with contributions by Martin M. van Bruinessen, Richard Castles, Barbara Leigh, Michael Leigh, David Mitchell, Halina Nowicka, Anthony Reid, and Heather Sutherland.

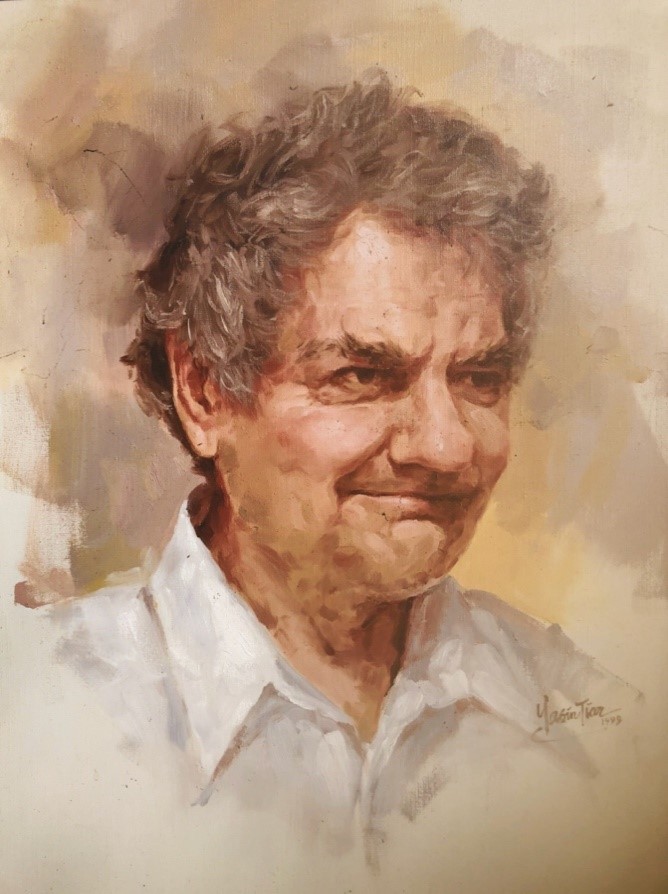

Lance Castles died peacefully in Melbourne’s Highgrove Aged Care home on 27th August 2020, his mind remaining lucid to the end. He was a pioneering and insightful scholar of the history, economics and politics of Indonesia.

After graduating from Melbourne and Monash universities, Lance went to Jakarta in 1963 as a research assistant in the University of Indonesia’s Institute of Economic and Social Research, a challenging job that was immensely satisfying to an idealistic graduate wanting to make a difference. He was committed to the Australian Volunteer Graduate Scheme in Indonesia which determined the course of his life, most of which he spent in the country he learned to love.

In 1963-64 he did three months’ field work in Kudus, Central Java, which became the basis of his Monash MA thesis (1965). In 1964 he worked as a research assistant at ANU’s Research School of Pacific Studies (RSPS), then took up a PhD scholarship at Yale University where Professor Harry Benda had accepted a chair in Southeast Asian History.

Southeast Asian historian Anthony Reid wrote: “It is easy to imagine that Harry Benda seized with delight on his Australian graduate student with an uncanny knowledge of Javanese society, and encouraged, even perhaps obliged, him to publish… Before switching to Sumatra for his dissertation, therefore, Lance was already the best-published young scholar of his generation on Javanese society”.

At Yale, Lance published an article on the Islamic School in Gontor (1966), and a booklet: Religion, Politics and Economic Behaviour in Java: The Kudus Cigarette Industry (1967) which enjoyed an accolade from leading scholar Clifford Geertz (1968):

In less than a hundred pages Lance Castles has managed to bring an extraordinary number of basic dimensions of contemporary Indonesian culture, society and economy into concrete relationship with one another, and to do so in the guise of a specialised study of …a small and not terribly important town in northern Java. The phrase tour de force…would be the appropriate term to apply to Mr Castle’s closely argued and marvellously compressed book. It is a startling achievement.

Lance’s 1967 article on the transformation of Jakarta from colonial capital in 1931 to the multi-ethnic national capital of 1961 is still well worth reading, writes David Mitchell. Jakarta was a creative crucible where Sundanese, Javanese, Chinese and Batak populations were combining to develop a new Indonesian identity. God was making a new kind of Indonesian, he said. However, after the article was translated and circulated in Jakarta in 2006, it became somewhat controversial.

Anthony Reid, then at ANU’s Research School for Pacific Studies, was looking in the 1960s for Southeast Asian historians to explore a new frontier beyond the excessively British, European and Australian focus of Australian universities. “To my delight”, he wrote, “Lance wanted to come home, and applied for the first 3-year Southeast Asian research fellowship I was able to steer through the committees in 1972. How could I not be impressed? With a newly minted PhD, he already had several wonderfully informative and influential publications, far ahead of any of his peers. He seemed to show a wonderful knack for identifying a fascinating subject, getting right inside it through a mix of written data, statistics (which he handled better than most historians), meticulous fieldwork, and writing an exemplary report.”

In the 1970s Lance published a series of articles and, with Herb Feith, the influential anthology of political texts: Indonesian Political Thinking, 1945-1965.

But Lance was looking beyond Java to the great island of Sumatra. In 1972, he obtained his PhD at Yale with a thesis on “The political life of a Sumatran residency: Tapanuli, 1915-1940”. As Martin van Bruinessen noted, “a group of Batak intellectuals considered Lance’s dissertation on Tapanuli as perhaps the best study of their history. Photocopies of the dissertation were treasured as precious possessions, lent only to trusted friends. Lance was often asked to have it published, but in his own view it was not good enough yet… But he could not prevent the circulation of photocopies, and finally assented to publication of an Indonesian translation in 2001”.

In 1975 at ANU, Lance published a paper on pre-colonial Batak society (in Reid and Castles, eds.). As David Mitchell writes, “It describes pre-colonial Toba Batak society as stateless, without the institutions of rulership. This bold concept was very useful in understanding older Austronesian societies surviving before the arrival of Indic, Islamic and colonial influences. On the island of Sumba traditional life was very much like the Bataks’ – a world of villages without towns or cities, and no palaces either. Lance provided a clear and logical model that fitted well for many other stateless communities encountered in Sumba, Timor, Toraja, and upland Southeast Asia”.

While at ANU, Lance was attracted to a challenging position in the Social Science Research Training Centre (PLPIIS) at Syiah Kuala University in Aceh. As Michael Leigh explains, it trained twelve young researchers from other provinces of Indonesia in fieldwork-based social science research. Lance made a huge contribution as a specialist lecturer, mentor and guide to the trainees from 1976. Not only was he fluent in the Indonesian and Batak languages, but he immediately set about learning Acehnese. Lance also discussed theological matters with local ulama, drawing on his knowledge of sacred texts in Arabic, Persian, and Acehnese. This was greatly appreciated in Aceh where he was affectionately known as “Teungku Lance”(an Acehnese honorific for ulama [cleric]). Lance lived in a house with Acehnese students and entertained many visitors. He once commissioned a performance of the seudati song-dance, as Barbara Leigh remembers. Until the early 1980s he taught at the Ar-Raniri Institute of Muslim Religion and did research in Aceh’s Save the Children office.

In 1982 Lance was involved in the Postgraduate Program at the University of Indonesia, enjoying the travel to select potential postgraduate students. As Halina Nowicka writes, a number of young Acehnese were living and studying in his house, where he cooked and provided hospitality for people who wished to talk to him.

In 1988 Herb and Lance published their reader: Indonesian Political Thinking 1945-1965 in Indonesian translation. However, “it was too “political” for the depoliticising New Order and could only appear after the publisher had removed all references to communism. As van Bruinessen commented, Indonesian students who knew about the book sought out Herb and Lance and found in them mentors who would discuss politics in ordinary language, without the verbose euphemisms and dissimulations of New Order talk. Lance’s house in Jakarta was often visited by student activists who were an important source of information and to whom he was a patient listener and cautious adviser, willing to discuss matters they could not discuss with other lecturers”.

In 1988, Lance moved to Yogyakarta to teach at Gadjah Mada University, and Herb and Betty Feith stayed in his home. Like them, as van Bruinessen observed, Lance felt obliged to make their research and teaching useful to the society they studied – to human rights, democratisation, and empowerment of the oppressed. They cultivated relations with former political prisoners and student activists and helped them where possible. Their attitude to work and daily life was deeply religious, although they did not practise any formal religion.

When Lance moved back to Melbourne in the early 2000s he was very ill. After he recovered, he often came to Monash and allowed the present author and an Acehnese PhD student to draw on his deep knowledge of Acehnese language, literature, and history for their research on Acehnese music and culture, and they joined a chorus of scholars forever grateful for his insights and intellectual generosity.

In 2004 Lance studied Indonesia’s presidential election in Indonesia, and published The 2004 Election in Comparative and Historical Context (2004, in Indonesian) and an article ‘Why and how did SBY win?’ in The Year of Voting Frequently: Politics and Artists in Indonesia’s 2004 Elections (2005, ed. Kartomi). Lance was involved in local political debate, staying up to all hours, writing short pieces for his network of friends. Noting how elevated his mood was, David Mitchell asked about the role of mood swings in his life: did he have depressive episodes too when he withdrew from society and his friends did not know where he was? “But Lance would have none of my psychiatric speculations”, David wrote. “To him these were just times when he was very lethargic due to poor physical health or had disappeared into the archives for weeks or months on end. Just the way his life went”.

Lance spent the last two years in Highgrove Nursing Home where he listened to classical music – especially Bach, Handel, Beethoven, and Brahms, and read the Bible, the classics, and poetry. He owned and read Bibles in German, Greek, Russian, Hebrew, Javanese, Urdu and Tagalog, and also Qur’ans in Arabic, Persian, Javanese, and Indonesian.

Eulogies at Lance’s funeral were accompanied by recordings of sacred and secular music, ending with Handel’s uplifting Hallelujah Chorus.

+++

For a longer obit with a bibliography see Inside Indonesia (Sept 14, 2020).