The Australian Consortium for “In-Country” Indonesian Studies (ACICIS) — the organisation I head up — is here today as the direct result of previous Australian Government policy choices and public investment in Asian language education. Australia has done Asian language education well in the past. We could do it better again in the future if we chose, as a country, to do so. But we are in a hole. There has been no coordinated national plan involving Commonwealth and state governments, nor substantial or consistent government funding for the teaching of Asian languages (including Indonesian) in schools since the end of the National Asian Languages and Studies in Schools Program (NALSSP) in 2012.

This article is adapted from a presentation delivered on 7 April 2022 as part of the Monash Indonesian Seminar Series hosted by the Monash Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Centre. You can watch a recording of the presentation below.

The present is not entirely bleak. We do have the New Colombo Plan (NCP), an Australian Government program that has — since its establishment in 2014 — invested approximately $320 million into encouraging Australian undergraduate students to study abroad in the Indo-Pacific. This is a significant investment of public funding in Australia’s “Asia literacy” and, albeit indirectly, Asian language education. For comparison, Commonwealth expenditure on the NCP to date is about the same amount of money that the Australian Government spent on the entirety of the National Asian Languages and Studies in Australian Schools Strategy (NALSAS) over its lifespan between 1995 and 2002 — about $337 million in today’s dollars.

NALSAS, NALSSP and the NCP. Together these represent the three recent historical highpoints of Australian Government investment in Asian language literacy.

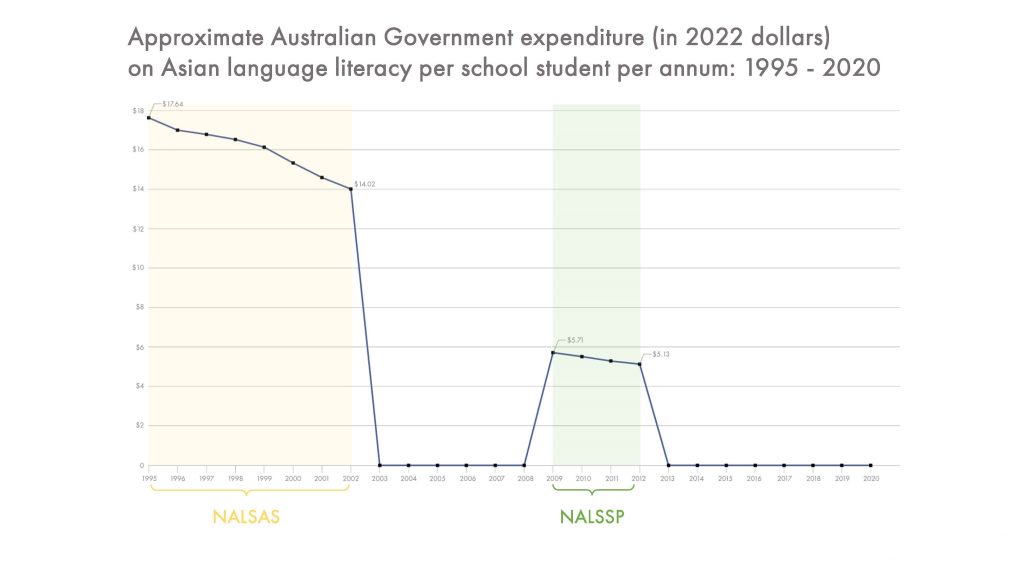

NALSAS was launched in 1995. It targeted a national Australian school population of 3.1 million students as of 1995. The scheme provided Australian Government funding to primary and secondary schools to establish language programs in four priority Asian languages: Japanese, Mandarin, Indonesian and Korean. Peak annual Commonwealth expenditure on NALSAS was $30 million per annum — or $49 million in today’s dollars: approximately $18 per Australian school student per annum on Asian language literacy.

In its first three years (between 1995 and 1997) NALSAS increased the number of government schools in Australia offering a priority Asian language by 44% — from 2,600 schools nationally in 1994 to 3,700 schools in 1997. The number of students at government schools studying a priority Asian language jumped by 60% from 324,000 students nationally in 1994 to 518,000 students in 1997. This was a remarkable achievement. Evidently, this breakneck growth was not sustained in NALSAS’ latter years. But these first three years testify to how quickly enrolment numbers can be turned around with adequate government funding.

Commonwealth funding for NALSAS was cut at the end of 2002. It was then partially resuscitated in 2009 in the form of the National Asian Languages and Studies in Schools Program or NALSSP.

Over four years, the Australian Government spent $62 million on NALSSP ($74 million in today’s dollars). Peak expenditure on NALSSP was less than half that of NALSAS — just $6 per Australian school student per annum and it was discontinued in 2012. There appears to have been no comprehensive review of its impact on the number of schools teaching, and students studying, the designated priority Asian languages.

If we graph Australian Government funding for Asian language education, we get this two-humped camel shape which traces the Commonwealth’s fitful and waning enthusiasm for funding the broad-based uptake of Asian languages among Australian school students.

The graph illustrates the peril of trying to prosecute a long-term national project that does not enjoy bipartisan support.

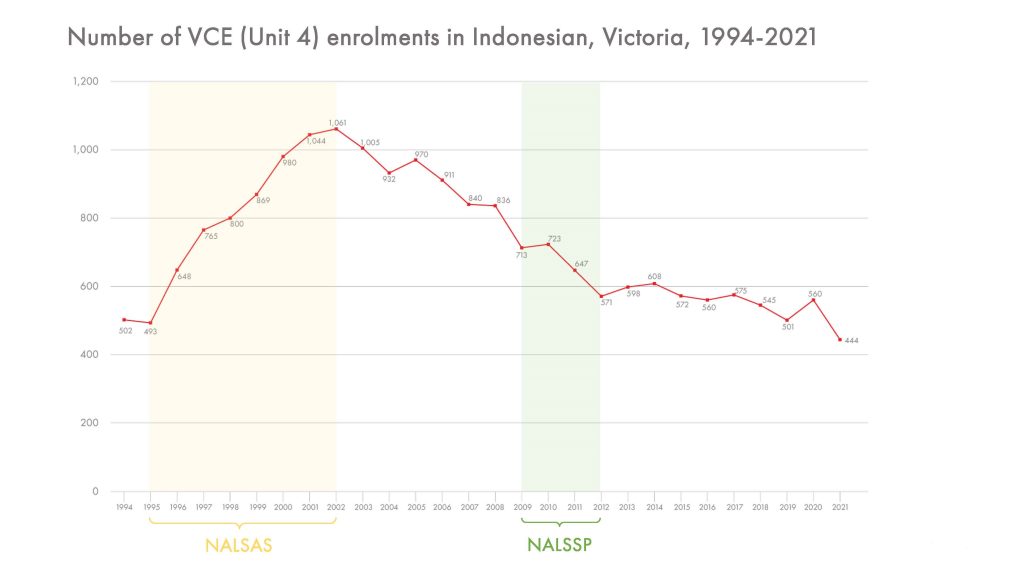

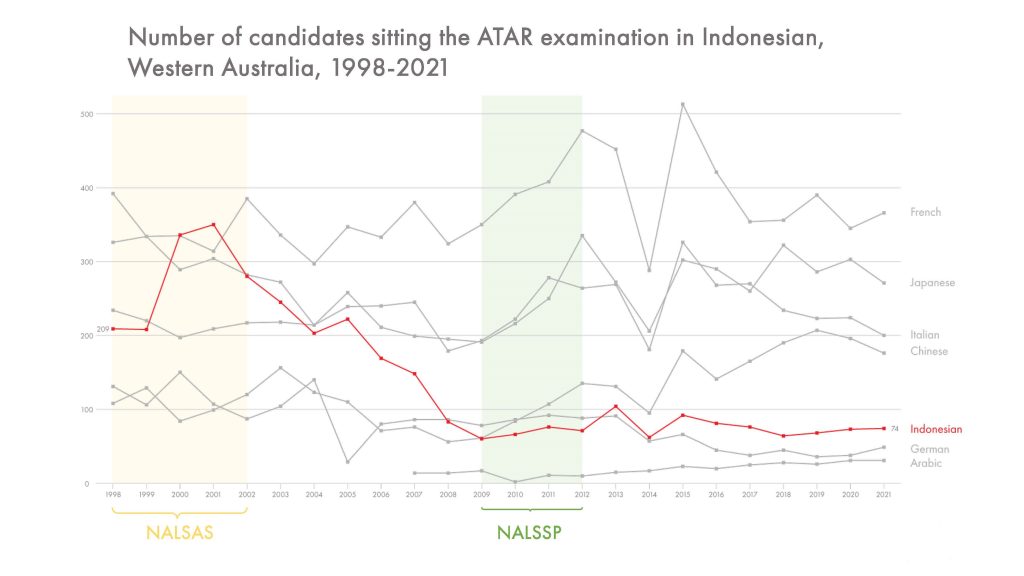

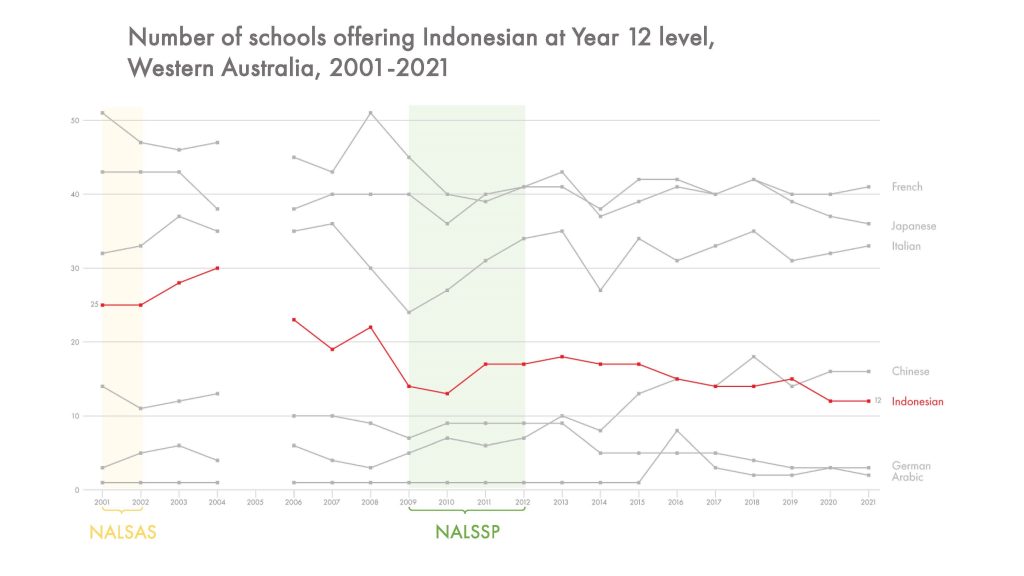

In measuring the impact of NALSAS and NALSSP it is illustrative to examine the teaching and learning of Indonesian at Year 12 level in two states: Victoria, and Western Australia.

Between 1995 and 2002, Victorian Certificate of Education (VCE) Indonesian enrolments grew rapidly and continuously — more than doubling from 493 enrolments in 1995 to a peak of 1,061 enrolments in 2002. During the six-year hiatus in Commonwealth funding between the end of NALSAS and the launch of NALSSP, annual VCE Indonesian enrolments dropped by 33% — to just 713 students in 2009. Enrolments rallied slightly in 2010 — the second year of NALSSP — but overall it appears that NALSSP had a negligible impact on Year 12 Indonesian enrolments in Victoria.

Year 12 enrolment data for Western Australia for the first three years of NALSAS is, unfortunately, not available. But, starting in 1999, we see a huge (68%) increase in annual Year 12 Indonesian enrolments during the latter years of NALSAS — from 208 students in 1999 to a peak of 350 students in 2001.

West Australian Year 12 Indonesian enrolments were already declining steeply during the final year of NALSAS before cratering catastrophically to just 60 students in 2009 during the hiatus between NALSAS and NALSSP. Enrolments rallied modestly in the second and third years of NALSSP before declining again in its final year.

In Victoria, there were 37 Victorian schools teaching Indonesian at Year 12 level in 1995.

By the end of NALSAS this had grown to 103 schools, and numbers actually peaked three years after the end of NALSAS in 2005 with 116 Victorian high schools teaching Indonesian at Year 12 (VCE) level. NALSSP appears to have had a negligible impact on the number of schools teaching Year 12 Indonesian in Victoria, but levels have never regressed to pre-NALSAS numbers, suggesting the original scheme delivered lasting infrastructure and communities of educators within Victoria. As of 2021, 62 Victorian schools offered Indonesian at Year 12 VCE level.

In Western Australia, the number of schools teaching Indonesian at Year 12 level peaked two years after the end of NALSAS in 2004 at 30 schools.

Between 2005 and the second year of NALSSP in 2010 this number fell to just 13 schools. Numbers rallied a little during the final two years of NALSSP and peaked at 18 schools in 2013 — one year after NALSSP ended. As of 2021, 12 WA schools offered Indonesian at Year 12 ATAR level.

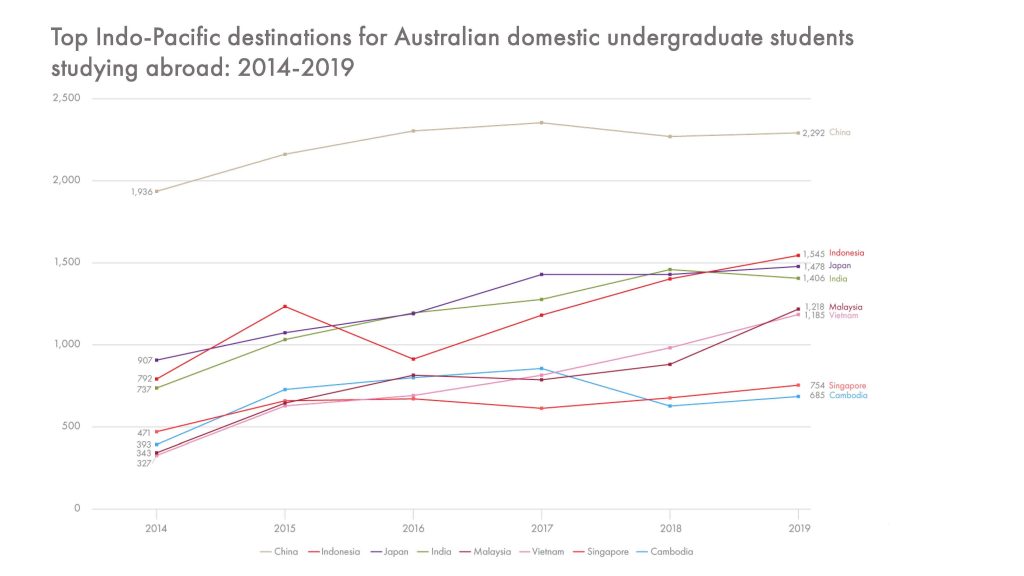

The New Colombo Plan was launched in 2014, targeting a national Australian domestic undergraduate population of approximately 750,000 students (as of 2014). The NCP provides Australian Government funding to support study and internships in forty Indo-Pacific destination countries. Interestingly, 70% of NCP Mobility Program funding from 2019-2022 focused on just nine key destinations: Indonesia, India, Japan, China, Vietnam, Singapore, Fiji and Malaysia.

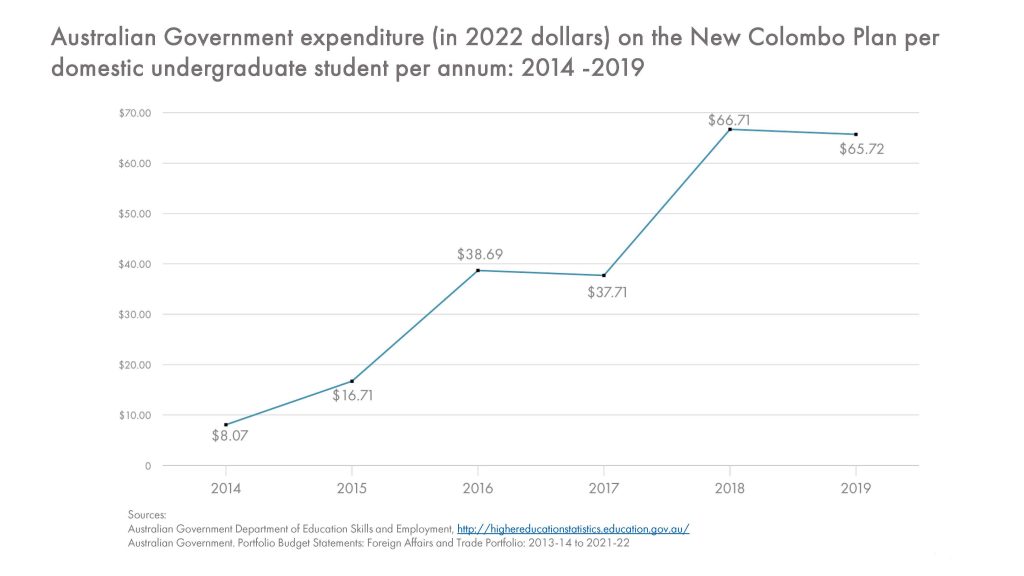

So far the Australian Government has spent $322 million on the NCP. This peaked at $54 million (in 2022 dollars) during the 2017-18 fiscal year, approximately $67 per Australian domestic undergraduate student.

The NCP is a much more costly program on a per student basis than was either NALSAS ($18 per student) or NALSSP ($6 per student) as it targets a much smaller student population — 750,000 undergraduates vs. 4 million school students.

In its first six years to 2019, the NCP has increased the number of Australian domestic undergraduates studying in the Indo-Pacific, from 8,437 students in 2014 to 15,440 students in 2019.

It has nearly doubled the number of Australian undergraduates studying in Indonesia and India annually, and nearly tripled the numbers studying in Vietnam and Malaysia.

NALSAS, NALSSP and the NCP represent the high-water marks — our greatest hits — in public funding for building Australia’s Asia literacy. Each demonstrates, to differing extents, that rapid, national, system-wide progress can be made — and I argue, only made — with adequate government funding. Government funding is not in and of itself sufficient to turn around the current downward trend in Asian language learning in Australia, but history tells us it is a necessary condition.

As I have argued previously, any Australian government intending to increase the number of students studying Asian languages at Australian schools and universities would, at minimum, need to restore public funding to something like the level that prevailed under NALSAS between 1995 and 2002 — approximately $71 million per year in today’s dollars.

We need a national working group to begin drafting successor legislation to NALSAS. We need to rally around the argument for reinstating Asian language literacy funding of $18 per Australian school student per annum — the level that prevailed previously under NALSAS. And we need to secure a total funding commitment of $71 million per annum from a combination of Commonwealth and state and territory governments.

We have historical precedent. We have the corporate memory. The next time a politician from either side wishes to sink personal political capital into this long-term national project, we need to be ready with well thought-out, properly costed, draft legislation broadly supported by relevant sectors and constituencies.

We do not want to miss the next chance to fund Asian language literacy in Australian schools properly — whenever, and from wherever, this opportunity arises. History suggests it could be a decade or two between drinks.

This article is adapted from a presentation delivered on 7 April 2022 as part of the Monash Indonesian Seminar Series hosted by the Monash Herb Feith Indonesian Engagement Centre. A full set of presentation slides containing more comprehensive versions of the data sets upon which this article is based are available for download here.