One of the most popular and enduring images of femininity in Indonesia is the janda. The term refers to either a widow or a divorcee because, in the popular imagination, how she has become unmarried is not particularly relevant. The main point is that she is no longer married.

The janda contrasts with popular images of the maiden and the mother. Her image also emerges from popular ideas of fate, desire and shame. She is imagined to be sexually available and lascivious. She is a fascinating object of desire, but descriptions of her also evince a sense of pity. The equivalent male image of the divorcé or widower (duda) is vaguely defined and mostly irrelevant.

The janda is imagined in salacious detail, making it impossible to describe her without delving into some ‘unsavoury’ detail. The janda of the imagination, like the West’s femme fatal, the witch or the ‘California girl’, exists in the cultural realm—not as a description of an actual group of people, but as a stereotype. This is a stereotype that, in the real world, women who are widowed or divorced throughout the Indonesian archipelago have to confront.

Recently, the janda has appeared repeatedly in metropop. Inspired by the US hit television series Sex and the city, metropop is a genre of Indonesian literature which portrays the lives of young women in the city. In some titles, like Divortiare and Janda-janda Kosmopolitan, the heroine is a janda, and the story depicts her experiences as such.

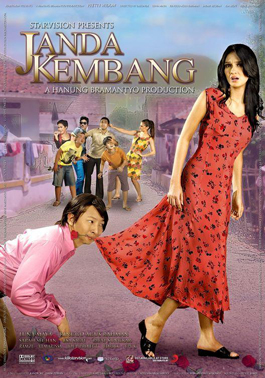

We also see the janda portrayed in dangdut, an Indonesian music style that combines Arabic, Indian, and western elements. Live dangdut concerts are literally a riot of fun. An attractive woman in sexy attire will sing a song bemoaning the sad figure of the janda, while young male dancers cavort onstage with the female singers. This betrays the more titillating aspects of the song—that the pitiable figure of the divorced or widowed woman not only desires sex but is available for it. Although the janda is portrayed most fulsomely in dangdut music, the image also appears in recent movies such as Dying young in a janda’s embrace and Flower janda .

The janda trope must be understood in terms of two other figures; the maiden and the mother. The maiden, as portrayed in popular culture, is shy and retiring. She must be modest and guard her virginity. She can flirt and be the object of desire, but only as a means to get married and have children. Once she has children she becomes the idealised figure of femininity, the mother.

The wife–mother (Ibu) symbol is soft and gentle, devoted and affectionate. She raises her children for the good of the nation. Her sexuality is creative in terms of making a family. It is also binding. Her attractiveness keeps her husband loyal, especially in the face of the greatest threat to the compact family, the janda.

In contrast to the maiden figure, who is sexually available to nobody, and the mother symbol, who is sexually available only to her husband, the janda is conceived of as available to anybody. She is portrayed as pitiable and laughable, hoping vainly that a well-meaning man might marry, thereby obtaining for himself heavenly reward as well as a second wife.

The janda also relates to culturally specific ideas of desire, shame, and fate. Desire in Indonesian popular culture—particularly for food, drink and sex—is thought of as healthy and essential. Without desire we would not sustain ourselves or reproduce. Indeed, husbands and wives would not have sex, threatening their marriage and their reproductive potential, and children would not grow. To be lacking in desire is a lamentable state.

Husband’s desire

The husband is thought of as being equipped with desire. His wife’s job is to attract it. If she fails, it will probably be a janda who attracts his desire, thereby threatening the family. The reason is that sex outside marriage is sinful; but sex with a janda is thought of as a kind of loophole, because she is no longer a maiden and doesn’t have a husband.

What makes the janda figure even more attractive to men is that she is also very desirous. It is believed that, just as she was getting used to fulfilling her ample desires, she was left single and yearning. This makes her a threat. Thus the husband’s desire, properly harnessed by the wife, can be creative. But if she cannot properly control it, he may succumb to a janda, destroying the family and transforming his wife into a janda. The wife’s sexual attractiveness to her husband, therefore, possesses a strong normative element. Little wonder then that, in the real world, certain popular medicines such as asli Madura can help wives increase their sexual appetite which, in turn, will satisfy their husband.

Fate and the Janda

Fate (nasib) also is important in understanding the janda. It is not the woman’s fault that she is divorced or unmarried; it is God’s will. She must accept it. Two famous dangdut songs are entitled ‘Fate of the janda’. In one, the singer laments:

Hey, everything’s messed up if you’re a janda …

The fate, yes the fate,

This is the fate of a janda.

She has become a janda not through anything she has done—yet, according to cultural conventions, being a janda is her humiliating fate. This shame is the stigma that the imagined janda must bear. For example, in the song called ‘Maiden or janda’, a man who is seducing a woman asks:

Are you a maiden or are you a janda?

Just tell me, don’t be embarrassed

There is always a suspicion in popular cultural portrayals that the janda might be available if the price is right. And this adds to her disgrace and attractiveness in equal measure. Thus in the context of desire, fate and shame, the janda is portrayed as sexually available and lascivious.

Because of the janda image, divorced or widowed women in Indonesia face substantial prejudice and stigmatisation. It is therefore important to document their experiences—but before that, to analyse the nature of the stereotype they confront.