Associate Professor Stephen Epstein gave the Korean Studies Association of Australasia Regional Keynote Speech at the ASAA’s 25th Biennial Conference which was held at Curtin University from 1 to 4 July 2024. This post is a summary of the regional keynote speech given at the conference.

South Korea has long been a crucible of social ferment, its compressed modernisation producing ongoing changes with a speed and intensity that few countries have matched. The overarching theme of “Asian Futures” at the recent 25th ASAA Biennial Conference inspired me to consider life on the Korean Peninsula in the not-so-distant year of 2039; in my regional keynote “ ‘Korea’, Korean Studies and Global Futures,” I set out to be provocative and spark collective discussion of the enormous changes that we can see unfolding there in multiple spheres and what they might mean for Korean Studies as a field. Below I highlight a few of my key points, with a focus on demographic change.

Although the seriousness of the issues that South Korea will be confronting as a result of rapid fertility decline and the aging of society has been evident for some time, I remarked that only in recent months have South Korean media and public awareness treated these problems with the urgency demanded. My interest in the talk was not to explore the oft-discussed reasons for these trends or to suggest policy measures to address them but rather to consider the larger implications that they hold for Korean society and for the practice of Korean Studies as a field. Indeed, I argued that the world would do well to pay close attention to how South Korea addresses its challenges, as it is a canary in the demographic coalmine, and we are witnessing similar issues occurring in almost every developed country, albeit at a slower pace.

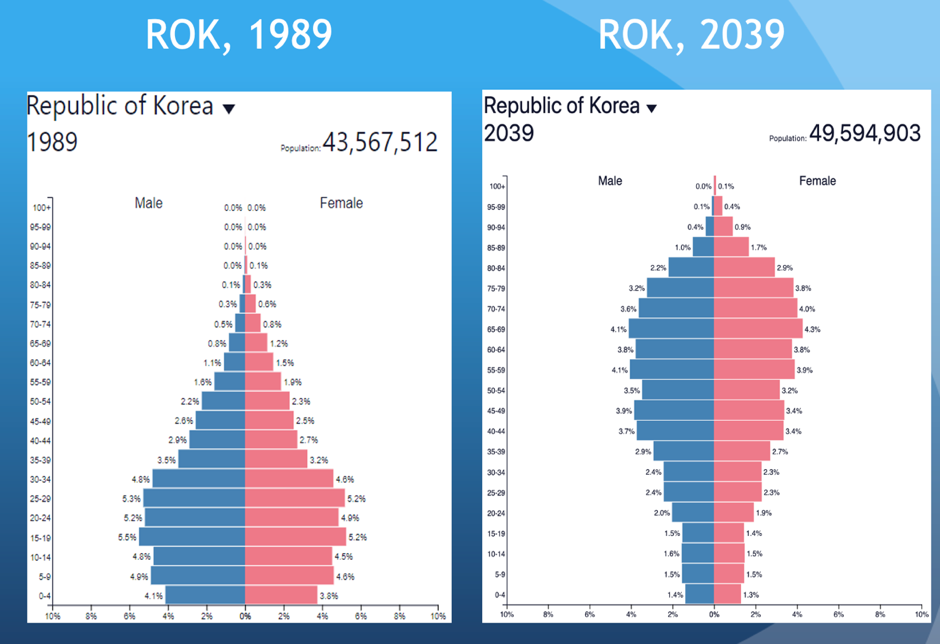

Many statistics from South Korea are mind-boggling: the total fertility rate just a decade ago in 2014 was already extremely low at 1.20, but that figure is almost 0.50 higher than the 0.72 that Statistics Korea recorded for 2023. While much about the future is opaque, demographic data does offer certainties to cling to: it seems simultaneously stupid and profound to note that every member of my audience alive in 2039 will be 15 years older than on the day the talk was delivered. Assuming consistent mortality rates, then, we already know what the population pyramid for over-15’s in Korea will be like in 2039, and it would be unrealistic to expect a spike in the fertility rate any time soon; current trends point instead towards further downward pressure (I do not expect the uptick seen in the latest quarter to continue beyond 2025).

These extraordinarily low birth rates are unlike anything the world has seen outside of wartime and natural disasters, and we can readily develop an unsettling portrait of their social and economic ramifications. A hallmark of Korean Studies in the first quarter of the 21st century has been addressing its rising presence in the world through its cultural industries and vibrant popular culture; I urged that the central topic for scholars to address in the coming quarter century should be demographic change and its impacts.

Image: PopulationPyramid.net

I asked the audience to think through the (to me, staggering) significance of the juxtaposed population pyramids above. If, as L.P. Hartley reminds us, the past is a foreign country, it is worth stating that so too is the future. South Korea is rapidly becoming Other to itself. When I first spent an extended period in South Korea at Yonsei University in 1989, a half-century prior to 2039, only one person in twenty was over 65, but that figure will have risen to one in three, and whereas almost half the population in 1989 was under 25, only one in six will be similarly youthful by 2039. Few would disagree that in 1989 South Korean society felt exceptionally dynamic and future-oriented; not long afterward, the country would take on the mantle of “Dynamic Korea” in its branding. It becomes very difficult, however, to see how such a self-conception can survive this communal turbo-aging.

These enormous shifts will have impact in a wide variety of areas, and in my discussion I considered its effect on, e.g., attitudes towards children and the rise of “no kids” zones; generational cohorts; elder poverty; and attempts to redress labour shortages through migration. I pointed out that the quotation marks around “Korea” in my title arose for two reasons: first, given that South Korea has gone from strength to strength amidst the remarkable success of its cultural industries in multiple fields (one need only think of Parasite, Han Kang, Squid Game, BTS), I raised the question of what (South) “Korea” might mean as brand and image a decade and a half from now. While it is hardly impossible for this global eminence to continue amidst a super-aged society, one might also reasonably wonder whether what I call “Special K”, the letter present in K-pop, K- drama, and K-food, etc., will carry the weight it does today as a signifier.

I also spoke of a second need for quote marks: when the term “Korea” is used in the West, it is often used unthinkingly to refer to South Korea, but there are unsettling indications that the existence of North Korea will have greater impact on this usage by 2039. Our ever more fragmented and unpredictable geopolitics make it imperative to consider how a rapidly shrinking pool of conscripts may affect the power balance on the Korean Peninsula. Will calls for female participation in the military grow? Amidst the run-up to the 2024 US presidential election, North Korea’s entrenched status as a nuclear state with powerful patrons has impinged once more on global headlines. The demographic changes I have outlined highlight that, by 2039, South Korean administrations will face an extremely difficult budgetary balancing act in weighing up military capability against providing for an aged population.

I also put forward a view from left field to stir debate: Could it be that Kim Jong Un’s abandonment of reunification as a national goal earlier this year was based on assessment that absorbing his southern neighbour may no longer be worthwhile? Far from the “bonanza” (daebak) that disgraced ex-President Park Geun-Hye envisioned in her promotion of reunification, perhaps the North Korean leader foresees that rather than taking over a vibrant economy with room for growth, he would be saddled with an administrative headache with the requirements of the Republic of Korea’s super-aged population.

Come 2039, I asked, who might be practitioners of Korean Studies, where will the field will be produced and what topics might guide it? Will we see a cooling of interest in South Korean popular culture and Korean language? South Korea’s demographic changes will almost certainly lead to mass closures of universities within the country itself, a trend already in evidence. The outlook for the local population pool for universities is grim: consider that there were 715,000 births in 1995 to supply the entering classes of a decade ago. The number of births dropped to 244,000 in 2020, which will cut the potential number of local university students to a third of its recent size by 2039.

I highlighted the unintentional black humour of a promotional campaign from Kangwon Tourism College in Taebaek, which proclaimed that it is “one step ahead of the future.” The institution closed earlier this year. One step ahead of the future, to be sure. And we should remember that when a university closes, its impacts ripple throughout the community. Kangwon Tourism College was the sole tertiary education provider in Taebaek, a former mining town with a depressed economy. Unsettlingly, such current trends also imply diminished employment prospects within Korean Studies by 2039 even as postgraduate student numbers have never been higher.

I attempted to close on a more positive note given the unsettling tenor of my talk and noted that if nothing else, Koreanists will still have plenty to research and write about. I put forth several compelling topics that have yet to receive adequate attention but are likely to demand research, including: the relationship between the developing cohort of “Gen MZ” and the elderly (and the extent to which the term Gen MZ will serve as a useful discursive construct); the impact of climate change concerns upon childbearing and migration trends within Korea as its summers become increasingly unbearable; gender and attitudes towards conscription; human and non-human interaction, ranging from pets to robots and AI chatbots as companions, counsellors and religious intermediaries; pandemic preparedness; and South Korean relations with South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

I concluded, moreover, that South Korean society has always had the capacity to produce surprises. After all, South Korea is the country that produced the “Miracle on the Han”; in 1989 no one would have predicted that it would become one of the world’s leading purveyors of popular culture by 2024. The demographic challenges that South Korea faces are immense, but the country has overcome imposing odds before.