Love and marriage in today’s China are increasingly being conducted in the spotlight

If not bread and butter, television dating shows have become an important ingredient of the Chinese diet.

For singles, they are a platform for seeking potential spouses. For the mass audience, they are a topic for gossip. For the cultural elites, they are a subject for interrogation. And for the government, they are a target for surveillance.

Studying the development of television dating shows helps to understand how the concept of love and marriage in China has changed, and how the shows are helping bring about that change.

Dating shows began emerging as a new form of marriage matchmaking in China in the late 1980s. The first dating program, Television Red Bride, aimed to ‘serve the people’ by helping individuals, especially males of rural and low socioeconomic backgrounds, to find a partner. The nature of the show echoed the strong imprint of the communist ideology initiated by Mao Zedong in 1944

The show’s male-oriented nature reflected China’s sex ratio imbalance, in part caused by the one-child policy and the dominance of patriarchal values.

Although China launched its ‘opening up’ policies in the late 1970s and re-emphasised marriage freedom and gender equality in the 1980 marriage law, the first girl to appear on Television Red Bride was still condemned by her family for losing face in public. The family’s reaction reflected the continuing traditional belief that women belonged in the domestic sphere and should obey their parents in terms of the marriage decision.

Basic formula

Television Red Bride followed a basic format: candidates introduced themselves, outlined their marriage criteria, and answered a few questions from the host. Despite its limitations, the show signified another ‘great leap forward’, revolutionising the way marriage-seeking was conducted in China.

With the acceleration of marketisation and globalisation in the 1990s, the situation began to change. Facing strong competition, media outlets were under pressure to produce programs that not only had commercial value but were also entertaining. Dating shows, such as Dating on Saturday, Love at First Sight and Red Rose Date proliferated and adopted a reality format where male and female marriage seekers showed their talents by interacting in groups and playing games. Audiences were also able to watch imported shows such as Love Game, from Taiwan.

The commercialisation of the television industry in the 1990s thus nurtured an intersection between love, romance and entertainment, and motivated mass audiences to also participate in dating shows. This not only answered the government’s call for greater freedom to love and for gender equality, at least on television, but also brought about a reconceptualisation of love, courtship and marriage in Chinese society.

Love, marriage and commerce have never been brought so closely together.

This has become even more prominent since the mid-2000s when dating shows seeking new ways to attract audiences in order to compete with other types of entertainment programs introduced new hosting styles and techniques appropriated from Western reality television.

The shows also began collaborating with online dating sites to broaden the number of the recipients and partnering with big enterprises to boost advertising revenues. It is not uncommon to see images and brands of commercial products like electronic cookers, smartphones and soy milk makers on these programs, and for the hosts to mention the names of businesses. Love, marriage and commerce have never been brought so closely together.

Ratings boost

Whether intentional or not, dating shows have also boosted their ratings because of media criticism of the attitudes of some hosts and contestants. Comments such as ‘I’d rather weep in a BMW than laugh on a bike’, ‘I won’t think about it if your monthly salary level is under RMB 200,000’, and ‘I won’t consider those who come from the countryside’ have been strongly condemned for their materialism, self-centredness and discrimination by the younger generation against the poor, and for commercialising and stigmatising the ideal of love and marriage held by earlier generations.

In 2010, SARFT—the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television—intervened for the first time to curb dating and love-themed programs in an effort to reassert of the state’s right to control and censor private intimacy in ‘neoliberal’ China. The official message is clear: the Chinese people need the freedom to love and marry—provided it doesn’t cross the boundary of socialist values.

Just like yin and yang in traditional Chinese thought, the juxtaposition of neoliberalism and state authoritarianism might seem contradictory, but essentially they complement each other by creating a space for discussion among opinion makers, elite groups, scholars, the media, the government and the masses.

Although no consensus has been reached, the process has enabled the nation to discuss, debate and further comprehend what love and marriage means in today’s China—and to negotiate a balance for the future.

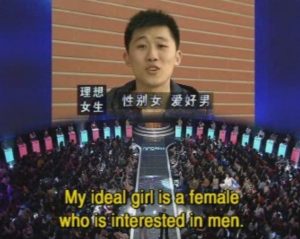

Featured image:

A man proposes marriage to a woman on the dating show If You Are the One. Photo: This is Beijing