Australia has been rocked in recent months by allegations that China has been engaged in foreign influence activities in Australia. China’s rapid rise, the recent centralisation of power by President Xi Jinping, and the relatively high rates of Chinese immigration, have made some Australians feel that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is extending its influence in Australia, which may lead to the undermining of the country’s sovereignty and democratic values. Doubts have been raised about the position of Chinese immigrants and Chinese university students. Is their loyalty to Australia or to China? Are they assisting the extension of the CCP’s power into Australia?

This concern is not, in fact, altogether new in Australian history. One hundred years ago a similar situation confronted Chinese people in Australia. A large influx of Chinese migrants, the anti-Christian Boxer Rebellion in China from 1899 to 1901, and an Australian racist backlash combined to create a fear of “the Yellow Peril”. Questions were raised as to whether Chinese migrants were a threat to the country’s stability and Australia’s Christian values. These concerns culminated in the White Australia Policy that was brought in after Federation.

The policy, of course, prevented more Chinese from entering Australia. But what about those Chinese who had already migrated and settled in Australia? These Chinese Australians had long been interacting with Australian society and had to a large extent become assimilated. How did the Chinese Australians feel when Australia did not welcome Chinese immigration? How did they think about their relationship with Australia when they faced such restrictions and exclusion? Do the Chinese Australians think in the same way now as they did one hundred years ago?

Cosmopolitanism before the White Australia Policy

The end of the nineteenth century witnessed the growth of a new urban Chinese elite in Australia. They were wealthy merchants and influential leaders in the Chinese community. Many of the elite were Christian and had been educated in colonial schools. They included, for example, Quong Tart, Kong Meng Lowe, and Way Lee. Their social networks extended from the Chinese community to other parts of Australian society. They expected Australia to give Chinese residents a chance to assimilate into their society.

Since the Gold Rush in 1850s, the Chinese community had suffered discrimination and restrictions. To improve their situation the Chinese elite made great efforts to culturally assimilate the Chinese community into Australian society. On the one hand, the elite tried to use Christian theology to explain Confucianism. For instance, one leading Chinese, Way Lee, argued that that the teachings of Jesus and Confucius were the same. In this opinion, both Christianity and Confucianism inspired people to worship the “omnipotent God” and live morally. He also believed that the Chinese could convert to Christians if missionaries learnt Chinese language and used the cultural similarities.

On the other hand, elite Chinese Australians expressed their belief in the Western values of “equality” and “liberalism”, arguing that the Chinese deserved the same rights in Australia as the British and Europeans.

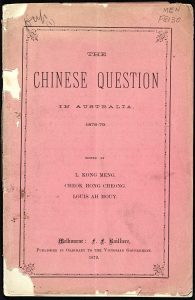

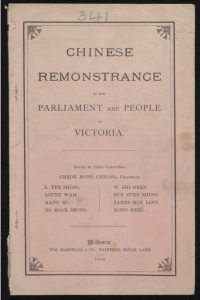

In two political booklets published in the late nineteenth century, The Chinese Question (1879) and Remonstrance to the Parliament and People of Victoria (1888), leading Chinese figures argued that Chinese residents deserved equal status in Australia because the Chinese were civilised and both Chinese and European culture valued morality.

The authors condemned the double standard on the principle of equality. They claimed that the self-evident truth that “all men are created equal” was not practised in Western countries, and that the “common human rights” of Chinese residents were frequently violated.

Rise of Chinese Nationalism

The influence of the Chinese elite’s attempt to advance the idea of cosmopolitanism was, however, limited. The Chinese Australians had to face further restrictions brought by the Immigration Restriction Act in 1901. Influenced by this policy, businesses and industries of the Chinese Australians were boycotted by white Australians. In 1903, a Royal Commission proposed legislation to restrict the activities of Chinese furniture and laundry businesses in Victoria because white Australians believed the Chinese competition influenced Australians’ interests. In 1904, the Anti-Chinese and Anti-Asiatic League was set up to boycott Chinese businesses in New South Wales.

As a result of the White Australia Policy, the ideology of the Chinese Australian elite turned from cosmopolitanism and cultural assimilation to Chinese nationalism. In Chinese-language newspapers, the elite expressed its support for a strong Chinese nation-state to guarantee the interests and survival of the Chinese “race” amidst a global struggle between different races.

They saw the rise of Japan as a positive example, demonstrating that a strong country was beneficial to its people. They warned the Chinese, both overseas and in China, that they should learn from the lessons of discrimination against Jews and Africans, whose misfortunes, they argued, were due to the fact that they were “people without countries”.

Although there were conflicts within the Chinese elite over business interests and political stance, the common idea shared by all sides was Chinese nationalism. The Chinese elite in Sydney backed a constitutional reform of the tottering Qing Dynasty, while the Melbourne elite supported the republican revolution led by Sun Yan-sen.

However, in Chinese-language newspapers published in these two cities, both of these elite groups quoted the theory of Wang Jingwei, a revolutionary leader, who emphasised that the Chinese belonged to one group, sharing common blood, language, territory, customs, religion, and culture.

Sense of Belonging of the Overseas Chinese

Over a century ago, the White Australia Policy forced elite Chinese Australians to abandon their earlier hopes of inter-ethnic “equality” and “liberalism” in Australia. They turned to an ideology of racial nationalism, believing that only by strengthening their own Chinese nation-state could their interests be protected. This result of this shift was that the Chinese elite began to manifest a clearer sense of belonging to China, rather than to Australia.

What can we learn from this history of the Chinese Australians? It is possible that a similar shift in the attitudes of the Chinese Australians could occur again today. Fears of a “silent invasion”, or of being “swamped by Asians”, or policies that might remind Chinese of the “century of national humiliation”, may increase feelings of alienation among the ethnic Chinese. Even if the target of criticism is the Chinese Communist Party rather than the Chinese people, many Chinese may still regard this as an excuse for anti-Chinese sentiment, especially given Australia’s history. The rise of a powerful China – unlike a century ago when the Qing Dynasty was close to collapse – may mean that such alienation is generated all the more easily. This may lead, once again, to a stronger sense of belonging to China among Chinese migrants to Australia.

Featured Image: Portrait of Quong and His Family. From Margaret Tart, The Life of Quong Tart or, How a Foreigner Succeeded in a British Community (Sydney: W. M. Maclardy: 1911), p. 68.