They’re idealists working out of the center of Javanese arts, culture and education. They want to promote harmony, but are bumping into difficulties with the acceptance philosophy of their guru.

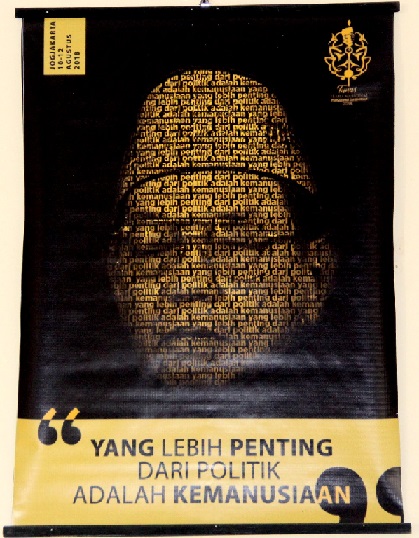

The fourth President of Indonesia, the late Abdurrahman Wahid, was better known as Gus Dur. So his followers have dubbed themselves Gusdurians.

Asian Currents teased out a few sometimes-taboo ideas with a group of sharp and bright young Gusdurians at their national headquarters in Yogyakarta.

When asked if they’d marry a person of another faith they found a score of excuses; most centered on the hurt it would cause their extended families and separation from friends and community.

They had lists of negatives; the joys of discovering difference and compromise seemed of little importance.

So better to marry a bad Muslim than a good Christian? “Well, not so easy.” said Ahmad Aminuddin, 26, who recognized the possibility that love can smite in unplanned ways. “There are other factors of customs and culture. We want to keep our identity. It’s complicated.”

Though not to someone brought up in the secular West where families often leave faith choices to their kids when they reach the age of discretion. But this is Indonesia where the question: ‘What’s your religion?’ is as common as ‘cold enough for you?’ in Hobart or ‘this one’s a scorcher, eh?’ in Sydney.

The organization has 110 branches around the archipelago and a few overseas, including Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand. It was established to keep Gus Dur’s nine values alive.

These are respecting and practicing faith, humanity, justice, equality, liberation, simplicity, brotherhood, chivalry and local wisdom.

The internationally famous humanist was 69 and in ill health when he died in late 2009.

His 19 months in office between 1999 and 2001 after the fall of the long time dictator and former army general Soeharto, followed by the brief Presidency of B J Habibie, were chaotic.

The near-blind Islamic intellectual and all-round funny man often diffused tensions by starting meetings with a joke, frequently poking fun at religion. He was a bad economist and administrator, but a good social reformer.

After being threatened with impeachment he yielded to deputy Megawati Soekarnoputri. To his biographer, Australian academic Dr Greg Barton, Gus Dur was a ‘non-politician politician’ who refused to make deals with the army, so gathered enough enemies to bring about his downfall.

He supplied ample ammunition by liberating the ethnic Chinese minority of racist controls, reforming the police, forgiving former Communists and preaching harmony.

The Gusdurians say they are a community network; their HQ is a small and sparsely furnished kampong house owned by Gus Dur’s eldest daughter, psychologist Alissa Qotrunnada. She was overseas when Asian Currents visited.

His activist second daughter Yenny runs The Wahid Institute research center in Jakarta.

Few Gusdurians ever encountered their hero, only his essays; they’ve translated 13 into English in the just-published Gus Dur on Religion, Democracy and Peace ‘to share his words with the world’.

Caricatures abound, showing the plump scholar looking more like Semar, the wayang character in Javanese mythology. At one level he’s a clown, but is also divine and wise. The name translates as ‘mysterious’.

The Gusdurians in Yogyakarta are all Muslims but in other centers like Malang, Catholics and Protestants are in the front ranks. Last December an unnamed group in the East Java city lined roads with posters urging Muslims not to wish Christians a Happy Christmas; the Gusdurians organized a rapid removal.

Gusdurians push multiculturalism but their concept would be better labeled ‘multiethnic within the Republic’; it’s not the definition used by nations with massive migration programs like Australia where people from across the world have settled.

For Aminuddin the term means Acehnese through to Papuans living together within the archipelago.

The more cosmopolitan Akhmad Agus Fajari, aka Jay Akhmad, national coordinator of the Gusdurians, has traveled overseas where Islam is the minority faith, so understands the broader interpretation.

At a 2018 convention which drew 650, he said the Gusdurians were not a fan club or supporter of the former president, just the new generation wanting to spread his ideas.

There’s another partially similar NGO operating in the Republic. Islam Nusantara seems to be better funded, producing well-made films promoting indigenous culture-based Islam as opposed to the puritan Saudi Wahhabism version that’s long been dominant. Akhmad said Gusdurians were “in line” with Islam Nusantara.

“Gus Dur is the tree – we’re the twigs,” he explained. “We need to see language and definitions in context. This is one of the challenges.” It’s a word that jumps into many of his statements along with “struggle”.

Another notion that sparks much heat and little light: What’s a liberal?

For fundamentalists it’s a synonym for Western decadence, for others it means freedom to think independently and be open-minded, difficult when some faiths demand rigid acceptance of their scriptures. They were surprised to know that in Australia the major conservative political party is called Liberal.

Nofa Safitri, 24, plays with these ideas like the academic she’s probably destined to become. Raised in Bukittinggi in West Sumatra she chose Yogyakarta’s Jesuit Sanata Dharma University for her education, dismissing relatives’ fears she’d be converted.

“I remember going into the classroom and seeing a cross on the wall,” she said. “I was at first concerned but five minutes later I’d accepted this was the environment. I never suffered discrimination.

“One lecturer joked about pictures of Jesus showing him with a ‘six-pack body’ and saying he needed to be fit to carry the cross. We couldn’t talk like that about our Prophet.”

Rifqiya Hidayatul, 25, has found that being a Gusdurian carries unexpected responsibilities. The night before she’d been contacted by a family seeking help for domestic difficulties; they assumed she’d inherited the former leader’s reconciliation skills.

Gus Dur’s thinking on the rights of minorities looks unassailably reasonable – till real events intrude. The Gusdurians were nonplussed by the idea of same sex weddings and gay clergy, unthinkable in the Republic but now accepted even in countries as deeply religious as Ireland.

Values shift. The wisdom of the elders doesn’t always answer dilemmas unforeseen last century. The Gusdurians have a model, but will have to till their own field.