Evidence from a decade of data from the Australian Research Council

Australian governments tend to agree that Asia is vital to the national interest but are often unwilling to commit resources to fulfilling the potential of relations with the region. The ‘Australia in the Asian Century‘ white paper, which was commissioned by the Gillard government, is a good example of this tendency: the sentiments were good, but they were not accompanied by investments in new initiatives that might strengthen Australia’s ties to Asia. In so many respects, actions speak louder than words.

My goal here is to assess how Australian governments have realised this professed commitment to enhancing Australia’s relations with Asia, by examining public funding for research into Asian politics over the past 10 years. My analysis indicates that Asia remains a priority when funding politics-oriented research in Australia, but the type of research that governments prefer has changed markedly. In the past decade, I show, the priority shifted from politics at the local and communal levels, to national and international politics. I conclude by discussing some possible reasons for this shift, and its implications for the next decade of research into politics in Asia.

Funding for Asian politics within Australian Political Science

For most scholars who study Asian politics in Australia, the most valuable public-funding schemes are administered by the Australian Research Council (ARC), which ‘is the primary source of advice to the Government on investment in the national research effort’. ARC schemes are incredibly competitive, with ‘success rates’ usually at 15% or lower. When scholars with an interest in Asian politics apply for ARC funding, their broad ‘field of research’ is Political Science, and the sub-field of Government and Politics of Asia and the Pacific (which I refer to as ‘Asian politics’ or ‘politics in Asia’, for the sake of brevity). Across all ARC schemes, funding commenced for 163 projects in Political Science between 2010 and 2019, and 45 of these related to Asian politics.

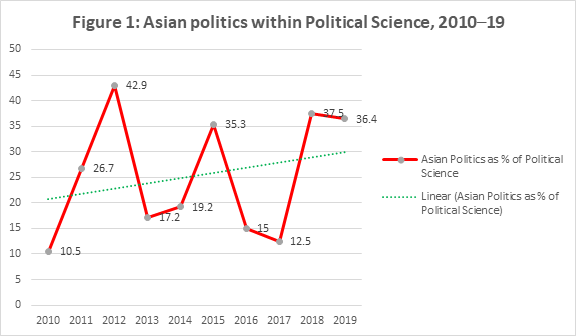

To a certain extent, funding for Asian politics is closely related to Political Science as a whole. The best annual performance for Political Science (29 grants in 2013) was early in the decade, and Asian politics had its best year (nine grants in 2012) at about this time. Similarly, the worst performance for Political Science in the decade (eight grants in 2017) was reflected in the similarly poor performance for Asian politics (one). However, the trend in funding was generally better for Asian politics than Political Science as a whole: the field overall had barely recovered from the 2017 slump by 2019, whereas Asian politics was back to the levels of the middle of the decade.

Figure 1 compares Asian politics projects to Political Science overall, and again shows that the sub-field fared comparatively well. Asian politics had a mixed record in terms of funding: 2012, 2015 and 2018 were its best years when compared to Political Science as a whole, and 2010, 2016 and 2017 were the worst. The dotted trend-line, however, tells us that Asia-based projects gained relative to Political Science overall. Projects that had some component of Asian politics increased steadily across the decade, and surpassed 35 per cent of all Political Science projects in 2015, 2018 and 2019.

Which type of Asia-related research?

As encouraging as this trend might be, it doesn’t tell us which types of politics-related research projects the ARC deems to be of ‘the highest quality’ and most likely to ‘ deliver cultural, economic, social and environmental benefits to all Australians’. We can get some idea about the ARC’s assessments by looking at changes in the coding practices of Asia-related political science research that were funded in the past decade.

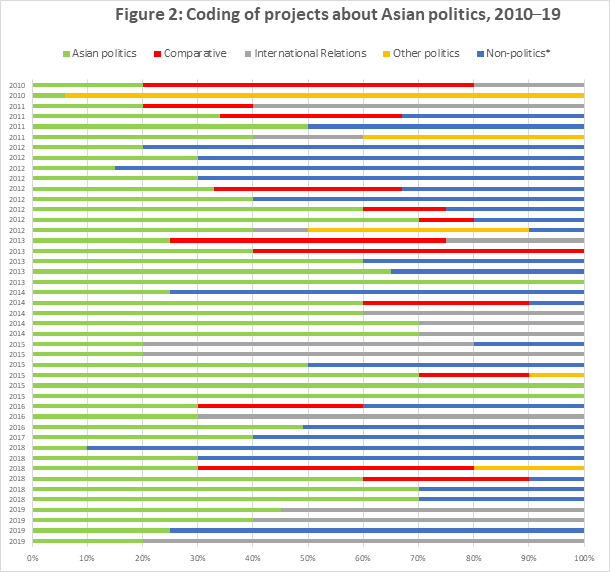

Researchers indicate their expertise when applying for grants by choosing particular fields of study, which in some cases equate to specific disciplines or sub-disciplines, each with its own code number. Applicants need to specify which proportion of their project should be allocated to a specific code. Some people might allocate 100 percent of their project to a single code, while others may split the allocation across multiple sub-fields. Since Asian Studies is an area of study rather than a discipline in its own right, projects relating to Asian politics usually involved a high degree of inter-disciplinarity. That is, they were rarely coded solely in terms of Asian politics and instead drew on expertise in a range of different fields both within Political Science and without (see Figure 2).

Source: ARC; * including sociology, public policy, history, and law

Figure 2 shows how the 45 projects in Asian politics were coded. For the most part, these projects were coded with other Political Science sub-fields, especially International Relations (‘IR’) and to a lesser degree Comparative Government and Politics (‘comparative politics’). However, by presenting the projects in chronological order, Figure 2 also illustrates that projects funded early in the decade were more likely to draw on expertise in comparative politics, and in fields from outside Political Science (such as sociology, anthropology, public policy, history, and law). IR, however, became increasingly important to research about Asian politics, especially from 2014. With the exception of 2017 and 2018, research into Asian politics was mostly coded with IR instead of other fields, including comparative politics.

The rise of International Relations in the study of Asian politics

The growing preference for aligning with IR was also evident in the topics of Asia-related politics research. The projects that commenced in the 2010s can be classified into four main groups: Chinese politics and policymaking (18 projects), politics and foreign policy in Southeast Asia (especially Indonesia) (13 projects), Australian foreign policy in Asia and the Pacific (9 projects), and other topics in International Relations (5). Within each group, however, there was a discernible shift towards more IR-focused research.

For China-related studies, which were the biggest group, the focus shifted from political ideology and social policy, towards centre–periphery relations and foreign policy. For the ‘ideology’ projects, researchers tended to draw on expertise in Asian history and comparative politics. For the ‘social policy’ projects, researchers often had expertise in urban planning and sociology, with less emphasis on politics. For the ‘centre–periphery’ projects, researchers tended to have expertise in comparative politics and public policy. The projects that focused on foreign policy, meanwhile, featured both ‘politics’ expertise and also IR.

After China, Indonesia was the country that featured most prominently in Asian-related politics research. Across the decade, there was a gradual shift away from standalone studies of Indonesia and towards cross-national studies of Southeast Asia that included Indonesia. Among the standalone studies, the focus shifted from national and local politics—which had a strong ‘politics’ component and drew on expertise in comparative politics—towards the foreign-policy implications of political change, emphasising IR and law. The comparative studies, meanwhile, contained both conventional political studies, which drew on expertise in comparative politics, and those that focused on the interface between politics and policymaking, which drew on expertise in public policy.

A separate but related group of studies focus on Australian foreign policy, and especially aid-delivery, in Asia and the Pacific. The ‘politics’ content of these projects was comparatively low. Researchers on these projects often had expertise in International Relations, comparative politics and policy studies rather than Asian politics. Most of these studies were conducted early in the 2010s, with none starting after 2016.

The general shift towards alignment with IRwas also evident in the remaining five projects that had some Asian politics content. Expertise in Asian studies was used to analyse the foreign policy of Asian states, especially towards the end of the decade.

One path or many for the study of Asian politics?

My analysis suggests that Asian politics, broadly defined, has fared comparatively well in the field of Political Science, but also that certain types of research projects, and researchers, have enjoyed more success than others. Projects related to foreign policy, for instance, have enjoyed success in ARC schemes, rather than those in social policy. There are several ways to interpret these findings, and I finish by offering some thoughts about the future of research funding for Asian politics.

A ‘structural’ interpretation would emphasise the partisan preferences of Australian governments and assume that funding decisions reflect these preferences. We know that some ARC applications have been assessed favourably by experts and recommended for funding by the ARC, but rejected by ministers. Labor governments may have favoured studies of local and national politics in the early part of the decade, and Coalition ones might have preferred the foreign policy-related studies in more recent times. Focusing on the ‘successful’ applications, however, tells us nothing about projects that were not funded. Without a fuller picture, this type of interpretation can only go so far.

An ‘agential’ interpretation, meanwhile, would be that ‘success’ in competitive grants schemes has more to do with applicants than governments. The changing makeup of projects relating to Asian politics might reflect the growth in enrolments in IR courses in Australian universities, and the gradual decline of Asian Studies. It could also be a response by researchers to the perceived degree of urgency about some topics rather than others.

A third interpretation is that some researchers in Asian politics have anticipated the preferences of government and tailored their applications accordingly, and have achieved success in highly competitive schemes that are administered by a funding agency which promotes world-class research, and does so by placing a premium on rigorous peer review, and assessment of ‘the quality, engagement and impact of research’. In some cases, at least, researchers have framed their projects as less about politics in Asia, but the politics of Australia’s relations with Asia. Such an approach would also seem to be compatible with the recent emphasis on ‘national benefit’ in grants schemes. Scholars of Asian politics have thereby illustrated one viable path to success in ARC schemes, but this need not be the only one.