An Australian ballet teacher’s love of Indian dance helped bring two cultures together, writes AMIT SARWAL.

In the 19th century, during the British Raj, India attracted many curious and enthusiastic Australian travellers. Australians had been attracted to Indian curios, artworks, colourful clothes, and paintings of grand Indian palaces and bazaars; and the great Intercolonial Exhibition of Australia, held in Melbourne, 1866–67, had evinced the wide popularity of Indian nautch girls.

In the early 20th century, Australians were entertained by foreign dance troupes and companies performing full-length ballets, and a vulgarised form of Hindu dance. By contrast, Indian classical dance, as it has come to be known, was virtually unknown and unseen in Australia.

Louise Lightfoot (1902–79) (pictured), a trained architect and a ballet teacher, known in Australia for promoting a fusion of classical ballet and Indian dance at the Lightfoot–Burlakov school—the First Australian Ballet Company—was soon going to change this with her Indian–Australian cultural collaborations.

Louise Lightfoot (1902–79) (pictured), a trained architect and a ballet teacher, known in Australia for promoting a fusion of classical ballet and Indian dance at the Lightfoot–Burlakov school—the First Australian Ballet Company—was soon going to change this with her Indian–Australian cultural collaborations.

Encouraged by Marion Walter Griffin to take up dancing as a profession, and inspired by experimentation with various Western and Indian dance forms by her contemporaries—Anna Pavlova, Uday Shankar, Jean Erdman, Martha Graham, Ruth St Denis, Esther Luella Sherman (Ragini Devi), Sol Hurok, and La Meri—Lightfoot thought of exercising a similarly enlivening effect upon dance in Australia.

In 1937, she visited London and Paris with Burlakov to learn more about emerging dance styles and to secure the rights to perform a number of new ballets in Australia. Returning from Europe, she broke her journey in India. When she arrived in Bombay (Mumbai), she instantly ‘fell under the spell of India.’ The following year, in order to bring more appropriateness and authenticity to her own style of Indian classical dance, and to present her experimental dance in a vivid and hitherto unrevealed form and style, Lightfoot discontinued her partnership with Burlakov and travelled to Kalamandalam on the Malabar Coast.

For the next five years she lived in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, exposing herself to the techniques of the sacred dance styles, Kathakali and Bharata Natyam, while teaching classical ballet to children of the British Raj. More significantly, she became a great proponent of Indian dance troupes and soloists, organising tours in South India and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). At Kalamandalam, Lightfoot immersed herself in Kathakali. She was so thrilled by the whole experience of learning this dance form and its accompaniments—poetry, song, acting and dance—that she wanted others to share her enthusiasm, appealing to the British in India to appreciate Indian dance, and to Indian parents to allow their sons and daughters to dance.

As an impresario, Lightfoot arranged many international performance tours, including to Australia in 1952, for Ananda Shivaram, the renowned exponent of Kathakali, and singer Janaki Devi. She also worked with the filmmaker K. Subramanyam in Madras (Chennai) and published her ‘perspective’ pieces widely in the Indian press. In recognition of her support of Kathakali, Vallathol Narayana Menon—Shivaram’s mentor and the founder of the university for art and culture, Kerala Kalamandalam—bestowed on Lightfoot the affectionate title ‘Australian mother of Kathakali.’

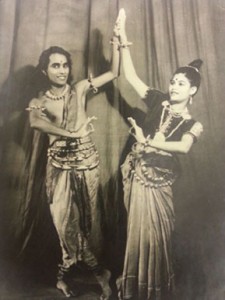

Ananda Shivaram (pictured with Janaki Devi) was one of the first Indian artists to tour the then ‘race-prejudiced Australia’ in 1947 with Louise Lightfoot. The Australian media overwhelmingly described him as an ‘exotic Hindu temple dancer’ and his visit was labelled as a unique and rare opportunity from ‘the most expressive artist’ of India. In Australia, Shivaram was celebrated as a visiting cultural ambassador.

Ananda Shivaram (pictured with Janaki Devi) was one of the first Indian artists to tour the then ‘race-prejudiced Australia’ in 1947 with Louise Lightfoot. The Australian media overwhelmingly described him as an ‘exotic Hindu temple dancer’ and his visit was labelled as a unique and rare opportunity from ‘the most expressive artist’ of India. In Australia, Shivaram was celebrated as a visiting cultural ambassador.

Lightfoot was also interested in learning the other traditional dance forms of India, especially the folk dances of Manipur. She toured internationally for four years (1947–51) with Shivaram, demonstrating Kathakali dance, and when that association ended, she sailed to Bombay to meet Rajkumar Priyagopal Singh, who had impressed her with his work in Jagoi—a form of Manipuri dance.

A distinguished member of the first family of Manipur, Priyagopal Singh had performed in major dance centres of India, Delhi, Calcutta and Bombay, but was more eager to establish himself as a guru in the international dance arena. In 1951, he and drummer Lakshman Singh became the first Manipuri dancers to tour Australia, with Lightfoot as their stage manager and artistic director. With Lightfoot’s help, they de-provincialised and popularised Manipuri dance in the international dance circuit and paved the way for other Manipuri dancers in Australia.

From late 1951, Lightfoot and Shivaram established an Indian dance school in San Francisco and spent several years touring the United States. In 1957, she was introduced to an outstanding young dancer, Ibetombi Devi, who had performed for India’s first prime minister Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru and other important national and international dignitaries.

For her next cultural tour of Australia that same year, Lightfoot selected Devi to perform in company with Shivaram. The highlight of the tour was Ibetombi and Shivaram’s brilliant performance on 14 May 1957, titled Chitangada, broadcast on Australian Broadcasting Corporation television from Melbourne.

Great cultural significance

Lightfoot’s collaboration with Shivaram, Priyagopal, and Ibetombi gave Australian audiences more exposure to Indian dance. Their dance tours had great cultural significance and these performances, lectures and demonstrations considerably enhanced the respect of Australians for India’s intellectual heritage.

Over and above curiosity, it must have been difficult, aesthetically and artistically, for Australian audiences to understand and fully appreciate a dance form with its roots reaching back to 3000 BC. But Lightfoot’s extensive notes, commentaries, explanations and interpretation of the art of Kathakali were a valuable aid in making the complicated and historically rooted dance forms plainly understandable to audiences. Unfortunately, while Priyagopal and Ibetombi have been forgotten, it is Shivaram alone whose impact and profound impression on many others through Kathakali is acknowledged even today.

Shivaram, who moved in the social life of Australia, and charmed journalists and audiences alike, brought the two cultures closer, and stimulated a period of vitality and originality through Indian dance form.

Louise Lightfoot published one monograph, Dance-rituals of Manipur (1958), and released her recording of Manipuri songs as Ritual music of Manipur in the American Ethnic Folkways series (1960). To revive the memory of Louise Lightfoot and her passion for Kathakali, in 1997 renowned dancer and choreographer Tara Rajkumar created a dance plus dialogic performance/installation, titled Temple dreaming,in Melbourne and Delhi. And in May 2014, Mary Louise Lightfoot, niece of Louise, published an e-book, Lightfoot dancing—Part 1: an Australian-Indian affair, which is part biography, part dance history and part intergenerational memoir.

I would like to thank the Music Archives of Monash University for their kind permission to use images from Louise Lightfoot Collection and Mary Louise Lightfoot for her encouragement and additional information on Louise’s life.