Following are some personal reflections and observations as to the state of anthropology of Asia in Australia, and its evolution over the past twenty years. I identify two trends that are in tension: a sector-wide neoliberal audit culture and a discipline-wide commitment to World Anthropologies. I suggest that Australian anthropology’s links to Asian Studies and Development Studies may help anthropologists to map a path forward through this environment. I offer these observations as a starting point for discussion.

Anthropology of Asia in Australia

My perspective on the discipline of anthropology in Australia is shaped by the institutions in which I was trained and employed; ANU (undergraduate), University of Melbourne (PhD), UNSW Sydney and recently returning to the ANU (employment). Two features stand out. First, while anthropology of, and with Aboriginal Australia has been central to the discipline, Asia and the Pacific have also been a focus, growing in importance since the 1960s (Robinson 2009). Language training is crucial for anthropologists, and no doubt the strength of anthropology of Asia is tied to the teaching of Asian languages at Australian universities (the decline of some language programs is therefore a potential risk). Further, the Australia Awards Scholarships encouraged many PhD students from Asia (in particular Indonesia) to train at Australian universities, further strengthening the anthropology of Asia in this country.

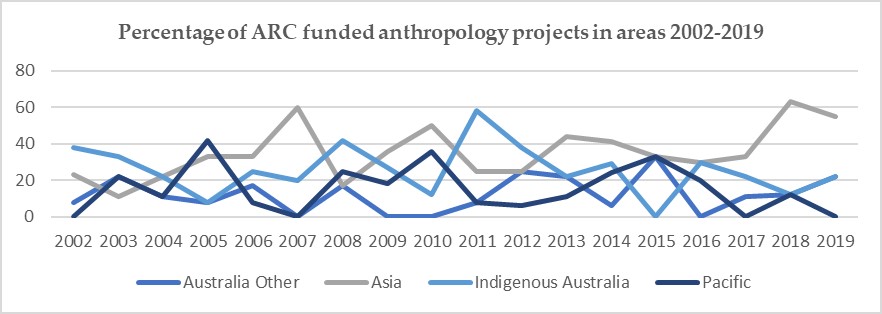

This strength is indicated by the success of anthropologists working in Asia in competitive research funding. The number of ARC funded projects on Asia with anthropology as their primary field of research has fluctuated in the period 2001-2019, yet has always held its ground against other research areas in the social sciences. Graph 1 shows the percentage of 1609 (FOR—anthropology) coded projects (FT, DECRA, DP, LP) on Asia compared to projects related to Indigenous Australia, Australia (other) and countries of the Pacific. Since 2013, projects on Asia have been the highest or equal highest percentage of funded grants.

A second feature of Australian anthropology is its relationship with Development Studies. The teaching of Development Studies by anthropologists is controversial in both fields. Development Studies scholars often point to a lack of specialist knowledge by anthropologists, while anthropologists often bristle at the ongoing association with the neo-colonial enterprise of development. Neither objection has made much sense to me. Anthropologists have been central to advancing development theory, which in Australian institutions has historically been taught from a very critical perspective (although this is changing). Anthropologists’ engagement with the ‘development enterprise’ has most often been to draw attention to the under-recognised negative consequences of ill-thought out interventions, as well as to support civil society groups and activists. As much of Australia’s aid is given to Asian countries, and Australia has a stake in their prosperity, stability and achievement of social justice, the anthropology of Asia arguably should play a central role in the teaching and practice of development.

On a practical note, the co-location of anthropology with Development Studies has brought much needed revenue to anthropology departments, particularly through lucrative Masters of Development programs. With the increasing competitiveness of ARC rounds, research for development funded through Category 2-4 grants is attractive. Further, the ARC’s recently introduced Engagement and Impact Assessment increases the incentives to have a practical impact from one’s work, which development research is well placed to do. For all these reasons there is often a mutually beneficial relationship between the anthropology of development and the anthropology of Asia. While this opinion is no doubt influenced by my own experience and training (Toussaint 2018 for example makes no such connection), the number of development studies programs primarily taught by, or co-located with anthropology (at a minimum six: Adelaide, ANU, Melbourne, Monash, Macquarie, Sydney), suggests it is at least a noteworthy feature of the discipline. I argue below that these features come with opportunities and responsibilities.

A challenging environment

A neo-liberal audit culture within the university sector has affected all academics in the Humanities and Social Sciences, but arguably anthropology has been particularly challenged. Ethnography, which remains central to the discipline’s identity, takes time: time in the field, and time to write with sufficient richness and depth. Monographs are highly prized, while citation counts for individual articles are lower compared to other disciplines. None of these features stand anthropologists in good stead in the current environment. Reduced government (ARC) funding for research in the humanities and social sciences has coincided with reduced university budgets, meaning less funds for field research, fewer sabbaticals, and increased teaching loads, all of which frustrate ethnographic research. Performance regimes, often modelled on STEM disciplines, punish academics in disciplines with low citation rates, fail to recognise books as significant achievements, and set unrealistic benchmarks. The consequence is that even leading anthropologists can be seen (or portrayed) as under-performing, creating enormous anxiety and insecurity for all.

My sense that anthropology departments have been in decline over the past 20 years, partially on account of these trends, is based on recent experience within a university that prioritises STEM disciplines, and hence partial. Less impressionistic is the poor performance of anthropology departments in ERA evaluations, where only 3 out of 11 institutions were evaluated as above world standard in 2018 (ANU, Macquarie University and University of Western Australia). In comparison, 8 out of 19 Human Geography departments are above world standing, and 15 out of 28 Sociology departments. If the example of UNSW is anything to go by, the mediocre performance of Australian anthropology departments is not on account of a lack of excellent anthropological research. Many anthropologists have found homes in other programs: Environmental Humanities, Public Health, Urban Planning, Technology Studies, and Asian Studies. The membership of the Australian Anthropological Society also remains robust, at over 600 members. Whether or not anthropologists should therefore be overly responsive to externally imposed indicators is something I return to briefly below.

World Anthropologies

There are different kinds of imperatives in the discipline at the international level. Anthropology has long recognised that the discipline is dominated by a ‘core’ consisting of scholars in North America and Western Europe (Chibnik 2016; Reuter 2015). The leading journals advancing the discipline are all based in North America and Western Europe, the scholars of which dominate authorship. Barriers such as language, money and the refereeing process disadvantage anthropologists in Asia (and elsewhere) who consequently have fewer opportunities to shape the discipline (Mathews 2015). Technology, higher incomes and English language training are levelling the playing field somewhat, but anthropology is yet to overcome the dominance of the Euro-American style of anthropology. Nations and regions have distinct ways of doing and communicating anthropological research (Mathews 2010). While difficult to generalise, anthropology within Asia tends to emphasize rich ethnographic description over theoretical discussion and is oriented towards national development or social issues (Goh 2015; Mathews 2010). In contrast, North American scholarship is theory driven, ethnographic research is put to the service of offering broader explanations relevant across contexts, and is presented in a literary style (Chibnik 2016). As the best journals are based in Euro-America, they publish articles that conform to that style, making it difficult for Asian-based anthropologists to break into them, while also disadvantaging Australian anthropologists.

An important trend at the international level in response to these issues is the emergence of ‘World’ or ‘Global’ Anthropologies (Reuters 2015). Globalizing and decolonising knowledge has become an urgent task over the past 20 years, with increasing acknowledgement that the lack of recognition and respect of the world’s ‘multiple anthropologies’ weakens the discipline, and that it will benefit from incorporating a diversity of voices and styles in an enlargement of the anthropological horizon (Restrepo and Escobar 2005). In 2004, the World Council of Anthropological Associations (WCAA) was established as a representative body in which the diversity of national Associations are given equal weight, extending the work of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (IUAES, est. 1948) to offer a more inclusive space for dialogue and scholarly solidarity. Other initiatives include the creation of a section ‘World Anthropology’ in the leading journal American Anthropologist, and the entry of new journals based in Asia, such as Asian Anthropology.

Australian-based anthropologists have been central to these efforts. Thomas Reuter (2015) has been both an intellectual leader and activist in this space, including being a cofounder of WCAA. Greg Acciaioli has been an active member of IUAES, while anthropologists such as Kathryn Robinson have spent a career mentoring anthropologists from Asia to increase the impact of their scholarship. Many more promote and elevate the work of colleagues in Asia through genuine collaborative partnerships, citing the work of Asian anthropologists, assisting them to develop the modalities of research and communication to enhance their international reputation, and publishing their own work in Asian languages and in regional journals. The infrastructure of Asian studies—language training and a critical mass of scholars conducting research on various aspects of a country or region—enhance Australian-based anthropologists’ ability to contribute to these disciplinary ambitions.

Anthropology with Asia

Australian anthropologists working in Asia are therefore well placed to make important contributions to ‘World Anthropology’: to be a training ground for Asian anthropologists, to enrich the scholarship out of Asia, and to build mutually beneficial partnerships with Asian anthropology departments. Indeed, we benefit enormously from doing so, in terms of the quality of our scholarship, and our ability to have a positive impact in the societies where we work. Further, as funding for humanities and social sciences are cut in Australia, the investment of Asian governments in the same offers new possibilities for international collaborations. The emphasis of much anthropology in Asia on practical-oriented research to address issues of national importance, often in collaboration with the government, may not suit all, but does provide a means to increase the social impact of our research. There is also a continued role in supporting Asian-based anthropologists engaged in activism and social or political struggle, at times in opposition to state and national objectives (Goh 2015). That such research can attract category 2-4 grants is not an insignificant consideration in these cash strapped times.

The question is to what extent is a commitment to democratising knowledge production in anthropology possible within the institutional conditions outlined above. Reuters (2015b) states that one must take a ‘hit’ when publishing in non-Western (and hence less prestigious) journals. I have been in university meetings where we are explicitly told to stop publishing ‘crap’, meaning anything that is not Q1, making co-publication with less accomplished scholars risky. Mentoring Asian-based colleagues in the writing and rhetorical styles acceptable to leading journals may be one task too many in a day filled with administrative tasks. While these may be valid reasons for ECRs to concentrate on their own careers, many of us have a responsibility to take the example of our senior colleagues who generously give their time and efforts to build anthropology with Asia for Australian anthropology.

References

Chibnik, Michael (2016) From the Editor: World Anthropologies and AA, American Anthropologist, 118(3): 479-482.

Goh, Beng-lan (2015) A Perspective on Anthropology from Southeast Asia, American Anthropologist, 117(2): 379-383.

Mathews, Gordon (2010) ‘On the Referee System as a Barrier to Global Anthropology’, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 11(1): 52-63.

Mathews, Gordon (2015) ‘East Asian Anthropology in the World’, American Anthropologist 117(2): 364-383.

Reuter, Thomas (2015) ‘Imagining globalization in anthropology: Diversity, equality and the politics of knowledge’, Focaal 71(2015): 18-28.

Robinson, Kathryn (2009) Anthropology of Indonesia in Australia: the politics of knowledge, Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs 43(1): 7-33.

Toussaint, Sandy (2018) ‘Australia, Anthropology in’, in H. Callan (ed.) The International Encyclopaedia of Anthropology John Wiley & Sons.