The recent gains by the Kurdish-dominated party in Turkey’s national election could be a watershed moment for Turkish democracy, write DAVID TITTENSOR and TEZCAN GÜMÜŞ.

Turkey’s national election on 7 June, 2015 provided a major surprise result. While pre-election polls anticipated that the ruling Islamist Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (Justice and Development Party, AKP) would take a significant hit, the debut of a new player in the form of the Halkların Demokratik Partisi (The People’s Democratic Party, HDP) exceeded expectations.

Pre-election polls indicated that the Kurdish-dominated HDP would hover around 10 per cent of the vote, the minimum threshold needed to gain representation in the parliament. As such, the move to enter the fray as a party represented a significant gamble, particularly when one considers that HDP’s constituency historically counts for around 6 per cent of the vote.

For example, the last time the Kurds ran as a party—Demokratik Halk Partisi (the Democratic People’s Party (DEHAP)—in 2002, they failed to pass the threshold with only 6.2 per cent of the vote. Similarly, when HDP’s predecessors ran candidates as independents in 2007 and 2011 to circumvent the threshold, the results were modest with 3.8 and 5.8 per cent of the vote respectively.

As a result, the recent capture of 13 per cent, which has yielded 80 seats, is a major coup that could be a watershed moment for Turkish democracy. This upswing for the Kurds has come on the back of a more inclusive policy platform that abandoned a traditional polemic centred on ethnic politics to one that promised improving economic conditions and the rights of all Turks, in particular minority groups and the LGBTQ community, combined with a campaign targeting the AKP’s credibility and President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s divisiveness.

These moves These moves expanded the HDP’s supporter base to include progressives and many Turks from largely secular cities such as Izmir, Bursa and Antalya. The party also saw many conservative Kurds who previously voted for AKP return on account of Erdogan’s mishandling of the Kurdish crisis in Kobane during the attack on the border town by Islamic State forces.

However, the rise of the HDP as a fourth player has created a complex political landscape that requires the formation of either a coalition or minority government. AKP, despite its share of the vote having fallen by 8 per cent, still remains the dominant force, with 41 per cent that has yielded 258 seats (just 18 short of the required 276 in the 550-seat parliament) and is in the box seat to form a coalition.

In contrast, the main opposition in the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (Republican Peoples Party, CHP), obtained 132 seats with 25 per cent of the vote, while the Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (Nationalist Movement Party, MHP) took 80 seats with 16.5 per cent of the vote. Basically, the distribution is such that if the minor parties want to force the AKP out of power they will all have to band together. Yet, while there is a range of options there has been little agreement, and given the AKP’s parliamentary share, forming a government without it will be difficult.

The leader of the CHP, Kemal Kiliçdaroğlu (pictured), has all but ruled out a coalition with the AKP, stating that there is only a slight chance of such a collation forming and that partnership between AKP and MHP is ‘much more likely’. Further, having ruled out a coalition with AKP, Kiliçdaroğlu has called on both MHP and HDP to form a coalition, wherein he offered MHPs leader Devlet Bachçeli the prime ministership.

Though, Bachçeli dismissed the offer on the grounds that there were too many ‘disgraceful’ incidents that had taken place between the two parties, and that it could not form a coalition with the HDP, whom he labelled as ‘the political messenger of a terrorist organisation’ Bahçeli’s statement underlines the traditional animosity between the ultranationalism of the MHP and the pro-Kurdish HDP that makes any cooperation between them highly unlikely.

Finally, HDP chair Selahattin Demirtaş had originally ruled out a partnership with AKP, while his co-chair, Figen Yüksekdağ, has stated that the door is open and that it is the AKP that does not want to form a coalition.This standoff between the various parties leaves one of two options, either an AKP–MHP conservative–right partnership or early elections, and the situation appears to be geared towards the latter. Indeed, Bachçeli, stated that the best option for a coalition is AKP–CHP as he feels it will diffuse the deep polarisation within Turkish society, wherein MHP can function as the main opposition.

Stumbling blocks

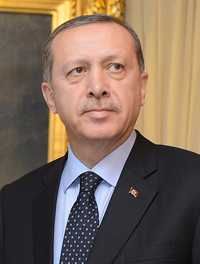

In particular, Bachçeli has cited both the corruption investigation launched against the AKP in December 2014 (allegedly instigated by the Gülen Movement) and the Kurdish peace talks as major stumbling blocks for a coalition with the AKP. Ironically, this intransigence on the part of both MHP and HDP is a boon for Erdoğan (pictured), as both have the most to lose from early elections.

As touched on earlier, the HDP got a bounce in the elections from a rights-based platform and playing up Erdoğans hyper-presidency, wherein he shirked conventional neutrality and campaigned for the AKP in his bid to achieve his two-thirds majority and change the parliamentary system to a presidential one. The situation is the same for MHP. In others words, for some the election effectively counted as a protest vote against Erdoğan’s power grab. Yet, while Erdoğan’s ambition has been thwarted, the ripple effects may only be shortlived. An early election could see these swing voters, disillusioned by the current political stalemate, return to the AKP fold for stability, which would see the party regain its previous majority and rule single-handedly.

It appears that while Erdoğan has been bruised he has not been knocked down

It appears hat while Erdoğan has been bruised he has not been knocked down and will seek to do all that he can to see AKP returned to power. This potentiality is not lost on Erdoğan, who delayed giving a mandate for the formation of a government by over a month. The delay has been interpreted as a measure to kill hope for a coalition government by fostering further dissension among the already fractious parties and give cause for a snap election.

Now that the mandate has been granted the parties have 45 days to form a coalition where a failure to do so, ideally for Erdoğan, will result in an early election. An IPSOS poll taken shortly after the 7 June result has indicated that the AKP would get a 4 per cent bump if voters had known the outcome in advance. Calculations indicate that only a 2 to 3 percent swing would be required to secure a parliamentary majority. Thus it appears that while Erdoğan has been bruised he has not been knocked down and will seek to do all that he can to see AKP returned to power, thereby avoiding his position as president being undermined.

It is entirely possible that a snap election could provide a similar result, returning everyone back to square one. Other polls have indicated that AKPcould actually lose ground. However, one thing is certain: defeat will not be ceded lightly, and the uncertainty is playing right into the hands of both the AKP and Erdoğan.

Dr David Tittensor is the research fellow to the UNESCO Chair, Cultural Diversity and Social Justice, in the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation (ADI) at Deakin University. He is also the author of The House of Service: The Gülen Movement and Islam’s Third Way (OUP, 2014).

Tezcan Gümüş is a PhD candidate at ADI and his thesis is entitled ‘Nation, Identity and the Role of Elites: Shedding light on Turkey’s Troubled Democratisation’.