Judge Hayato Aoki speaks to A/Professor Stacey Steele about recent developments in Japanese detention and bail processes. Judge Aoki was a Visiting Research Scholar at Melbourne Law School from June 2018 to June 2019.

SS: Judge Aoki thank you for agreeing to share your reflections about the Japanese criminal justice system. It has been a pleasure to host you at Melbourne Law School as a Visiting Research Scholar.

HA: Thank you for your hospitality. I came to Australia after being a judge in charge of criminal cases, including lay-judge trials, for three years, so I am still at the start of my career. The opportunity to research and study at the Asian Law Centre, Melbourne Law School has been invaluable.

SS: I know that you have been following Australian criminal law developments closely during your stay, but today you have kindly agreed to speak to me about recent developments in Japanese detention and bail processes.

HA: It’s my pleasure. I know that there is a lot of interest about the Japanese criminal justice system in Australia.

SS: In Japan, a person may be held up to 23 days without being charged. Could you explain how that process works please?

HA: Well, investigations are initially conducted by the police. When the police believe that there is sufficient evidence, the police will seek an arrest warrant from a judge and arrest the suspect on the basis of that warrant. The investigation authority can keep the suspect in police custody for three days before making a request to the court for the detention. After three days, a public prosecutor may apply for detention of the suspect to a court. If the court decides to order the detention of the suspect, the investigation authority can detain the suspect for up to a further 10 days. The public prosecutor can also apply for the extension of this detention period to the court for a further 10 days. After 23 days in detention, the public prosecutor must decide whether to charge the suspect or release the suspect on the 24th day.

SS: How many people are detained for the full 23 days?

HA: In 2017, 59 percent of the total number of people held in detention were held for a period of 15 to 20 days according to statistics from the Public Prosecutors Office.

SS: Some commentators criticise this period of time for detention without charge for being too long…

HA: From my perspective, the law states that a judge may detain the suspect upon the request of a public prosecutor when two tests are met. First, there must be a probable cause to suspect that the person has committed a crime. Secondly, one of the following further criteria must also be met: (1) the person has no fixed residence; (2) there is probable cause to suspect that the person may conceal or destroy evidence; or (3) the person has fled or there is probable cause to suspect that the person may flee. Further, the law provides that a judge may extend the period upon the request of the prosecutor when a judge finds that unavoidable circumstances exist. Interestingly, the cases in which judges reject a prosecutor’s request for detention are increasing.

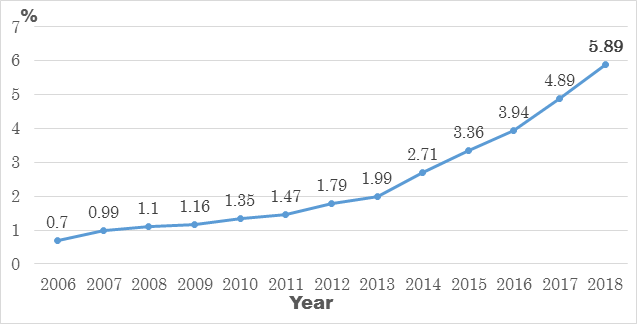

SS: Please tell us more about the increasing rates of judges dismissing prosecutor’s applications for detention.

HA: This graph shows the rate of dismissal of detention applications from 2006 to 2018. In other words, the judges decided in these cases that the prosecutor’s case did not meet the two tests that I described previously. The rate of dismissal of detention applications was 0.7% in 2006 and 5.89% in 2018 – about eight times the rate of 2006. As you can see, the dismissal rates started to increase noticeably from 2014.

SS: So, why are dismissal rates increasing? Did something change in 2014?

HA: Yes. The Supreme Court handed down a significant decision in 2014 setting out its thinking about detention. In that case, the suspect was arrested for indecently touching of a female secondary student on a train. The suspect denied the student’s allegation. The suspect was an office worker and he did not have any conviction record. The Kyoto District Court Judge dismissed the application for detention. The public prosecutor appealed and Appellate Court quashed the decision of the District Court judge and granted detention. The defence lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court quashed the appellate court’s decision and dismissed the detention application.

SS: So, in other words, the Supreme Court supported the District Court Judge’s initial decision not to detain the suspect, right?

HA: Correct. The key issue was whether there was probable cause to suspect that the suspect may conceal or destroy evidence. In this case, for example, the court had to consider whether the suspect may pressure the student to change her allegation. The Supreme Court said, “this incident happened on a crowded train in the central district of the city and there is no concrete reason to suspect that the suspect may pressure the student”. The Court found that judges should carefully examine whether there is probable cause to suspect that the suspect may conceal or destroy evidence and avoid unnecessary detention.

SS: Do you think it was likely that the suspect would try to contact the student?

HA: It’s hard to say, but I think it’s unlikely that the suspect even knew how to contact the student. The incident happened on a crowded train during the morning rush hour. Obviously, detention deprives people of their freedom and judges will try to minimise the period of detention by dismissing unnecessary applications from prosecutors.

SS: Is the lack of dismissal of detention applications linked to the lack of cases where bail is granted in Japan?

HA: The accused can only apply for bail after the accused is charged and only judges can grant bail. However, we don’t have bail hearings in Japan and judges make bail decisions based on written submissions. If bail is granted, several conditions are typically imposed and the accused must pay between A$20,000 to A$40,000 in cash.

SS: That’s a lot of money. How do people come up with so much cash in Japan to pay bail – even if bail is available?

HA: There are organisations in Japan which provide bail money support. The Bail Support Association of Japan, for example, provides bail money by supporting poor accused persons who cannot prepare bail money. Generally speaking, the family of an accused person applies to this organisation by submitting documents about the accused’s financial situation and then the organisation decides whether to provide bail money. If the organisation grants the application, the organisation provides the lawyer of the accused person with the bail money. If the accused person continues to comply with any bail conditions until judgement, the court will return the bail money to the lawyer and the lawyer will return the bail money to the organisation. If the accused person does not comply with the bail conditions up until judgement, the court will forfeit the bail money, and the family of the accused person must repay the bail money to the organisation. If the accused fails to comply with the bail conditions, bail may also be revoked. In Japan, contravention of a bail condition does not constitute an offence.

SS: I understand that there is no separate law which sets out the details for bail in Japan. Rather, the key provisions are set out in the Code of Criminal Procedure. Do those provisions give much guidance to judges?

HA: There are two main articles in the Code of Criminal Procedure. First, article 89 provides that a request for bail shall be granted, except when certain circumstances are met. Those circumstances include where the accused has allegedly committed a crime which is punishable by the death penalty, life imprisonment or a sentence of imprisonment whose minimum term of imprisonment is one year or more; the accused was previously found guilty of a crime punishable by the death penalty, life imprisonment or a sentence of imprisonment whose maximum term of imprisonment was in excess of 10 years; there is probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence or harm or threaten the victim or any other person who is deemed to have essential knowledge for the trial of the case; or the name or residence of the accused is unknown. Because many accused people fall within one of these circumstances, judges do not grant bail in those cases. The second provision dealing with bail is article 90, which allows a court to grant bail ex officio when it finds it appropriate to do so. This provision may apply to cases which fall within one of the circumstances set out in article 89. In such cases, the Court should consider the level of cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence or that the accused may flee. The court must balance those issues with disadvantages, including the accused’s health, job (finance), living and preparation for trial.

SS: The law relating to bail in Victoria has been revised recently in controversial circumstances (Bail Act 1977). Have you been following those debates?

HA: Yes, the Victorian bail law provides more detailed guidance to judges than the Japanese law. Furthermore, the Act treats children and Aboriginal persons differently and imposes mandatory considerations. I was also interested to observe that there are four different flow charts published in the legislation because of the complexity of the Act (see Bail Act s 3D). I’ve never seen a flow chart in Japanese legislation.

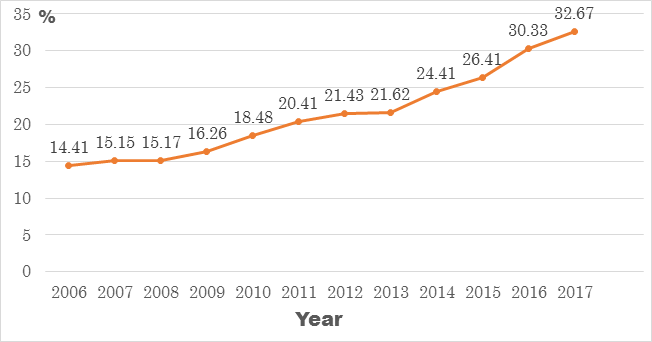

SS: How often is bail granted in Japan?

HA: This graph from [the Supreme Court] shows the rate at which Japanese courts granted bail between 2006 and 2017. The rate of granting bail has increased. The rate was 14.41% in 2006 and 32.67% in 2017 – more than a twofold increase.

SS: It looks like courts began to grant bail increasingly especially from 2009. Was that because of the introduction of the lay judge system (saiban-in seido) in Japan?

HA: Indeed, judges started to consider the disadvantages for preparing for a trial while the accused was in detention more carefully after the introduction of the lay judge system. Lay judge cases are heard over consecutive days and the accused needs to discuss the issues at trial with defence lawyers. In these cases, the court also usually tries to narrow down the issues and evidence before the trial, so there is less probable cause to suspect that the accused may conceal or destroy evidence.

SS: In Victoria, the reforms to the bail law in [2017] were driven by concerns about community safety, especially after the Bourke Street tragedy in 2017. The accused was on bail at the time of the incident. The reforms make granting bail more difficult. Is the Japanese community concerned about safety?

HA: I understand. In Japan, more accused people are receiving bail and the number of the accused who commit another offence on bail is increasing. Only 85 persons who were on bail committed another offence in 2007, but 246 persons who were on bail committed another offence in 2017. In one case, a suspect who was on bail murdered a person and injured three others by firing his gun in 2016. The court carefully considers community safety. Also remember that the accused failing to comply with the conditions of the bail does not constitute an offence in Japan. However, a person on remand loses a fundamental liberty even thought that person has not yet been sentenced.

SS: In Victoria, the adult prison population has increased partly because the remand (that is, unsentenced) population has increased. What is the impact in the increase in bail applications being granted in Japan?

HA: The adult prison population in Japan has decreased for many reasons. The key issue in Japan is not the impact of granting bail, but the significant problem of holding suspects for long periods of detention without charge. Whilst bail may become an issue in future, for now the focus is on trying to minimise the length of detention appropriately.

SS: Judge Aoki, it has been fascinating to hear your reflections on Japanese and Victorian criminal law. Do you have any final observations based on your experiences in Australia?

HA: All my experiences this year have been invaluable. My overall impression is that Japanese investigation authorities – who are administrative officers – have great power to detain a suspect for a long time before laying a charge when compared to Victoria. In recent years, however, detention rates in Japan have been decreasing partly because of judicial screening. Yet Japanese criminal justice is still controlled by administrative power rather than judicial power in comparison to Victorian criminal justice. It will be interesting to see if some of the changes which we’ve discussed today are part of a bigger shift in the Japanese criminal justice system more towards judicial power and away from administrative power in future.

SS: Judge Aoki, thank you for your time and best wishes for your future judicial career.

Featured image from Marco Verch on Flickr.