Beverley Hooper is Emeritus Professor of Chinese Studies at the University of Sheffield. She was President of the ASAA in 1995-6. In this post, she reflects on Asian Studies in Australia then and now, pointing to moments of change and also of continuity.

What roles did you have on the ASAA Council? Why did you get involved?

I was a General Councillor and then China Councillor for several years before serving as ASAA President in 1995-96. My original involvement with the Council occurred when I was coopted by Elaine McKay, the ASAA’s first woman president, to fill a temporary vacancy. Attending Council meetings made me realise that there was still a great deal to be done to promote teaching and research on Asia in Australia. This was reinforced after I was appointed to head the University of Western Australia’s new Asian Studies programme in 1993. The Arts Faculty Board had approved the belated introduction of an Asian Studies degree and courses by only one vote, and this resistance did not completely disappear. I subsequently became quite active in promoting Asian Studies and in 1994 I was approached to stand for election as the next ASAA President, succeeding Colin Mackerras who had already been a prominent figure in Chinese Studies when I was a “mature age” PhD student.

What contributions did you make to the ASAA as President?

I became President during quite a “heady time” for Asian Studies: the latter part of the period (from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s) which the 2023 ASAA Report Australia’s Asian Education Imperative describes as a “boom” in Asian Studies in Australian universities (p 25). Prime Minister Paul Keating had accelerated Bob Hawke’s drive to engage more with the Asian region, accompanied by official calls for greater professional expertise on, and wider knowledge of, Asian languages and societies.

But the momentum was already declining, even before the change of government in March 1996. A lot of the ASAA’s time was spent trying to maintain government funding for programmes which were sometimes for a specified period. The Australian Awards for Research in Asia (AARA) for postgraduate students to spend up to a year in the Asian region were extremely important—but under threat. I was also an enthusiast for “in-country” language study for undergraduate students which Murdoch University, where I had taught before the UWA, and some other universities had introduced as an integral part of their Asian Studies degree. The University Mobility in Asia and the Pacific (UMAP) student exchange scheme had been welcomed when it was introduced in 1991 but was presenting some problems of reciprocity. A workshop I organised for university and government representatives following the 1996 ASAA Conference did not completely solve them.

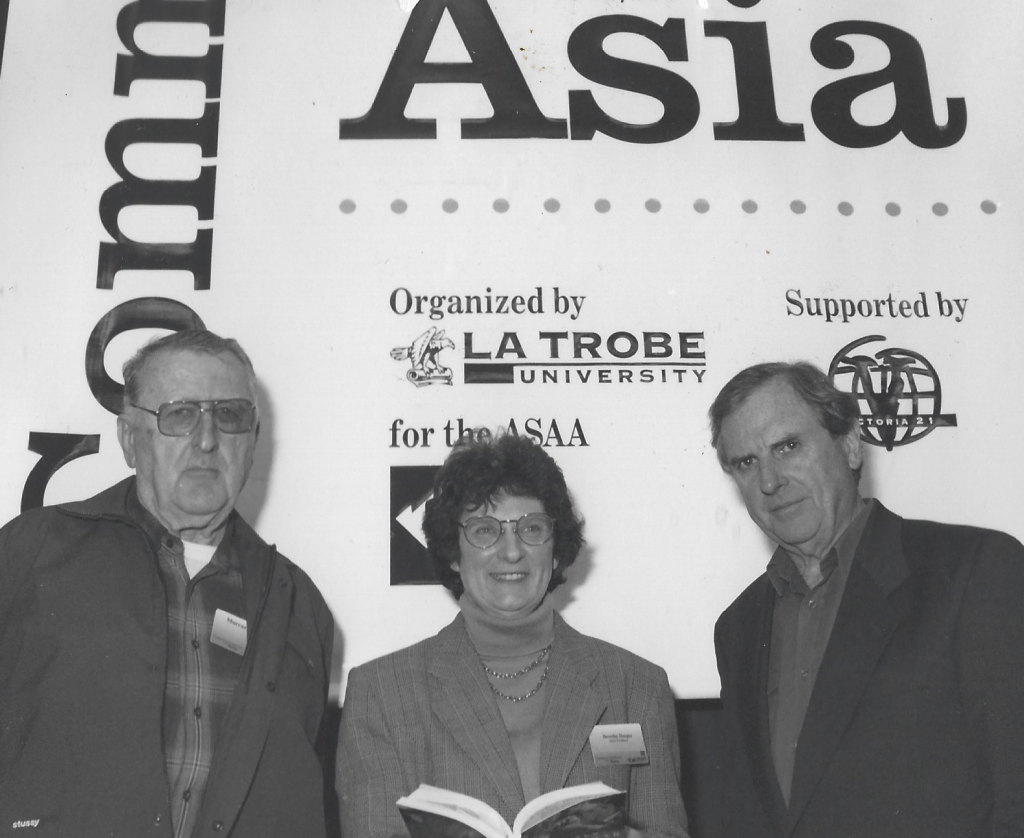

Image: Beverley Hooper with Australian foreign correspondent Murray Sayle and writer Christopher Koch at the 1996 ASAA Conference at La Trobe University (supplied).

What was it like for women academics in Asian Studies and in the ASAA during your time?

Women tended to be clustered in the more junior academic positions, particularly as language tutors, with very few in senior academic roles. The dominance of male academics also continued to be noticeable at the ASAA conferences I attended as a Council member and then as President, and the “big names” were still largely male. There were some women on the ASAA Council, though when I became President I was conscious that I was only the second woman to hold the position since the ASAA’s founding almost twenty years earlier. The existence of the ASAA Women’s Caucus (later the Women’s Forum) from 1978 had provided important opportunities for female networking and confidence-building, particularly among those researching the growing field of women’s studies. By the mid-1990s I was keen for this research to become somewhat more integrated into the academic “mainstream”, including the general ASAA conferences, while not lessening the importance of the Women’s Caucus and its activities. Participation in the wider sphere was important, I felt, not just for the scholarly field of Asian Studies but to make women researchers better known among senior male academics who still dominated university appointment and other committees.

How have things changed?

It’s a different world, just as it is for women in most professions. “The first woman to …” syndrome might not be completely dead, but the appointment of a female professor—or even faculty dean or vice-chancellor—is no longer worthy of particular comment. An important byproduct of the growing number of women academics in Asian Studies, particularly at a senior level, has been the increasing presence of female role models at all stages of one’s higher education and career.

In my entire Bachelor of Arts degree, only one of my lecturers was a woman. When I won the 3rd year Asian History prize, my (male) lecturer said to me: “You’ve done very well. Now you should get hitched to a rising star”! When I was doing my PhD at the ANU in the late 1970s/early 1980s, all the permanent academic appointees in the Department of Far Eastern History (later the Department of East Asian History), as well as all but one of the fixed term research fellows, were male. Admittedly that overwhelmingly male environment had started to decline somewhat by the time I was ASAA President, and is now largely a thing of the past.

Female representation on the ASAA and its activities has also increased. While I was one of only two women out of the Association’s first ten presidents, four (including the latest two) of the ten most recent presidents have been women. Viewing the very significant changes over past decades, though, can sometimes lead one to overlook the gender inequalities which continue to exist in some academic and other professional areas, especially at higher levels.

Why would you encourage other women to join the ASAA and become involved in the Council?

I think it’s important for women teaching and researching on Asia to join the ASAA because it is “their” professional association. First, the ASAA (as an area studies association) provides a forum both for making inter-disciplinary connections, particularly if one’s research is grounded in a particular discipline, and also for learning more about the latest scholarly research on other Asian countries. Second, at a time when some university Asian language programmes are being cancelled and even the Asian Studies programme I was appointed to develop over thirty years ago has been under threat, there is a continuing need for Asian Studies academics in all disciplines to band together as a group to protect, and lobby for, teaching and research on Asia. And that group, of course, includes women.

At the level of professional development, being on the ASAA Council gives one up-to-date knowledge of the current situation in the general Asian Studies field, as well as experience of discussing issues specific to Asian Studies. It is all too easy to become bogged down in the problems being experienced in one’s own university and even department and not to see the “big picture”.

Feature image: Beverley Hooper speaking at the 1996 ASAA Conference at La Trobe University (supplied).