This post is based on a recent article published in the Asian Studies Review. The article can be read here and is currently available open access to all readers.

In the rapidly changing and ever-expanding cities of Hanoi and Yogyakarta, the spaces children roam have been steadily shrinking. Across three generations in each city, the playful wanderings of childhood have been redrawn—shrinking from lakes and rice fields to shopping malls and front yards. While Vietnam and Indonesia differ in political systems and planning regimes, our research reveals startlingly similar trajectories in the transformation of children’s urban geographies: mobility is narrowing, play is increasingly structured, and the community ties that once wove together everyday childhoods are often diminishing.

Drawing on 22 three-generation family case studies—10 in Hanoi, Vietnam, and 12 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia—this research uses narrative mapping to chart how urban childhoods have changed since the 1940s. Each family participated in individual interviews, photo elicitation, and family focus group discussions that culminated in detailed maps of three generations’ childhood mobility zones. The resulting narrative maps do more than illustrate who played where—they reveal the subtle, intimate changes of everyday urban life for children in two of Southeast Asia’s rapidly changing cities.

Childhood in the city: from unstructured play to supervised stillness

The spatial freedom of childhood has long been tied to children’s ability to explore their neighbourhoods—spaces that form the backdrop of memories, friendships, and independence. For grandparents in both Hanoi and Yogyakarta, this meant open-ended, unstructured play in rice fields, lakes, or alleyways. Children ventured out unsupervised, learning through risk, invention, and encounter. In contrast, their grandchildren’s play zones are small, often indoors, and closely monitored by adults. In many cases, movement beyond the front gate requires an escort or a ride-hailing app.

In Hanoi, grandparents remembered wandering from busy trading alleys to peaceful lakes like Hoàn Kiếm, visiting temples, markets, and friends’ homes without fear. “We went out all day and just came back at night,” one woman recalled. In her youth, neighbours watched out for one another’s children, and parents didn’t hover.

In Yogyakarta, grandfathers recalled wading in rivers, climbing trees, and roaming far beyond their compounds. One described the river as his “free swimming pool,” while another recounted fishing, playing football in empty fields, and exploring the ruins of colonial buildings turned playgrounds.

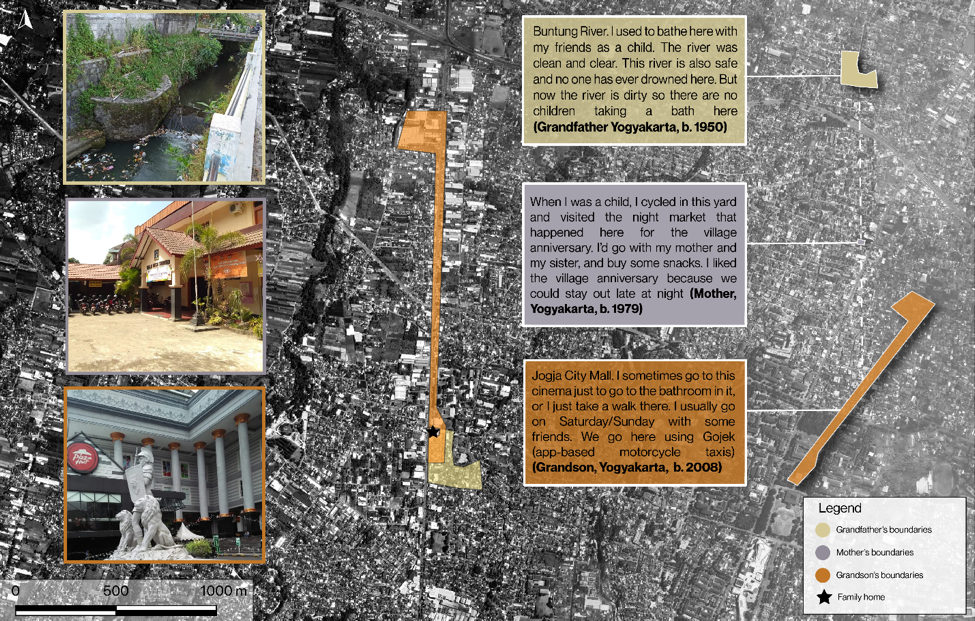

These recollections sharply contrast with those of the youngest generation. In both cities, today’s children are more likely to play indoors, their movements confined to a tight radius around their homes. While some visit malls or city squares, these outings are often accompanied by adults or occur within specific, heavily controlled boundaries. In one case in Yogyakarta, a 14-year-old boy’s longest independent journey was a straight line from his home to a shopping mall—hardly a network of childhood discovery (Figure 1).

Figure 1. From the house to the mall and home again for a grandson in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Why are children’s spaces shrinking?

Three primary forces emerged as drivers of this contraction in childhood geographies: rapid urbanisation, shifting parenting norms, and socio-political changes in public space.

In both cities, the urban fabric itself has changed dramatically. Hanoi has sprawled outward, its urban master plan promoting high-rise developments and expanded road networks at the expense of informal play areas. Since 2008, the city’s territory has doubled, but new developments often favour private over public space. Pollution and traffic have also become major deterrents to outdoor play.

Yogyakarta, though governed through more decentralised processes, has followed a similar arc. Traditional neighbourhoods have given way to commercial zones and congested streets. Older participants lamented the disappearance of shared parks and the encroachment of fences, walls, and private security.

Equally important is the shift in how childhood is imagined and managed. Across both cities, parents today express heightened concerns over safety—fears of traffic, crime, and “social evils” (a politicised term used in Vietnam to encompass everything from drug use to unsupervised roaming youth). In both Hanoi and Yogyakarta, parents described a cityscape too dangerous for children to navigate alone. Structured activities, often indoors or behind school gates, have replaced spontaneous play in the street, lake or riverside, or park.

Meanwhile, intensified academic pressure and the growing influence of digital devices mean children are spending more time inside, tethered to schedules and screens. A father in Yogyakarta captured this anxiety bluntly: “Children today are contaminated with technology.”

Diverging paths, converging patterns

At first glance, one might expect political differences to lead to divergent urban experiences. After all, Hanoi is the capital of a one-party socialist state, while Yogyakarta operates within Indonesia’s post-Suharto democracy, with its decentralised planning and unique regional governance under a hereditary Sultan.

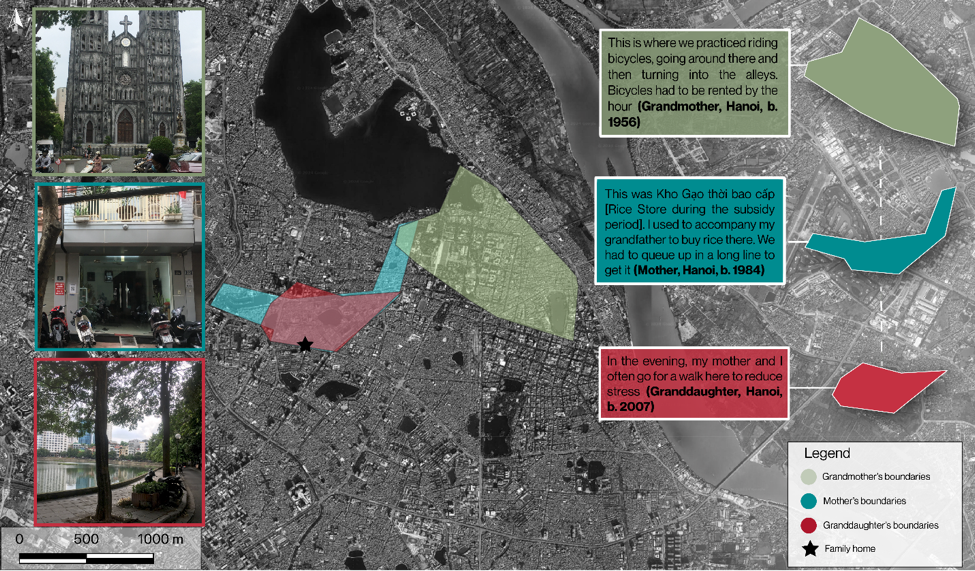

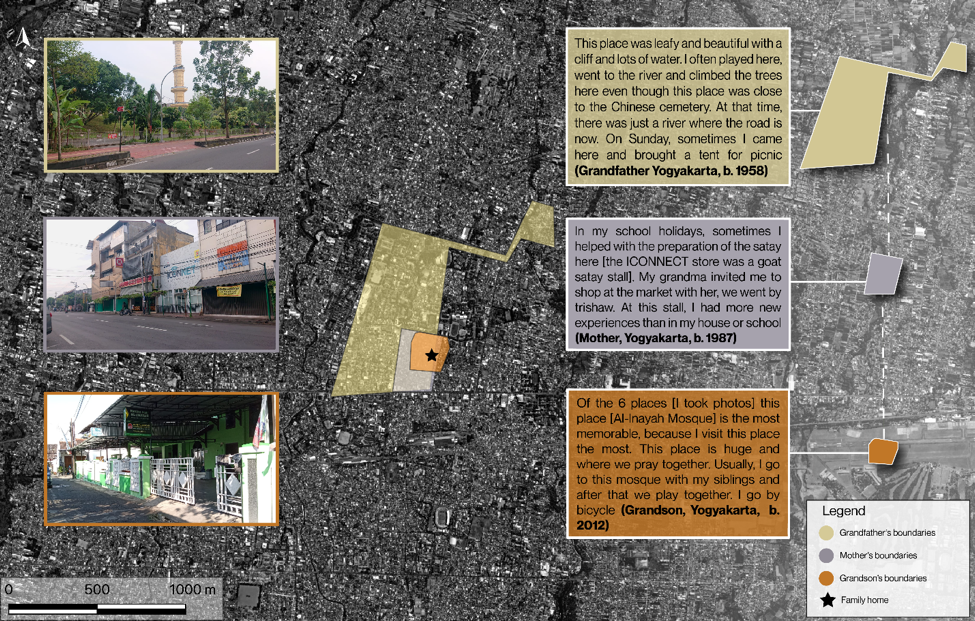

Yet despite these differences, our maps show strikingly similar spatial patterns. In both cities, the majority of families revealed a contraction of children’s play and mobility zones over the generations. In Hanoi, eight out of ten families saw a reduction in spatial scope from grandparents to grandchildren (Figure 2). In Yogyakarta, seven out of twelve did (Figure 3). And where expansions did occur—typically in the second generation—they were often modest or reversed again in the third.

This convergence points to a broader regional trajectory shaped less by political ideology and more by neoliberal urbanism, consumer culture, and shifting notions of parenting. The mall, in particular, emerged as a key play site in both cities: clean, surveilled, commercial. In several cases, the only place children could roam independently was the shopping centre—a privatised substitute for the street.

Figure 2. A common story of shrinking childhood boundaries across generations, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Figure 3. Typically shrinking neighbourhoods of play for children in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

What kind of city do we want for our children?

The contraction of children’s urban geographies has real consequences for children’s health, creativity, and sense of community. Decreased physical activity, less exposure to nature, and limited peer interaction have all been linked to declining mental and physical well-being in the academic literature.

Our findings suggest that reimagining child-friendly cities will require more than just installing playgrounds. It demands structural change—reducing traffic, reclaiming public space, and challenging narratives of fear. It also means listening to children themselves. In our interviews, children often longed for the very freedoms their parents and grandparents once took for granted.

As Southeast Asian cities continue to expand, the question is not just how we build, but for whom. Will we prioritise speed, consumption, and surveillance? Or can we carve out spaces for exploration, joy, and community?

Through narrative mapping, we have traced not only the areas children once roamed and played in, but also the socio-political forces that now shape their movements. In doing so, we hope to spark broader conversations about what it means to grow up in a Southeast Asian city—and how we might imagine more expansive, inclusive futures for the youngest among us.

This post is based on a recent article published in the Asian Studies Review. The article can be read here and is currently available open access to all readers. See here for more on the narrative mapping of these and other cities involved in this project.