Young people in the Philippines are reawakening to their historical role of initiating social and political change, Michael Henry Yusingco believes.

Returning home recently to the Philippines to give a lecture on constitutional rights to a political science class at Ateneo de Manila University, I found myself, two days after the lecture, again with students from the class—but this time with thousands more, participating in a protest.

The protest was taking place beside a main road outside the campus, Katipunan Avenue, named after the revolutionary organisation that led the uprising against Spain in 1896.

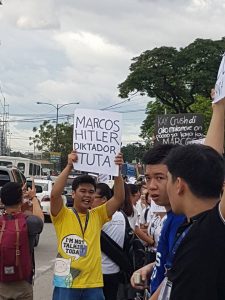

We were there in the hot afternoon sun to voice our indignation over the burial of dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng Bayani (Resting Place for Heroes). His body had lain in a mausoleum in his hometown, north of Manila, for the past 27 years.

Last July President Rodrigo Duterte made good on his campaign promise to allow Marcos to be interred in the Libingan ng Bayani, ordering his secretary of national defence to organise preparations for the burial.

The announcement provoked outrage, particularly from victims of state atrocities during Marcos’ Martial Law rule, and several petitions were filed in the Supreme Court to stop the planned burial proceeding.

On 10 November, the court dismissed the petitions, clearing the way for the government to proceed with the burial. Under the rules of the court, however, the petitioners had 15 days to file a motion for reconsideration. But, even before the lapse of this period, the Marcos family, with cloak-and-dagger planning, went ahead with the burial of their patriarch on 18 November.

Outrage

The outrage shown by Filipino youths over the burial was a revelation to me. My generation—Gen X—has always complained that millennials don’t care much about the dark days of Martial Law and the Marcos dictatorship. We have always felt that we alone bear the scars of the Marcos era and that those who followed us had a profound disconnect from this period of Philippine history.

But at the rally that day I saw university students, who are often labelled as timid and even apathetic when it comes to political action, shouting as loudly as they could amid the exhaust smoke of passing traffic and in the heat of the noonday sun, ‘Marcos diktador! Hindi bayani!’ [Marcos dictator! Not a hero!].

The protest continued through the night, with students from others schools gathering at the People Power Monument at the heart of Metro Manila. Other student rallies were also held in other parts of the country, and even bigger demonstrations followed over the next week.

Political commentator and dean of the Far Eastern University Institute of Law, Mel Sta. Maria, described the protests as ’an awakening rooted not in whim and caprice but in the lessons of a dark period in our history’, and believes they may signal the start of a new people’s movement in the Philippines. He could be right.

The president of Ateneo de Manila University, Father Jose Ramon Villarin, told the media that university administrators had not encouraged students to attend the rally. On the contrary, he said, the students had led him—a sign of a growing passion among Filipino youths to be actively engaged in national political issues.

Young Filipinos have always been in the thick of fights for freedom and democracy. Significant numbers of them, such as Gregorio del Pilar, known as the Boy General, were involved in the Katipunan-led revolution. During the Second World War, a famous band of Filipino youths, known as the Hunters ROTC, fought in the guerrilla war against the Japanese occupying force.

With their energy and enthusiasm for asserting their political rights, young Filipinos have a critical role to play in their country’s future

Students were also at the forefront of mass actions, known as the First Quarter Storm, against the Marcos dictatorship in the early 1970s. This marked the start of a long political struggle that culminated in the ouster of Marcos by people power in February 1986.

Manifesto

Late last year youth leaders from different parts of the country presented Congress with an audacious manifesto demanding legislation to end the dominance of political dynasties in government. Although such legislation has yet to be passed, the initiative led to the inclusion of an anti-political dynasty provision in a new law governing the election of local youth leaders.

Young Filipinos comprise a significant segment of the Philippine electorate. With their energy and enthusiasm for asserting their political rights, they have a critical role to play in their country’s future.

The most recent protests demonstrate that an educated, engaged and social media-savvy youth sector can enliven public discourse in the Philippines and, perhaps, force through the political reforms the country so desperately needs.

With an unorthodox and temperamental president in office, these are interesting times for democracy in the Philippines.

Featured image

Students protest the burial of dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng Bayani (Resting Place for Heroes). Photo: Michael Henry Yusingco