Alexander Brown is the author of the newly-released book ‘Anti-nuclear Protest in Post-Fukushima Tokyo: Power Struggles’ with the ASAA East Asian Series published by Routledge.

Since the election of the LDP-Komeito coalition government in December 2012, the government’s introduction of controversial legislation to protect state secrets and expand the role of Japan’s military in external affairs as well as attempts at constitutional reform have provoked regular outpourings of public protest outside the National Diet in Tokyo. These demonstrations have taken place in the same location as mass protests against nuclear power that occurred in the wake of the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster and played a key role in revitalising street politics in Japan and drawing a new layer of young activists into protest politics.

When the anti-nuclear movement reached its peak on 29 June 2012 during protests against the restart of a nuclear reactor at Oi in Fukui Prefecture, an estimated 200,000 people took part. These were the largest street demonstration to take place in the archipelago in more than fifty years. The roots of this movement lay in a diverse coalition of activists concerned with issues as varied as precarious work, Japan’s peace constitution and historical memory issues as well those who had longstanding concerns about nuclear power. These movements, which grew during the 1990s and early 2000s, reinvented and refashioned protest to produce colourful protest-performances where the city was reinterpreted as a space of democratic participation. As Japan’s political, economic and cultural capital, Tokyo was at the centre of the new wave of anti-nuclear activism.

The first major demonstrations against nuclear power took place after Fukushima took place in Tokyo’s Kōenji district in April 2011, one month after the disaster. Kōenji is a youth sub-cultural hub located close to downtown Tokyo which is known for being a major hub of artistic, musical and cultural life. The district is also home to activist network Shirōto no Ran (Amateur Revolt), whose creative and irreverent protest style developed in struggles against the growing inequality experienced by the urban poor following the recession of the 1990s. After the tragedy of the March 2011 earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster, a ‘mood of self-restraint’ (jishū) prevailed in the capital. The festive demonstrations organised by the group helped to shift this mood, claiming a space where participants could express a wide spectrum of affective responses to the disaster. Shirōto no Ran’s critiques of precarious work and of the inequities of neoliberal capitalism fed into their anti-nuclear activism after the Fukushima disaster leading the group to critique the energy-intensive consumer capitalism for which Tokyo has become a global symbol.

In the years prior to the Fukushima disaster, activists associated with Shirōto no Ran and similar networks had established bars, cafes and bookshops that constituted a loosely organised activist kaiwai or neighbourhood. These places provided a space for anti-nuclear organising and for cementing the relationships between activists which sustain political action over the long term. The neighbourhood also generated a diverse print and electronic media that was produced in and distributed through these physical spaces and helped create a sense of community among activists, artists and the disenfranchised. These spaces emerged in the context of rising inequality and urban poverty after the collapse of the bubble economy. They enabled part-time, casual and freelance workers and alienated youth to seek refuge in the interstices of a city from which they often felt excluded. After Fukushima they provided a kind of asylum in the uncertain context of a radioactive city.

While activist spaces were places of refuge after the disaster, activists did not simply disappear into them but sallied forth into the public streets which they transformed into a theatre of protest. During two protests in Shinjuku in June and September of 2011, anti-nuclear activists occupied the east exit plaza of Shinjuku station, which they renamed ‘No Nukes Plaza’. They deliberately invoked the pre-existing notion of a hiroba (plaza) in their efforts to redefine public spaces such as the consumer paradise of Shinjuku station as places for democratic practice and debate. No Nukes Plaza evoked a history of struggles for public space in Tokyo. Shinjuku station had long been a site of student and peace movement protest made famous by the so-called ‘folk guerrilla’ movement of the late 1960s which saw activists occupy the west exit hiroba on a weekly basis to hold political discussions and sing folk songs. Struggles to reclaim public space in turn raised questions about the limits of democratic participation imposed by the police and on the degree of internal heterogeneity activists themselves could accept.

The debates on democracy which occurred in and through the hiroba were not limited to the national space but were discursively linked with a global network of squares and public places where similar actions took place in 2011 and 2012 including the Occupy Wall Street camp in New York’s Zuccotti Park and the Spanish 15-M Movement’s occupation of public plazas in Barcelona and other cities. Nor were the demonstrations in Tokyo confined to large central actions in Shinjuku or Chiyoda wards. Local demonstrations were also organised by residents of municipalities across the metropolis. In Kunitachi in Tokyo’s western Tama region, demonstrators performed their opposition to nuclear power in colourful costume demonstrations that were themed according to seasonal festivals such as the bean-throwing festival Setsubun in February 2012 or Halloween in October in an attempt to naturalise the idea of demonstrating and align it with the normal rhythms of everyday life. Like the demonstrators at No Nukes Plaza in Shinjuku, these protests were situated within a global imaginary through references to the music and film of the feminist anti-nuclear weapons movement at Greenham Common, England in the 1980s and 1990s.

Beginning in March 2012, activists gathered outside the prime minister’s residence in Tokyo’s Nagatacho every Friday evening between six and eight o’clock to protest nuclear power. These weekly protests eventually led to the mass demonstration mentioned at the start of this article. By protesting outside the buildings which house the institutions of the government, the protests highlighted two different visions of politics: one centred on the formalised representative democratic structures of the state and the other on grassroots participatory democracy. Their staging in the government district revealed a tension between horizontal and vertical conceptions of politics and acknowledged the continuing importance of institutional politics in Japan today. Anti-nuclear protest transformed the order of public space in the city and reclaimed it as a place where citizens could participate in politics. Activists’ diverse tactical interventions suggest a wider strategic vision of the city as a space for creative self-expression, sustainable livelihoods, strong communities and grassroots democracy.

For many anti-nuclear activists, the return of the pro-nuclear Liberal Democratic Party coalition under the leadership of Prime Minister Abe Shinzō in 2012 was a major disappointment. In reality, however, the change of government produced little real change in terms of nuclear policy. Neither major party was willing to make nuclear power into an electoral issue in 2012 and the successful LDP election campaign instead focused on economic concerns, thereby taking the political sting out of the nuclear issue. This is a strategy that has continued to serve the LDP well, particularly in the context of historically low levels of voter turnout. Despite the Abe government’s publicly stated intention to proceed with reactor restarts once safety checks are complete, restarting Japan’s nuclear fleet has proved to be extremely difficult. Many nuclear reactors failed the stress tests that were introduced by the Kan government after Fukushima. Others require extensive and expensive retrofitting and upgrading in order to meet the stricter safety standards which were adopted by the new Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA). Where final approval has been obtained from the NRA, other delays such as objections from local political leaders or successful court challenges have further impeded the restart of the reactor fleet. At the time of writing in June 2018, only seven reactors have been restarted. This is compared with the 54 that were operating before the 2011 disaster. Public opinion polls indicate that opposition to a return to nuclear power in Japan remains firm.

Since the election of the Abe government in December 2012, Abe’s neo-nationalist and militarist agenda has generated many new protests in the streets of Tokyo. When the government moved to introduce a raft of security-related legislation in 2014, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets outside the National Diet. As the nuclear issue began to fall out of the news cycle and other issues took its place, the new common sense developed through the collective experiences of the anti-nuclear movement informed a new wave of protests. The experience of anti-nuclear protest rejuvenated civil society in Japan and schooled a generation of young people in street politics. These actions suggest that a new culture of protest, most clearly visible in these large-scale actions in the government district, has taken root in Japan since the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

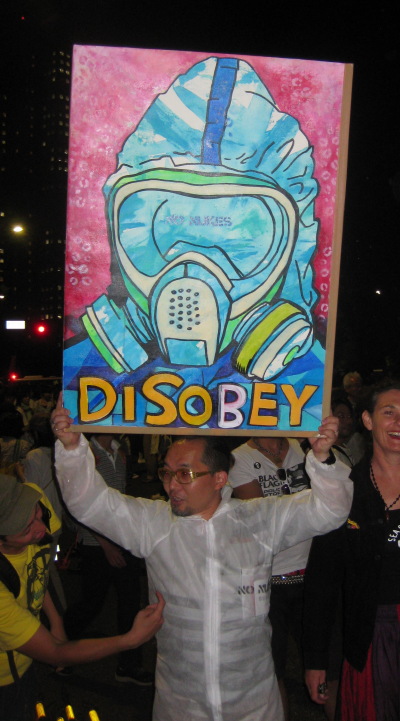

Featured image: One Year Anniversary Demonstration, Chiyoda Ward, 11 March 2012, all photos are the authors.