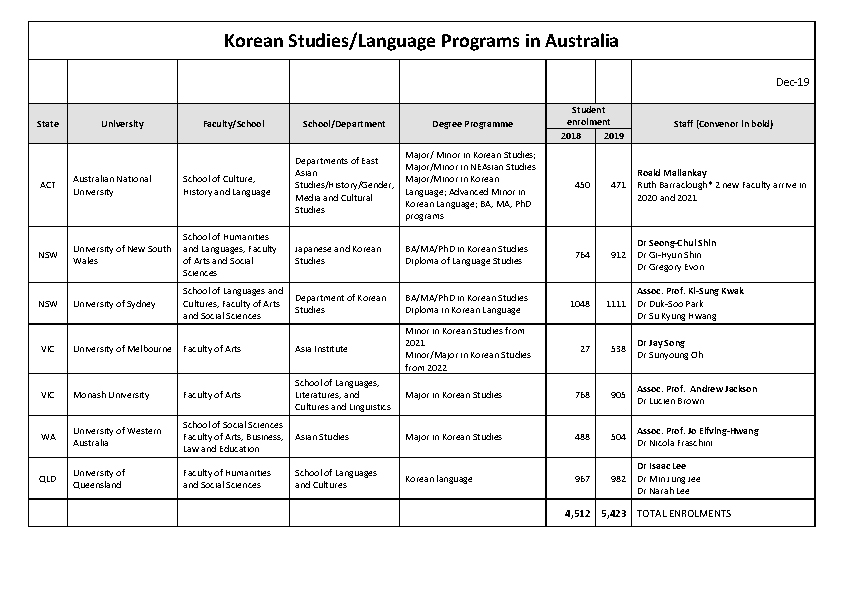

The story of Korean Studies in Australia over the last twenty years is a pleasing one, albeit with some highs and lows. In the 1990s Korean language programs were running in eight universities across Australia, including Swinburne, Griffith and Curtin Universities. Today there are fewer combined Korean language and Studies programs, but those that exist are larger and more established at the ANU (Australian National University), University of Sydney, University of Queensland (UQ), Monash University, University of Western Australia (UWA), and University of New South Wales (UNSW) with a new program just opened at University of Melbourne. In addition, key faculty in Korean Studies teach at UTS (University of Technology Sydney), Deakin University, University of South Australia (UniSA ) which has a King Sejong Institute, Macquarie University, La Trobe University, Wollongong University, and at other institutions.

Korean Studies has always had the advantage that there is something there for everyone: an ingenious language system; the pointy end of global politics and security studies; South Korea as a unique test case for rapid industrialisation; and of course studies of culture in literature, cinema, K-pop, dramas, food, fashion and translation.

Korean Studies in Australia has been aided in its development by a supportive and globally oriented South Korean government that chose to employ the model fruitfully utilised by Japan and France, to invest in the spread of its culture abroad. This was an outcome of South Korea’s global turn that can be dated back to two watershed moments: the successful hosting of the 1988 Seoul Olympics and the democratisation movement that pushed for a lifting of restrictions on overseas travel by Koreans, finally achieved in 1989. The Korea Foundation, established in 1991, was a welcome comprehensive manifestation of the ideal of “promoting understanding of Korea within the international community”. Along with PhD scholarships, the Foundation funds postdoctoral fellowships, lectureships and endowed professorial positions. In recent years the Academy of Korean Studies has emerged as an important funding partner of Korean Studies research and education in Australia.

This comprehensive approach that focused on scholarships as well as academic appointments has meant that the field grew just as universities began to ramp up recruiting new faculty. While twenty years ago it was sometimes hard to find qualified people to fill academic vacancies in Korean Studies, that is no longer the case. The Korean Studies academic community in Australia is made up of graduates of strong Korean Studies programs from all over the world, including Seoul National University, Queensland University, School of Oriental and African Studies, Sogang University, Princeton, University of British Columbia, Sheffield University, ANU, Pusan National University, University of Illinois, Yonsei University, Chicago University and Harvard University.

Korean Studies in Australia really originated in the 1960s, when studying Asia was much more about studying classical civilizations than it is today. At the ANU, Korean pre-modern history was taught from the 1960s in a Department of Asian Civilisations in a Faculty of Oriental Studies. Korean language (or vernacular Korean) was only introduced in the 1970s and the first modern historian of Korea was only appointed at the ANU in 1994. So Korea in the early days was both cultivated and overshadowed by strong China and Japan programs that highlighted classical humanities or civilisation studies as the pinnacle of the field.

Today a glance around the disciplines represented in Korean Studies taught in Australia reveals an expansive curriculum including politics, political economy, international relations, linguistics, literature and translation, film studies, history (Joseon Dynasty to contemporary times), religion, business, communication studies, and more. In teaching and research, the field employs an expansive definition of Korea to include South and North Korea as well as diaspora Korean communities in Asia, Australia and globally.

The traditional area studies approach of language led programs continues to be the bedrock of Korean Studies programs in Australia. In fact, it is in language learning that our programs have seen the greatest expansion. Figures commonly reported across all universities are of enrolments in Korean language programs trebling or more over the last ten years. In Korean Studies we have followed the principle that building programs around languages is the best way to proceed. Language courses have also proven to be more recession-proof than contextual humanities or social sciences courses, partly because they are perceived to be teaching an applied skill and equipping graduates for a more global job market. In Korean Studies, we have found that area studies are an excellent base for applying for external research grants as well as fund-raising and endowments.

Our greatest strength is our students, and our growth has been led by an increase in the number of undergraduate students taking Korean Studies. Students are flocking to learn Korean and learn about Korea, and that is a global phenomenon. Our challenge is to properly resource language programs, and to advocate for languages at both ends, in the school system and in graduate research programs. We need to ask: why is adequately staffing and resourcing our language programs so difficult? Korean Studies is nestled in the richest and most prestigious universities in Australia, enrolments have boomed over the last ten years, but constantly having to make the argument to fund new continuing positions is dispiriting and exhausting. At ANU it took us nearly ten years to create a new faculty line in Korean language teaching.

We also need to make the case that training in languages for our HDR (Higher Degree by Research) students is core business. In a competitive academic job market, PhD graduates in Korean Studies increasingly need to be both excellent researchers and accomplished teachers across both their discipline and in language studies. Almost without exception everyone who teaches in a Korean Studies Department in Australia also teaches language. Although on the one hand this is a product of budget constraints, we have turned it to reinforcing a comprehensive area studies approach to Korea with language as the foundation.

We are seeing much more collaborative work between South Korean and Australian based researchers than ever before, which is a rich and fulfilling trend. At the same time opportunities for our research and the research of our students to be published and disseminated have never been brighter. Korean Studies boasts an excellent suite of journals across South Korea, the US and Europe, and dedicated series in the university presses of Washington, Columbia, and California. In addition, the Asian Studies Association of Australia has the flagship journal Asian Studies Review and multiple publication series with Routledge, including the Women in Asia series.

Korean Studies is represented by the Korean Studies Association of Australasia (KSAA) and as the name suggests our relationship with colleagues in New Zealand is very important to us. The KSAA hosts an international conference in a city in Australia or New Zealand every two years, and on alternate years we run a postgraduate workshop. The KSAA conference is an extremely collegial gathering and has become a calendar highlight for scholars in South Korea, East Asia, Europe and the US.

Recent special highlights in Korean Studies:

- Scholarship program at UTS for students originally from North Korea, which provides 30 weeks of intensive English language training, a life changing experience

- Monash University’s successful Academy of Korean Studies grant of $1 million over five years to build Korean Studies program at Monash and host outreach events in metropolitan Melbourne

- New faculty positions at Sydney, Monash, Melbourne, UQ, UWA and ANU

Korean Studies has well and truly moved out from under the shadow of China and Japan. Future directions for the field include more comparative and transnational work; in history that might take the form of Empire studies or Cold War studies, while for contemporary politics the two Korea’s relations with powerful neighbours will likely shape the Northeast Asia region. North Korea’s rapid economic transformation is already stimulating new work in political economy, migration studies and gender studies. Another electrifying field is translation, as exciting new Korean fiction stewarded by talented young translators sweep global literary awards.

Along with our success, our challenges are formidable:

- Establish and properly resource robust pathways of language learning from school to university that equips graduates for a global job market

- In Australia, despite important inroads by the New Colombo Plan, we have yet to open the field of Asian Studies to indigenous students in any meaningful way. For Korean Studies one pathway is to bring in Aboriginal, Torres Strait and Pacific Islander students to learn about Korea through a study abroad program designed specifically for them

- Prepare to adapt to a rapidly changing NEAsia and new opportunities for engagement, research, education and policy outreach