After a bold start, there are signs India’s prime minister Narendra Modi may be taking a more cautious approach to reform

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, was swept to a massive electoral victory in May 2014. In a very presidential-style campaign, Modi promised parivartan (change) and vikas (development).

Modi held up his achievements as chief minister in Gujarat state—uninterrupted electricity supply, excellent roads, swift approvals of investment proposals—as examples of what he would do as prime minister. And there were other sweeping promises. Billions of rupees of ‘black money’ held overseas by Indians would be recovered, inflation would be reined in, more would be spent on education, and so on. With a crushing majority in the Lok Sabha, the lower house of the Indian parliament, there were high expectations that major reforms would quickly become law, the pace of economic growth would pick up sharply and that unemployment would fall dramatically.

Modi’s first months in office seemed to indicate that the pace of reform would be rapid and widespread. Modi announced many striking initiatives. A few brief examples will have to suffice for a large number of bold announcements.

On his many overseas trips, Modi referred frequently to his Make in India program, intended to make India a manufacturing hub by cutting red tape, easing restrictions on foreign investment and revising labour laws. Another was Swachh Bharat (Clean India), which aims to eliminate all open-air defecation in the nation and manual scavenging by Gandhi’s 150th birthday in 2019.

Another of its ambitious targets is to build 110 million toilets in five years, a rate which will require building one toilet per second. Yet another hugely ambitious announcement was Namami Ganga (Obeisance to the Ganges), which promises to clean up the River Ganges by 2019.

Two major urban projects were also announced: the 100 Smart Cities scheme and the Atul Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT). The former is a competitive program that will focus on water supply, sanitation and waste, transport, affordable housing, power, IT connection, e-governance, health, education, security and management. The second scheme (named after a former BJP prime minister; the name replaces a Congress scheme named after Nehru) has roughly similar objectives and is aimed at India’s smaller cities.

Mixed assessments

A few months after the passing of Modi’s second year in office in May 2016, assessments of what had been achieved were mixed. On the whole, the economy appeared to be in relatively good condition, especially when compared to other major world economies. Against that, there had not been a surge in additional jobs which many who had supported the BJP might have hoped for.

On the plus side, a huge number of ordinary Indians were given access to bank accounts into which government payments would be made directly. Several regulatory reforms in bankruptcy and real estate had also been passed. But progress on a number of other high profile programs had not progressed to the point that their likelihood of success could be judged.

If Narendra Modi has made a much slower start to making significant economic reforms than many of his supporters had hoped, has he begun as he means to go on, or will we see a baDa kadam (a big step) once all the ground has been prepared? One possible keyhole through which we can peep is that of personality. Is Narendra Modi’s personality that of the typical reformer?

To answer that question I have adopted—in an admittedly crude and impressionistic way—the methodology to examine presidential personality employed by Steven Rubenzer and Thomas Faschingbauer in their 2004 study of Personality, Character, and Leadership in the White House.

Rubenzer and Faschingbauer utilised the Revised NEO Personality Inventory to assess forty-three US presidents on the ‘big five’ dimensions of personality: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Lacking both the resources, wide college of collaborating scholars and time available to Rubenzer and Faschingbauer, I have made my preliminary assessment by relying on the comments and assessments of other observers and commentators.

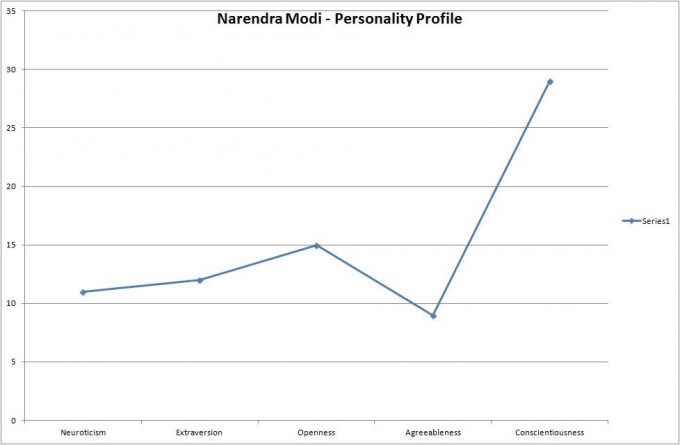

The overall results of my rapid assessment are given in Figure 1.

Modi has relatively low scores on neuroticism, extraversion, openness and agreeableness. On conscientiousness—which includes competence, order, dutifulness, achievement (high aspiration), self-discipline and deliberation—he scores very high. In these traits Modi most resembles several US presidents who Rubenzer and Faschingbauer classify as ‘dominators’.

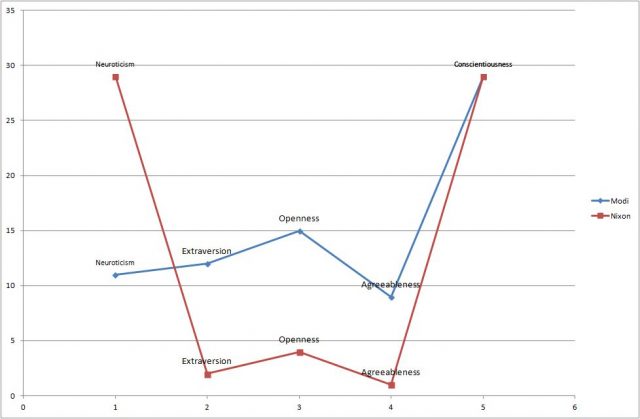

US dominators had a reputation of ‘being someone to be reckoned with’; most were ‘very disagreeable’, not open to experience and low on agreeableness. They varied widely on extraversion, were quite high on neuroticism and conscientiousness. Of the three US dominators, Andrew Jackson, Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, Modi most resembles Nixon, save that I rank him relatively lower on neuroticism—an aspect in which Nixon was very high (Fig. 2) . Most US dominators were marked by qualities such as assertiveness (bossiness), achievement striving and low straightforwardness. These are traits associated with better than average presidents (Nixon is an anomaly).

When Rubenzer and Faschingbauer sought to correlate aspects of personality with the ratings historians have offered about how successful different presidents were, they found the more successful tended to ‘be innovative in his role as an executive’; ‘be characterised by others as a world figure’, ‘initiate new legislation and programs’. There is not a great deal to go on here as far as Narendra Modi is concerned. Can we find any clues in the presidential career of Richard Nixon?

Sidney M Milkis and Michael Nelson argue in their book, The American Presidency: Origins and Development, 1776–2011, that Nixon ‘aggressively sought to expand presidential power’, using it as ‘a lever for a broadly conservative domestic policy’.

Nixon, in this account, pursued an apparently paradoxical strategy—to return power to the states and at the same time seeking to centralise power in the White House. This involved reorganisation of traditional executive responsibilities away from departments and agencies, bringing them into a greatly expanded Executive Office of the President. This was particularly evident in foreign affairs where Nixon and Kissinger created a parallel structure which largely marginalised the State Department, until Kissinger was made Secretary of State.

Nixon reorganised the bureaucracy, moving ‘proven loyalists into the departments and agencies and then consolidat[ing] leadership of the bureaucracy into a “supercabinet” of four secretaries whose job was to implement all of the administration’s policies’. In the face of domestic resistance, Nixon pursued domestic policy objectives by executive orders, thus circumventing Congress, creating what Arthur Schlesinger, Jr, termed an ‘imperial presidency’ but also planting thereby ‘the seeds of his own disgrace and resignation’.

Making due allowances for the difference between presidential and parliamentary systems, vastly different political cultures and histories, Nixon’s strategy of centralising power so as to make government largely subservient to his authority strikes me as very much the approach that Narendra Modi has taken in the past and is likely to pursue in the future.

The analysis here suggests that the centralisation of power and authority is a much higher priority for Modi than using his huge parliamentary majority to push through major reforms. Given his past preference for working though bureaucrats handpicked for their personal loyalty to him, it seems likely that Modi’s initial year or so was focused on identifying those people and placing them in key positions.

In the remaining years of his current five-year term, Modi seems likely to proceed incrementally and pragmatically, putting most of his effort and budgetary resources into major infrastructure projects which will allow him to strengthen ties with key business partners.

The model also suggests that he will not wish to proceed quickly or extensively with privatisation of state-owned enterprises, but will rather seek to use key companies, and especially banks, to project and pursue key national interests.

This article is adapted from a paper presented to the International Convention of Asian Scholars Conference, Adelaide, 6–9 July 2015.

Featured image

Narendra Modi being sworn in as prime minister in 2014. Assessments of his performance as a reformer since then have been mixed. Photo: Wikimedia Commons