Students appear to be responding well to a novel approach to learning Hindi

Over the last two years I’ve started using comics increasingly to teach first-year Hindi. Responses from students have been positive. But it has also raised the question of why we might use comics to teach languages and what we can say about theoretical understandings of how comics work, and their use within language-teaching pedagogy.

Since Will Eisner’s pioneering Comics and Sequential Art (1985), there has been increasing interest in studying comics as a serious medium. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics (1994) introduced a new level of sophistication in understanding how words and images combine in comics to tell stories, and has been particularly influential in this development.

More recently, Neil Cohn has published a number of works, including Visual Language of Comics (2013), which examined the language of comic storytelling from a multicultural approach that draws on linguistics. There has also been a number of publications on the use of comics in English as a Second Language teaching, such as Stephen Cary’s Going Graphic (2004), Andrew Smith’s Teaching with Comics (2006) and David Recine’s Comics Aren’t Just for Fun Anymore (2013).

I’ve been teaching Hindi since the early 1980s and, since 2012, have been interested in the possibilities of using comics to create original teaching materials. In 2013, I reimagined the set of first-year materials I’d been teaching and changed the backstory, from a group of non-Indian friends arriving in India to one about a group of non-Indian and Indian friends meeting in restaurants, cafes and each others’ homes in a western country. The dialogues were written in collaboration with Hindi speakers and, as part of the process of recording, they helped decide what, to them, sounded like authentic Hindi speech.

In a sense, the answer to the question, why use comics, is obvious. It makes the dialogues accessible in the same way that most people find comics fun to read. As Scott McCloud has argued, comics have a range of advantages over text in telling stories. The very fact that the characters are cartoons means that readers can connect with them in a way that is not possible with realistic images. This seems to also set comic characters apart from videos or photographs. Comics give agency to readers, who have to imagine how the drawings relate to reality so they can imagine themselves into the story.

In visualising my teaching materials, I found continuity errors that I had not seen in the text form. I also began to see how I could create drawings that illustrated constructions like ‘this is’ and ‘that is’ to show how language relates to practice in a way that augments describing it in words.

Conventions

Comic readers also recognise conventions such as thought bubbles and gestures. This meant I could illustrate aspects of what characters were both thinking and saying. I also realised that by working out line breaks in speech bubbles, I could illustrate the use of ‘chunks’ of speech. Hindi grammar reflects who is speaking to whom, and in what context. In text, it is necessary to explain these constructions, but in comics it is easier to depict the contextual use of language in the combination of text and image.

My students engaged in a new way with the teaching materials. Out of the classroom, they read, listened and looked at them, and played with activities in which they had to make inputs to explore the materials further.

In the classroom, students print off materials from the Hindi Express website to work with the site. One of the first things I noticed when I introduced comics was that, given a comic with empty speech bubbles, the students would start to fill in the bubbles spontaneously. This creates a new class activity – copying dialogue and creating new dialogue to go with the comics.

The more complicated the interface, the more they treat the activities like levels in a computer game

This year, at the start of class, I began handing out comics with Hindi text. Students are much readier to do initial pair work at the start of class, speaking and translating the dialogues if they’re given them in this form than as text alone. There is also a tactile aspect to the combination of sound, text and image in online materials. Students click or touch on-screen elements in order to hear sounds or, for example, to change text or images.

Having watched students use the online materials since 2015, I’ve found most of them interact with the activities as if the main function is to solve how the interface works, rather than the language forms in them. Generally, the more complicated the interface, the more they treat the activities like levels in a computer game. Activities that have a simple interface and an element of random change work best, so that the focus is on language forms rather than learning the interface.

Measuring success

There are a range of questions as to whether you can measure success when using comics to teach a language like Hindi. Can comics attract new students? Can they encourage better retention of students? Can they deliver better learning results?

I don’t have the answers yet. Trying to do quantitative studies of students learning Hindi is a problem, because there aren’t enough Hindi learners in Australian universities to eliminate the variables from small sample sizes—often around twenty or so people in a class. It is possible, however, to provide new insights into how readers use online teaching materials by examining the logs for the Hindi Express site. Usage of the site increased significantly, from around 6,365 page views between May and December 2015 to around 9,672 page views from January to May this year. Insights gained from the logs will contribute to a final ePub version of the materials, which will be produced as a teaching resource for the university.

Although it’s too soon to quantify what impact comics are having in teaching Hindi, anecdotal evidence and comments from students strongly suggest that comics make the studying of Hindi dialogue more enjoyable—to the extent that students annotate and make notes on the cartoon printouts, and keep clicking on them, even in the middle of class.

The work involved in creating the comics, I’ve concluded, is worthwhile, as it provides exciting new pathways for students and teachers of Hindi to relate to and engage with learning the language.

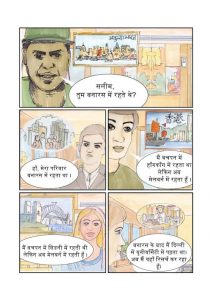

Featured image

Detail from comic lesson: ‘What is this?’