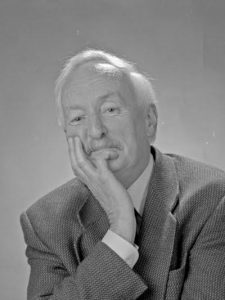

Emeritus Professor Nicholas Tarling

1931–2017

Anthony Reid remembers Nicholas Tarling, a man of many parts—but above all, the most prolific Southeast Asian historian of this or any age

Nicholas Tarling died in the water on 13 May aged 86, continuing to do his regular beach laps in the chilly Hauraki Gulf in front of his house at Narrow Neck, Auckland.

Nicholas Tarling died in the water on 13 May aged 86, continuing to do his regular beach laps in the chilly Hauraki Gulf in front of his house at Narrow Neck, Auckland.

It was a perfect exit for a superb lecturer and masterful comic actor. Thus we lost the most prolific Southeast Asian historian of this or any age, a pioneer of the subdiscipline Down Under.

He was an improbable recruit for this leading role. His undergraduate loves at Cambridge were first English literature and then English history. Only his mentor JH Plumb convinced him to do his work on the smaller colonies, where jobs might be easier to come by. He never left England for his dissertation, deploying the British records like no other for what became the first book on British Policy in the Malay Peninsula and Archipelago. It was an area of which he would become the complete master, contributing scores of books on every corner of the region.

In 1957, having never travelled further than Paris, he accepted a job at Queensland University. John Bastin had pioneered this first antipodean position in Southeast Asian history two years earlier, and had suggested that Nick replace him as he moved to the Australian National University.

Bastin warned him he would find Australia and especially Queensland a cultural wasteland, but he flourished as he never had in Cambridge. He found that in Brisbane, as later in Auckland, he could become a Renaissance man, contributing to the arts, the stage, public policy and administration. For an essentially shy man, the theatre appeared to free him to play character and comic roles. He later tallied 140 roles in his two-volume memoir, starting in Brisbane but blossoming in Auckland.

Challenge of Asia

The move to Auckland came in 1965, encouraged by Keith Sinclair to pioneer the subject in a second country. This was the expansive 60s and 70s, as baby boomers flocked to university and history departments responded to the challenge of Asia as the new frontier.

As Nick modestly noted in 2007: ‘Looking back on my life, I concluded that one of its good fortunes was that it coincided with a great expansion in Southeast Asian historiography, in quantity, range, and sophistication, and I had enjoyed trying to be part of it.’

Despite his astonishingly full life and legendary writing output, he endured and mastered the infighting and endless committee work that demoralises most scholars

So successful was the new field that first Michael Stenson, then Leonard and Barbara Andaya, were added to the Auckland strength. Nobody thought it surprising that Nick would initiate and guide The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, published in 1992. He had already written a number of books himself that covered the whole Southeast Asian region, suitable guides for study. The Cambridge History, resolutely dedicating each thematic chapter to the region as a whole, was a remarkable step forward in legitimating Southeast Asian history as a field of study, and the Antipodes as a leader in the field.

Personally quiet but disciplined, he was an exceptionally able administrator and institution-builder. Despite his astonishingly full life and legendary writing output, he endured and mastered the infighting and endless committee work that demoralises most scholars. He fought constant battles for the autonomy and academic governance of the universities, for due resources for the Humanities, and for the Arts in society at large.

Indispensable presence

At Auckland he rose quickly to full professor, dean, deputy vice-chancellor and often acting vice-chancellor, and was the indispensable Auckland presence on national committees. His skills were also deployed as chairman of the Northern Arts Council and a founder of Auckland’s professional Mercury Theatre.

He was a frequent broadcaster on opera and the arts. For some time president of the Association of University Teachers of New Zealand, he led its pioneering delegation to China in 1977. He was tempted by the occasional deputy vice-chancellor or vice-chancellor role in Australia, but pulled back, heeding the advice of his wise friend Olive: ‘I quite honestly think that (a) you’d make an excellent V-C, and (b) you’d hate it.’

Auckland would remain a strong centre for the study of Southeast Asia until his retirement in 1997. He ensured that Asia was given its due as Auckland University and the whole New Zealand university system matured and expanded manyfold.

Regionally he became a fixture ever since the first conference on Southeast Asian History, convened by Ken Tregonning in Singapore in 1961. This was the moment that gave birth to both the first Journal of Southeast Asian History (later JSEAS) and the International Association of Historians of Asia (IAHA).

The 1971 Orientalists’ Conference in Canberra stimulated attempts to form an Asian Studies Association Down Under, but the politics of that proved difficult. Eventually Nick showed the way by establishing a New Zealand body, NZASIAN, which took somewhat unorthodox shape under his guidance at its founding Auckland conference in 1974.

He was not only first president, indispensable patron as dean of the country’s largest Arts faculty, but also factotum, writing most of the entries in its newsletter. When the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) got organised two years later, it was easily agreed with Nick that it would hold its conferences in alternate years to NZASIAN.

At the conferences that followed of IAHA and ASAA he was a reliable fixture and a voice of experience and moderation. Quietly he would rise in the concluding session to give a droll review of where we had been. As he diarised after the 1994 Tokyo IAHA: ‘I gave my “funny” speech. Almost a tradition. I hope I did not overdo it. Tony said I stole the show.’

Although well behind his Australian counterparts in experiencing the region first-hand (first visiting at 30), he warmed to it and gave back generously in the later stages of his life. In 1997 he taught for a semester in Brunei.

Having long supported the field in New Zealand, he has since 2009 supported younger Southeast Asia scholars. A trust fund supports the biennial Nicholas Tarling Conferences for younger regional historians, of which the fifth will convene this year in Bangkok. Above all it is his phenomenal output of books that will endure, documenting with meticulous care the political evolution of Southeast Asia since 1780, from the viewpoint of its dominant power. Counting them is no easy matter, when many post-retirement years produced two or three.

An exhibition in his honour in 2015 was able to display ‘at least’ 50 books. Some mention 70, The single-authored ones are over 40. He did not waste time or lose readers over postmodern introspection. Judiciously and meticulously, he told a story.

Featured image

At the first ASAA conference, Melbourne University, May 1976: from left to right: Professor Damodar Singhall (Queensland), Professor John Legge (Monash), Dr Anthony Reid (ANU) and Professor Nicholas Tarling (New Zealand)