A new book examines early nineteenth century Balinese society through the eyes of one of the island’s earliest ethnographers

On 20 March 1828, the merchant brig Josephine dropped anchor at Kuta, off the southern Balinese coast. Among the dozen or so disembarking passengers was the newly appointed civil administrator to the Badung court, Pierre Dubois. For the next three and a half years, Dubois lived at Kuta, where his only official responsibility was to recruit Balinese soldiers to serve in the Java War.

Born around 1776 in the village of Mouscron in the present-day Belgian province of Hainaut, Dubois served in Napoleon’s armies in Germany, Austria and Russia. After the French defeat, he was one of the thousands of disaffected and unemployed men who signed up for military service in the Dutch East and West Indies. Within a year of arriving in Batavia (Jakarta), on 28 December 1817, he had left the army and moved to Krawang, where he entered the colonial civil service.

Dubois’ administrative career was unremarkable, but he must have impressed his superiors, for in January 1828 he was promoted to his new post in Bali. A military recruitment post had already been in operation at Kuta for over a year when Dubois arrived. The decision to replace it with a civilian operation was intended to appease local Balinese concerns about the threat of a Dutch takeover of their island.

Political intrigue

Dubois had orders not to involve himself in local affairs, but he quickly discovered that recruitment was no simple transaction and found himself embroiled in political intrigue. His official reports to the Resident of Besuki and Banyuwangi in 1828 document hair-raising tales of rivalry, espionage, conspiracy and murder. His royal patron, Gusti Ngurah Made Pamecutan, was the most powerful of the triumvirate of princes ruling in Badung in the late 1820s. He was the leader of the Denpasar House, the junior branch of the Pamecutan dynasty, and owed formal allegiance to his cousin, Gusti Ngurah Gede Pamecutan.

Military success had brought Made Pamecutan to prominence and power. By forging a close alliance with the Dutch authorities, he hoped to extend his wealth and prestige. But he reckoned without the jealousies and self-interest of his rivals. An orchestrated campaign against the Dutch presence in Bali, spearheaded by Gusti Putu Agung, Gede Pamecutan’s elderly mother and the real power behind the throne, eventually forced Dubois to flee to Java, after Made Pamecutan died suddenly on 31 October 1828, allegedly poisoned by his Pamecutan rivals.

Dubois returned to Bali in February 1829 at the request of the new Badung ruling faction and continued enlisting men for the colonial army. As the Java War came to an end, the demand for soldiers dropped and agricultural labourers were recruited instead, but this proved no more successful than the military recruitment. In May 1831, Dubois was recalled and assigned to an administrative role in the Residency office in Besuki.

I refrained altogether from the least critical remark, because someone might have said: ‘But Sir, what are you doing here if not selling slaves?’ And indeed my recruitment was nothing else.

Dubois to Resident of Besuki and Banyuwangi, 15 March 1835

Throughout the Dutch East India Company period, the local princes and the Dutch had mutually benefited from the lucrative trade in slaves. The anti-slavery movement of the early nineteenth century had curtailed the trade in humans and the Dutch authorities were at great pains to insist that all soldiers would be volunteers. Yet no free Balinese would willingly leave the island.

The pressing demand for recruits during the Java War meant that expediency overrode ethical considerations. The ‘voluntary’ recruits, bound in chains to bamboo poles and delivered to the recruitment post by local Bugis and Chinese traders, were predominantly debt slaves or criminals sold by their lords. Dubois himself was in no doubt about the nature of recruitment in Bali, but later remarked that he had dared not speak out against it. The closure of the Kuta post in mid-1831 marked the end of over two centuries of Dutch involvement in the slave trade in the Indonesian archipelago.

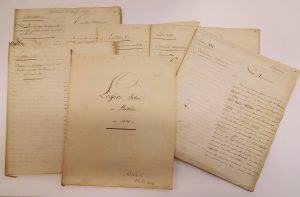

During his time in Bali, Dubois also became engaged in a project of a very different nature. In June 1829, the Secretary of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences wrote to him asking him to comment on a report on Bali that had been prepared by HA van den Broek, the former Dutch commissioner to the island in 1817–18. Dubois agreed, but finding Van den Broek’s account riddled with errors, resolved to write his own account of Bali. The result was his Sketch of Bali in 1830 (Légère Idée de Balie en 1830), a series of personal letters to an anonymous, and undoubtedly fictitious, correspondent, in which he documented Balinese society, politics, religion and culture in the early nineteenth century.

Dubois’ text is an ethnographic tour de force of some 130,000 words in three different manuscripts, written in his native French. Other commentators from the time of the first Dutch voyage to the Indies in 1597 had described some features of the island and its people, but Dubois was the first to stay long enough to provide an accurate and nuanced account based on long residence and careful observation.

An ethnographic pioneer, his toolkit contained all the standard techniques that would later shape the discipline of modern anthropology: long-term fieldwork, participant observation, mastery of local languages, interviews with a wide range of informants and extensive note-taking for later reflective analysis.

Accuracy was his guiding light, and Dubois refrained from describing what he had not seen himself. In his vivid descriptions, we can still recognise the Balinese physical and cultural landscape of the twenty-first century: vistas of rice fields, temple and palace architecture, the colour and pageantry of religious rituals and ceremonies. Even the rather idiosyncratic map that accompanied his detailed description of the urban and rural landscapes around Kuta and Denpasar where he lived, was, as he rightfully claimed, an improvement on earlier maps, for Bali’s southern region had barely been surveyed at this time.

Equally vivid and rich is his depiction of Bali’s social institutions: its system of governance, its caste restrictions and social boundaries, its religious beliefs and practices, some now lost or forgotten.

His is the first eyewitness account of the lives of ordinary Balinese with whom he interacted on a daily basis, and of the Badung court with its lavish lifestyle and institutionalised prostitution (which rather shocked his sensibilities). Most striking of all is his intimate portrait of the inner court, and of the women who were to sacrifice themselves on Gede Pamecutan’s funeral pyre in April 1829.

I have never ceased to nourish the desire to fulfil to the best of my ability … the promise that I made in 1829 to offer some day to the Society of Sciences and Arts in Batavia a grain of Balinese sand.

Dubois Sketch of Bali in 1830 Letter I:20

Dubois left Bali in mid-1831 and never returned. Over the next decade he continued working on his project, writing and revising a series of more than twenty letters about Bali. Unsurprisingly, like most Europeans who encountered new societies in this era, Dubois, who was much influenced by values of the late French Enlightenment and especially the work of Voltaire, shows a contradictory mix of empathy for and revulsion towards the Balinese Other he describes.

Above all, this fair, slight (he was 1.7 metres), blue-eyed European who forged a friendship with an ambitious Balinese prince depicts the human face of colonial encounter in the early nineteenth century. Dubois was still working on his final manuscript when he died on 3 May 1838 at the age of sixty-one leaving as his legacy a remarkable, richly detailed first-hand account of Bali.

Featured image

The World Turtle (Badawang Nala). Dubois wrote (Letter VIII:12-13)): It is built of open-work bamboo, but it is comprised of eleven tiers … Each of its four sides is elaborately decorated. There is a representation of an enormous turtle underneath the pyramidal contraption gives the impression it is carrying it along on its journey, but it is the shoulders of more than four hundred men that perform this task.