Haunted Houses and Ghostly Encounters has recently been published by National University of Singapore Press as part of the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) – Southeast Asia Publications Series.

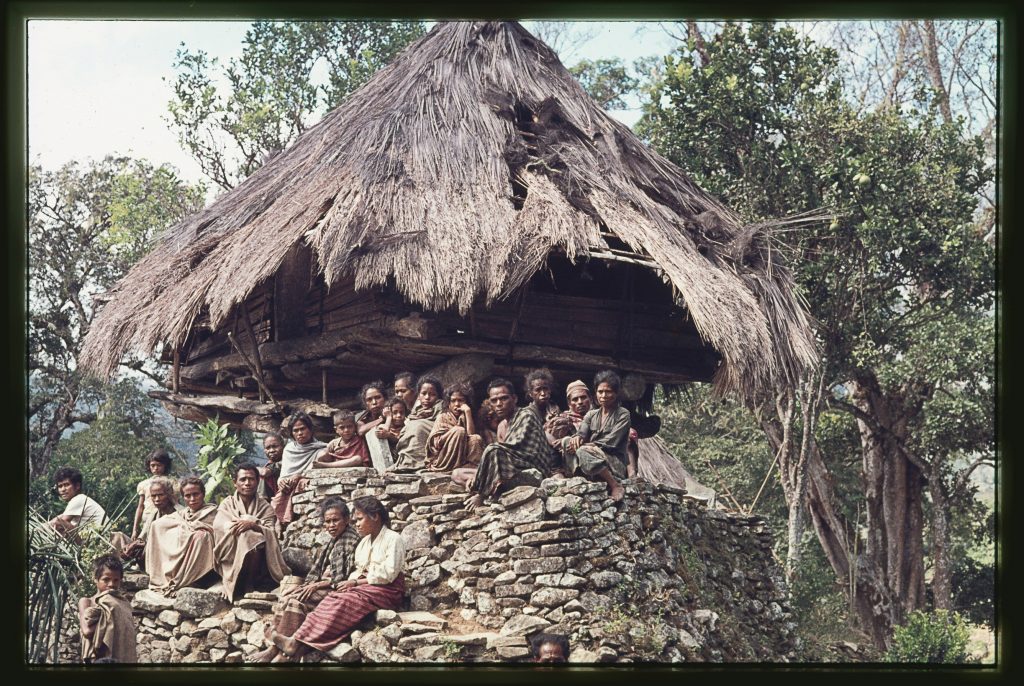

Haunted Houses and Ghostly Encounters presents the history of Western ethnography of indigenous religion––or animism––in East Timor during the final century of Portuguese rule, until 1975. The book addresses the relationship between spiritual beliefs, colonial administration, ethnographic interests and fieldwork. Each of the ten chapters is a narrative of the work and experience of a particular ethnographer. Across the six chapters of Part I, Colonial Ethnography, there come a govenor, a naturalist, a magistrate, a captain, an administrator and a missionary. Part Two, Professional Ethnography, plays out in the last few decades of colonial rule. It deals with American, British and Australian anthropologists, who (given their distinct ethnographic styles) I call the sentimentalist, the theologian, the apprentice and the detective. In a way, the book introduces the reader to ten versions of East Timor, differentiated not just by time but also by vocation.

Haunted Houses can be read as a storybook on Portuguese Timor. It includes stories about the magical powers and strange behaviours of colonial officers, scientists, priests and anthropologists. In the name of colonial governance, evangelical compulsions or fieldwork, they bury corpses or revive them, break native taboos and kill sacred animals (often for fun), set fire to villages or relocate them, seduce informants or get them pregnant, succumb to superstition or convert to paganism; they feed their children to spirits, play football with human skulls, participate in orgies, make love with snakes, get caught with their pants off, or take their own lives. It is about colonials who will do anything to domesticate wild, irrational animism, and it is about anthropologists who will do anything for data.

One must hastily add that the ‘local agency’ of natives is not overlooked. Colonial officials and anthropologists do unto natives in reaction to what natives do unto them. Among other things, the natives execute the oldest trick in the animist toolkit, which is to project their animist precepts onto outsiders. To foreshadow the plot (i.e. argument), the book opens with a story. A colonial administrator stumbles upon one seaside tribe who has just rescued their totem crocodile from an irrigation pipe. The administor realises that they see the crocodile as their ancestor. Nevertheless, shocked to see the natives pressing in against the feoriciously and hungrily writhing, lashing and snapping crocodile, the administrator orders them to kill it and bring it to him, since he wants a stuffed crocodile for his new museum. Alas, they refuse to kill their totem Grand Pa, so they deliver him alive, strapped to a stretcher. The administrator shoots the crocodile dead. This event, I propose, is neither incidental to animism nor symptomatic of its erosion at the hands of colonialism. Rather, it points to what I call ‘transformative animism’: human outsiders begin to stand in for spirits such that animistic ritual is ceremonially projected onto outside authorities. Seen as such, giving up their totem crocodile is not about deferring to colonial authority but about making an offering to a powerful administrator, a quasi-totemic figure in his own right.

This introductory anecdote is suggestive of a structurally similar relationship between spirits and outsiders, a relationship that asserts itself in story after story whereby Timorese treat spirits and outsiders in a comparable manner. In the end, the reader may be convinced that this convergence of the supernatural and human-colonial realms became consolidated with the turn-of-century pacification campaigns. As colonials assumed military control, they encroached upon the power fields of spirits, and what had long been animist ritual to address the proclivities of spirits became the expedient ‘transformative animism’ to address the proclivities of men and women from across the sea. Colonial ethnographers who served in Timor, and professional ethnographers who went there for field study, not only documented transformative animism, their bodies and souls also became wrapped up in it, inevitalby and often unwittingly.

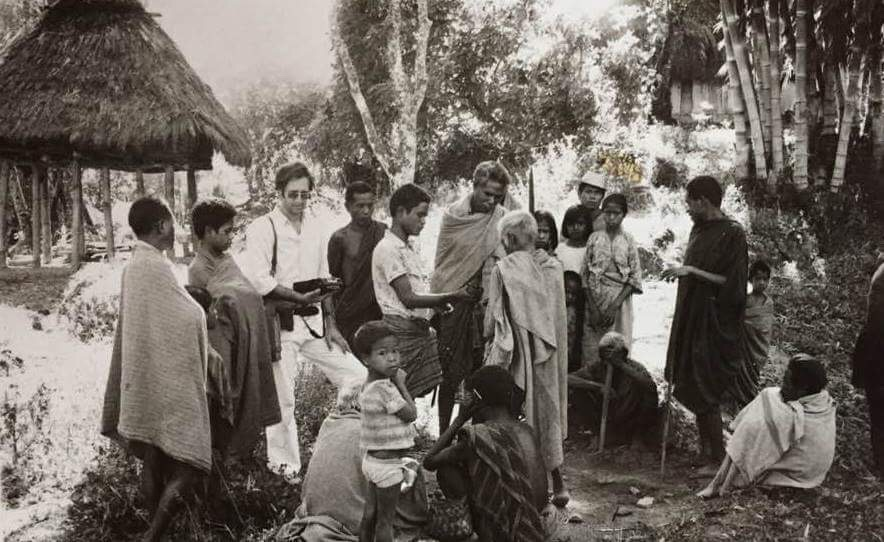

Haunted Houses takes published ethnography not only as source material but also as the object of study, since ethnography itself embodies transformative animism. The ethnographers treated in the final three chapters, moreover, were available to comment on ‘their’ chapters. They added empirical materials, qualified my interpretations, questioned them or became annoyed at them. I was naturally obliging, but sometimes obstinate. David Hicks was happy to be ghost, but not sure that his wife, Maxine, rated as a demonic seductress. Shepard Forman rejected the suggestion that he had artfully engineered the breaking of one taboo for the sake of hearing the otherwise un-utterable names of the dead. Elizabeth Traube insisted that field sex with informants was not something her conscience would permit, but agreed that the data gathering process was ‘erotically charged’.

Peering through representation to get at experience or history is not a one-way street. The 1975 invasion of East Timor also tempts us to look closely at representation and what was said and not said in academic works and forums during the quarter-century of Indonesian occuption. The aforementioned anthropologists as well as prominent Indonesianist, James Fox, became subject to my enquiries and conjectures about the academic silence on atrocities committed in East Timor. To what extent did scholars and institutions refrain from exposing the Indonesian government to keep fieldsites open or to defend other professional ambitions? Perhaps I broke some taboos myself in my candid treatment of anthropology’s vested interests which, I go on to say, remained concealed behind a veneer of cultural relativism and strategic essentialism.

Haunted Houses offers another way of telling East Timor’s final century of colonial history, since the selected ethnographies traverse critical phases or events in East Timor’s past, from the pre-pacification nineteenth century and the turn-of-century pacification campaigns through the decline of the native aristocracy and kingdoms, the relentless penetration of capitalism, the Japanese occupation and the postwar development era. Dispensing with historical detail, some readers less familiar with Timor may find refreshing the book’s framing of history within ethnography and story: dates and facts turn up amidst plenty of haunted houses, wicked witches and ethnographers in dire straits.

In the foreword, Douglas Kammen notes that a warning is in order. The book, he cautions, “is a history of ethnographic accounts based on an excellent selection of texts…, but it is not a history of Timorese animism per se”. Kammen’s comments raise fascinating questions of methodology not explicitly covered in the book. Haunted Houses, nevertheless, may leave readers wondering whether a single history of animism in East Timor that stands aside from the subjectivity of the ethnographic record, is even possible. If Haunted Houses offers an answer to this question, it is to be found not in the book’s claims but rather in its style; and what the book does not say is as important as what it does.