Riyadh’s perceptions of ’enemy’ Iran are creating political tensions in the region

Beneath the strategic rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the latter’s perception of its Persian neighbour as an existential threat is an example of ‘ideological fundamentalism’ in operation.

International relations theorists Ken Booth and Nicholas J. Wheeler explain that when a state develops a perception of a counterpart based on what it thinks the other is, meaning its political identity or character, rather than how it actually acts, the state creates an ‘enemy image’ of that counterpart. In extraordinary cases, the enemy image also extends to the other state’s society, thus intensifying the other’s presumed malign behaviour.

The operationalisation of such enemy images, as exemplified by the way the Al Sauds view their Iranian counterparts, harms Saudi Arabia’s ability to find within itself the political will, clarity of thought and foresight to build a cooperative relationship with Iran for mutual gain. Moreover, the promotion of Saudi ideological antipathy towards Iran since its Islamic revolution in 1979 prevents rapprochement and exacerbates political tensions where Riyadh’s strategic interests compete with Tehran’s in countries such as Afghanistan, Bahrain, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, and Yemen, among others.

Ideological imperatives do not necessarily override political objectives and strategic interests. However, viewing the other as an adversary magnifies enmities, which acts to the detriment of diplomatic efforts to realise lasting political resolutions to conflicts.

Malign orientation

Three aspects of Saudi Arabia’s political and sectarian behaviour towards Iran underscore how its malign orientation has consistently gained traction: first, seeking Iran’s political disintegration; second, expanding its Salafist ideology; and third, persecuting adherents of Shi’ism within and outside its borders.

The implications of Riyadh’s revisionist orientation means that its strategic agenda threatens to push the Middle East towards greater instability. For instance, some of the ways in which the Saudi royal family’s destabilising policies have manifested in the past year include its opposition to the nuclear deal with Iran; its execution of Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, a prominent Saudi Shi’a cleric; and Riyadh’s announcement of a 34-state ‘Islamic military alliance’ to counter terrorism—albeit this group looks more geared towards pursuing a sectarian agenda, as it omits Iran and Iraq, both Shi’ite majority nations, as well as Syria. Other predominantly Muslim countries that have chosen not to be part of the coalition include Afghanistan and Oman, and Indonesia, which opted out of the coalition.

The challenge that ideological fundamentalism poses in Riyadh’s regional standoff with Tehran relates to how it has intensified the Saudis’ risk-taking behaviour. For instance, Germany’s intelligence agency, BND warned, ‘The previous cautious diplomatic stance of older leaders within the royal family is being replaced by a new impulsive policy of intervention.’

Saudi Arabia, not Iran, risks plunging the region into greater turmoil because it is willing to bear more costs to contain Shi’ism and diminish Iran’s regional influence

The BND’s report singled out the Saudi defence minister, 30-year old Deputy Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman, for his assertiveness, exemplified by his disastrous decision to intervene in Yemen and finance a full-scale proxy war in Syria.

The report claimed that, under his leadership, Saudi Arabia was ‘prepared to take unprecedented military, financial and political risks to avoid falling behind in regional politics’. What this means is that Saudi Arabia, not Iran, risks plunging the region into greater turmoil because it is willing to bear more costs to contain Shi’ism and diminish Iran’s regional influence. But, being increasingly assertive does not always pay off, a lesson that ideologically driven actors often fail to see, much less learn from in their dealings.

For Saudi Arabia, the mix of political and ideological imperatives for confronting the Islamic Republic of Iran emerged shortly after its establishment. Iran’s Islamic Revolution called into question Riyadh’s predominance and undermined the legitimacy of the Saudi ruling family by establishing a basis for an ideological challenge to the Kingdom’s self-declared leadership of the global Islamic community and its championship of its Salafi-oriented brand of Islam.

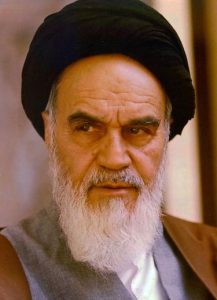

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s proclamation that monarchy was an illegitimate and un-Islamic form of government meant that he dismissed the Saudi version of Islam, and branded the latter as nothing more than American-sponsored due to the royal family’s dependence on Washington for its survival. Khomeini’s denunciations further heightened tensions as the assertion of undue influence from America was seen by Riyadh to threaten its custodianship of the two holiest sites in Islam.

Yet, despite Khomeini’s vocal opposition, Iran pursued a policy of pragmatic non-alignment under the slogan of ‘Neither East nor West but the Islamic Republic’, which on the one hand promoted its brand of Islam and on the other carefully avoided a military conflict with its regional rival, Saudi Arabia.

Although Tehran’s political calculation meant that it did not seek an armed confrontation, the same was not true for the Saudi leadership, as it chose to strategically challenge Iran in its war against Iraq and later to support the Taliban regime in Afghanistan.

Political challenge

Iraq’s invasion of Iran in 1980 enabled Riyadh and some of its Arab allies to challenge Iran politically and militarily to try to undo its revolution. Estimates show that Riyadh and Kuwait provided more than $50 billion in financial backing to Iraq, whose use of mustard gas against Iran is thought to have killed and injured around 100,000 Iranians. The American and Saudi assistance to Saddam Hussein and their disregard for the Iraqi military’s ‘almost daily use’ of chemical weapons against the Iranians expose how far the Kingdom was willing to go to cause Iran’s collapse.

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979, soon counterpointed by the Iran–Iraq War, provided an opportunity for the Saudis to weaken Iran simultaneously. The Taliban’s capture of political power in Afghanistan in 1996 was supported and welcomed by Saudi Arabia, whose endorsement of the late Mullah Omar’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan united them in opposing Iran.

Also, in the Taliban, the Saudis found a perfect host for their strain of Wahhabi-inspired Sunni Islam, a puritanical anti-Shi’a doctrine that culminated in the Mazar-e-Sharif massacre of thousands of Hazaras (a Shi’a ethnic minority) and the execution of nine Iranian diplomats. By supporting Iran’s adversaries Saudi Arabia substantiates its consistent support for anti-Shi’a behaviour and its revisionist orientation towards Tehran.

Shi’a threat

Like Saudi Arabia, some of the Arab Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states find the spectre of a ‘Shi’a full moon’ increasingly threatening. For instance, there is a strong perception among some of the GCC countries that Iran is behind all Shi’a activism. This was evident during the 2011 protests by Bahraini Shi’ites for equal rights against the Sunni-minority Al-Khalifa ruling family. The Al-Khalifas blamed Tehran for the protests and used the unrest to invoke sectarianism to bring into disrepute those seeking reform to end state-sponsored discrimination.

More recently, Bahrain revoked the citizenship of Isa Qassim, the most prominent Shi’a cleric in the Sunni-ruled Kingdom, accusing him of serving foreign interests and promoting sectarianism and violence.

Similarly, inside the Kingdom, Riyadh’s policy of violence, discrimination and disenfranchisement against its minority Shi’a population—an estimated 10–15 per cent mostly concentrated in the oil-rich Eastern Province—is emblematic of its ideologically rooted antipathy towards Iran and Shi’ism.

As a result, the Kingdom has shut out its Shi’a citizenry from key political, religious, social, security and educational sectors. The systematic marginalisation of Saudi Shi’ites by their government has generated a sentiment of inequality which came to a head in 2011 when protests broke out in the Eastern Province—inspired by the Arab Spring and events in Egypt—to demand the release of nine men held for years without trial.

As Riyadh rarely tolerates dissent, the Saudi National Guard responded with a heavy hand, and in clashes killed at least 20 young men and injured or jailed hundreds more. Riyadh was quick to blame Tehran for the civil unrest not only to delegitimise the protesters’ demand for reforms but also to paint them as agents of external states, thus limiting the possibility of cooperation between the two sects.

Revisionist doctrine

Given that Wahhabism focuses on the purification of Islam and seeks to return to its allegedly ‘true, original’ form, the doctrine is inherently revisionist towards adherents of Shi’ism and hence Iran. Even though Iran largely abandoned the exportation of its revolution to other countries in the 1990s, has downplayed sectarianism in favour of pragmatic political engagement and follows a policy of state-by-state interactions, Riyadh has not abandoned its anti-Shi’a behaviour or changed its malign orientation towards Tehran.

In addition, the Saudi ruling family’s dependence on the religious clergy for its own legitimacy necessitates that it sustain the Wahhabi doctrine that has positioned Saudi Arabia to become ‘the centre of doctrinal anti-Shiism’ within the Islamic world, as Toby Matthiesen writes.

The combined impact of the Saudi ruling family’s policy choices and its domestic political constraints creates significant pressure for it to continue to sharpen sectarian identities and classify Iran as an enemy. Barring a tectonic shift in the Kingdom’s enemy image of Iran, it is unrealistic to expect the Al Sauds to jettison their risk-laden behaviour.

The tragedy of the proliferation of an enemy image of Iran in the Saudi ruling family’s mindset is that it provides them with the justification to pursue a revisionist agenda against Iran and reinforces their perception of Tehran as an existential threat.

While such a strategic challenge to Saudi Arabia does not exist, the assigning of an enemy image to Tehran has exacerbated tensions between them and has done more harm to Riyadh’s regional standing than any gain it has made from its recent gambles.

Featured image

United States Defence Secretary Ash Carter welcomes Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud to the Pentagon, 13 May 2015. Ayatollah Khomeini dismissed the Saudi version of Islam, and branded the latter as nothing more than American-sponsored due to the royal family’s dependence on Washington for its survival. Photo: US Department of Defense. Wikimedia Commons