In the News

| In Sri Lanka the brutal civil war, which took nearly 100,000 lives and seemed so intractable, has suddenly ended. In May 2009 the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) crushed the decades-old separatist campaign waged by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and killed their elusive and ruthless leader Velupillai Prabhakaran. It is important to note that China underwrote the war against the LTTE. When the United States stopped direct aid to Sri Lanka because of its human rights record in 2007, Beijing came to Colombo’s rescue. China’s armaments (and their ally Pakistan’s) gave the GOSL the firepower to smash the Tiger’s highly trained war machine.

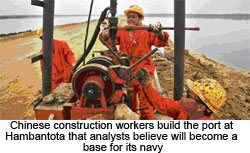

China is building a $1 billion port in Hambantota in the south. The Times of India reports this as part of China’s ‘string of pearls’ strategy to control crucial international passageways for trade and oil between the Indian and Pacific oceans. China is now the biggest foreign donor to Sri Lanka*1. The military victory was absolute. However, local and international human rights groups have called for inquiries into the deaths of thousands of Tamil civilians in the final months of the war when a ferocious GOSL bombing campaign was conducted away from the eyes of the world’s media*2. The GOSL claimed the casualties occurred because the LTTE leaders were making hostages of their own people, using a ‘human shield’ as the army advanced on their final stronghold. However, a furor erupted in August when Channel 4 in Britain aired video footage from Journalists for Democracy in Sri Lanka allegedly showing government troops summarily executing Tamils*3. Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapakse has been dubbed Hela Raja, the ‘king of the island’ for winning the ‘unwinnable war’. The Sinhalese, who make up 74 per cent of the population, are triumphant. The Tamils who are a minority (13 per cent) are vulnerable and apprehensive. The question now is: can this president win the peace? Can he reassure the Tamil people, who trace their ancestry back over 2000 years on this idyllic island, that, although they are a minority, they are equal and valued citizens of the new Sri Lanka? |

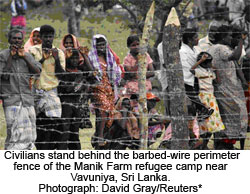

Since Sri Lanka’s independence in 1948 Tamils have claimed that political, economic and racial discrimination has been commonplace at the hands of the central governments controlled by the Sinhalese majority. This lack of inclusion in the nation-building project, they argue, drove the Tamils to support the armed struggle for a separate Tamil state. The most contentious issue is the fate of almost 250,000 internally displaced people (IDPs). These Tamil families are non-combatants who once lived under the tutelage of the LTTE in a de-facto state it had carved out of the north and the east of Sri Lanka, the area claimed as ‘Eelam,’ an ancient Tamil homeland. They have been the innocents caught in the crossfire, and they have been displaced many times before as the war raged around them. They are now incarcerated in government detention camps as the monsoon rains descend, bringing fears of disease and death. Claims of disappearances and maltreatment abound. The GOSL argues that they cannot return to their villages for two reasons. Firstly, time is required to ‘de-mine’ the areas that were recently the site of a ferocious war. And second, there may be LTTE cadres hiding amongst the civilians who must be weeded out as a matter of ‘national security’. The UN Human Rights Representative Walter Kaelin has insisted that the IDPs should be processed quickly and allowed to return to their homes or to host families in the community*4. The International Crisis Group told the European Parliament in early October that ’such restrictions on freedom in the absence of due process are a violation of both national and international law’*5. The incarceration of Tamil civilians by the GOSL is highly sensitive and symbolic. The huge Tamil diaspora scattered in Canada, Britain, Europe and Australia watches with trepidation. Boatloads of fearful Tamils from the north are now risking their lives to seek refuge elsewhere. The fate of the IDPs is viewed as a litmus test of how Tamils will fare under majority Sinhalese rule unhindered by a countervailing force. In essence, the diaspora supported the fight for Tamil rights, even if a majority may have abhorred the methods used by the LTTE to prosecute their case. Therefore a failure by the GOSL to free the IDPs and treat them as respected citizens today might only fuel support for a new (armed?) struggle tomorrow. Unfortunately, the lessons of history are not always learned. A corollary is that President Rajapakse may have trouble turning off his huge war machine. The army is now more powerful than ever and the fragile institutions of democracy that suffered while the all-out war was being prosecuted are still weak and ineffective. |

Civil Society is largely silent and fearful in the face of arrests and killings of those who have dared to question the way the victory was won. Dissenting opinion against state policy is portrayed as unpatriotic and subversive. Yet the popularity of the government is stronger than ever. A string of recent provincial election victories by the governing party has indicated a possibility of early national polls. Rajapakse may also call forward the presidential poll (due in 2011) to cash in on his own popularity as a strong man. Some commentators even suggest that the hubris of the president may lead to constitutional changes aimed at extending his hold on power beyond his impending second term. Unfortunately, international calls for an end to triumphalism may fall on deaf political ears. But whatever the president decides, he may find that making peace is harder than waging war. In a statement on Sri Lanka to the Australian Parliament on 14 September, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Stephen Smith, spoke of the urgent need to resettle the IDPs and to move towards political reconciliation. He said:

These are wise words from a friend of the Sri Lankan people. But if Australia is to remain a friend of the Sri Lankan people then it must accept that IDPS, and others like them from Afghanistan or Iraq, have a right to arrive here and make their claims under the international refugee convention which Australia and over 140 other countries have signed and ratified. It is important to note that Indonesia is not a signatory to this convention. |

|

Larry Marshall is the Project Officer for the Centre for Dialogue at La Trobe University. He was born in Sri Lanka. References:

|

||

REBUILDING SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITIES IN THE WAKE OF DISASTER |

|

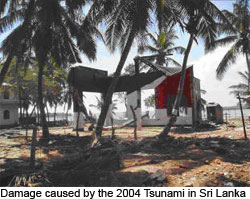

Communities in Indonesia, the Philippines, Taiwan, Samoa, India and Vietnam are reeling from the impacts of recent catastrophic earthquakes, floods, cyclones and tsunamis. A study by Melbourne researchers into rebuilding communities in Sri Lanka and India following the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami may point the way to faster recovery for disaster-ravaged communities. Improving the effectiveness of resettlement programs in current and future emergencies is a key development priority which demands attention from governments with an interest in promoting regional social and economic stability. In addition to their catastrophic short-term effects disasters sharply reduce employment and output and strain limited state capacity, increasing poverty and inhibiting the prospects for longer-term economic growth and social stability. Over 95 per cent of those made homeless by natural disasters are from developing countries, and the vast majority of the developing world’s population is located in Australia’s Asia-Pacific neighbourhood. During the final two decades of the 20th century the number of disaster-related homeless in developing countries increased by an average 6.5 per cent annually (Gilbert 2001), while in the last five years millions have been rendered homeless by catastrophic hydro-meteorological and geological events in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, China, Myanmar and India. Permanent resettlement is one of the highest priorities in post-disaster reconstruction. Stable and decent housing is essential in restoring morale and living standards, enabling the normalisation of family life, providing households with a threshold of security to support the resumption of economic activity, and communities with a platform for the rebuilding of markets, social networks and social and economic infrastructure. As the sustainability of resettlement programs depends on access to employment and the building of stable and inclusive social institutions, the cross-sectoral integration of housing with livelihood and community development planning is crucial. Programs that are poorly targeted do not take sufficient account of local labour markets, or of people’s needs and preferences with respect to location, housing type and neighbourhood design, and run a high risk of generating ongoing poverty and social conflict. The development of measures that support the effective rebuilding of social structures and economic activity is key to minimising adverse outcomes. There is a clear need for extensive multi-disciplinary research on how best communities can recover from disasters and rebuild sustainable and resilient settlements. This three-year research project—Rebuilding sustainable communities: assessing post-tsunami resettlement projects in Indonesia, Sri Lanka and India—funded by AusAID and an ARC Linkage grant, commenced from January 2007 and focuses on the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the most destructive disaster in recent global history. |

It examines selected housing resettlement programs in southern India and southern and eastern Sri Lanka, in diverse locations ranging from a major urban centre to a peri-urban development bordering a regional town and remote rural settlements. The aim is to draw lessons that can inform future policy and practice in housing design and delivery, livelihood planning and community development. The research team includes researchers with backgrounds in sociology, geography, development studies and architecture. The methodology, which involves a careful integration of methods used by them successfully in other projects, includes the following components:

The key findings of the research will be presented in a report to AusAID in March 2010. Some preliminary findings are briefly outlined below: Income, poverty and livelihoods: Poverty rates in the case-study locations were above the national average, and about two-thirds of households reported a post-tsunami decline in their incomes. In both India and Sri Lanka, the large majority of case-study households derived their income from the informal sector. Although the fisheries sector remains the most common source of household income overall, there has been significant movement out of fisheries and into construction, transport, non-farm microenterprises and work abroad. It is noteworthy that a change of occupation is associated with an increased likelihood of an improvement in incomes: around 60 per cent of primary income earners who took up a new occupation after the tsunami reported increases in their incomes, in comparison with only 27 per cent of those who retained their pre-tsunami livelihoods.

In most of the case study communities, particularly eastern Sri Lanka, where the long drawn-out ethnic conflict has greatly diminished income and livelihood options, |

remittances from migrant workers constitute an important source of income. Community rebuilding: Even after a number of years, there are fears of another tsunami, especially in communities living near the sea. Relocation has often been necessary and even welcomed by many who experienced the tsunami, but it presents big challenges for rebuilding an inclusive sense of community, especially in communities where there have been pre-existing social ‘vulnerabilities’ and ‘fault-lines’ resulting from poverty or entrenched social conflict. While there is an ever-present danger of aid dependency, especially in communities that have learnt to take advantage of any available opportunities, the bigger danger is when aid agencies do not understand the need to move from the relief phase to the community development phase of disaster rehabilitation. Field investigation indicated the difficulties of coordinating a range of actors—national and local governments, international and local NGOs—and inappropriate needs assessment and wastage of aid allocation after the tsunami due to hasty program delivery. A slower and more deliberate process might have resulted in more integrated planning of resettlement estates and indeed, where this was done, community satisfaction appears to be higher. Specific challenges arise in implementing and sustaining resettlement programs due to ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka and socially entrenched divisions in India—religion, caste, class, gender, etc. A range of longer-term needs that should be addressed in planning new settlements for disaster victims are being identified in this study. Housing and infrastructure: In both countries, although there are some notable exceptions, the quality of construction of houses and basic infrastructure was found to be generally poor, and within a few years most houses are beginning to need repair. Often the faulty construction is irremediable. In many cases, houses have poor climatic performance and fail to provide adequate passive ventilation in the warm-humid climate and in contexts where artificial cooling is unaffordable. Houses are often culturally inappropriate: typical cooking with biomass fuel cannot be done in kitchens enclosed within the house, leading households to build additional outdoor kitchens. Poor sanitation is a serious problem in most of the case-study settlements, and in many places it is exacerbated by water-logging or flooding. Only in a few cases, were outdoor communal spaces designed with some care; in most sites sense of ownership was unclear, resulting in untended open areas ending up as waste disposal sites. In most cases, infrastructure provision has lagged behind housing construction, and waste management, street lighting and security, roads and transport, water and electricity were lacking or provided inadequately. It was nonetheless found that communities had great resilience and were making significant efforts in adapting to and transforming their environments. |

Research team: Judith Shaw, Iftekhar

Ahmed (Monash University), Dave Mercer, Martin Mulligan, Yaso Nadarajah

(RMIT Universit), Matthew Clarke (Deakin University).

Reference

|

||

Analysis

| Throughout the length and breadth of post-war Southeast Asia, hosts of peoples were at various times flush with the excitement of post-colonial independence and assertive statehood. Born in the death throes of the Japanese version of Asian nationalism, decolonisation gave birth to a new nationalist mythology that rode across the boundaries of the new states without pause. People were now citizens rather than subjects, and they were formally equal to Europeans. All the new states in which these new citizens lived were concerned with a major exercise of ‘nation building’. This was a versatile concept that often focused on physical or near-physical acts of building the material fabric to fill the hollow shell of the state. Hence, ‘nation building’ focused on building roads, buildings, monuments, factories, industries, armies, economies, and institutions of governance. These activities were often pervaded by a sense of youthful freshness and sometimes by grim determination to achieve. Yet the goal was not a state per se, since that had already materialised in the process of decolonisation. The citizens were encouraged to form bonds with the new state, and accept these bonds as an expression of nationhood—something much more appealing and intimate than the mere accident of living within a national boundary imposed by a former colonial power. This task involved the creation of the emotional and conceptual innards that it was hoped would bind the people to the new polities and to the ruling elites. This two-dimensional bonding was the real heart of the exercise of nation building. Just as there were many variations in the details of the material aspects of this work of creation, so were there in the construction of national communities. Even within the individual nation–states, the national vision of ruling elites moved in different directions at different times. Singapore was a case in point. There, the ruling elite spoke with one voice—at least in public—but the message changed dramatically with the decades. Singapore was unique in the history of Southeast Asian nationalism in that it was not only very late in winning its independence, but its leaders had statehood thrust upon them unwillingly. Singapore’s ruling elite had ridiculed the notion of Singaporean nationhood, having always aspired to living in communion with Malaya-cum-Malaysia. They were scared of a future in which a tiny Chinese-dominated island would be living cheek-by-jowl with giant Malay-cum-Indonesian neighbours. |

The initial calls to nationhood of the 1960s were therefore based squarely on a form of multiracialism that played down the Chineseness of the nation, and played up the contributions of the Eurasian, Malay and Indian minorities who lived and worked alongside the Chinese majority. This remained the case until the late 1970s, but then a dramatic change swept though the young country, driven unambiguously by then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. In a remarkably short space of time, the dominant discourse in building the horizontal bonds of national identity came to centre around a local form of Sino-centric ethno-nationalism, and the non-Chinese minorities (making up nearly one-quarter of the population) were pushed to the margins. This agenda was driven through the school system, beginning in kindergarten, and was implemented in tandem with the intensification of the elitist elements in the education system. Meritocratic elitism had formed a core element in the national ideology and national identity from before the nation’s birth, but from about 1978 it took on a new intensity and seriousness—even as it was being subverted by a racism that was also becoming increasingly overt. The intensification of the elitist education system took the form of systematic upgrades and expansion of kindergarten and school curricula, improvements in the standards of teacher training, improved facilities, and continuous upgrades of expectations in examinations, but it was remarkable that in all these measures, the new resources and the fresh attention to curricula, teacher training, etc. were directed overwhelmingly at Chinese students, while the ordinary needs of non-Chinese children were disregarded with breathtaking audacity. Yet the entrenchment of ‘Chineseness’ (itself a highly constructed and localised identity) in the heart of the national identity was so overwhelming, and the ideological hegemony of the Chinese elite so strong, |

that the racial bias in Singapore’s supposedly meritocratic system passed largely unnoticed and uncommented, at least in public. Even bonus points awarded exclusively to a selection of Chinese children competing for university entry did not warrant comment. Whereas the horizontal bonds of the imagined nation were built around a racial logic, the vertical bonds between the ruled and the rulers were built around an unashamedly elitist logic. The two social visions found a comfortable meeting place in the widespread assumption that the winners in a meritocratic society would be Chinese. The centrality of elitism in Singapore’s national identity meant that in Singapore, more so than in most countries, national identity was built around a core of elite identity. National identity has become difficult to distinguish from the elite identity—a development that was deliberately fostered by the elite itself, but which has burdened the country with unintended consequences. Singapore produces an impressive system of government, but the system is extraordinarily brittle because of the close identification of regime, nation-state and national community. The regime has visited its own insecurities onto the nation via its top-down nation-building efforts. Complaints and criticisms about the government are taken in official circles and implicitly by many of Singaporeans as expressions of disloyalty to the nation, or at the very least of diminishing loyalty. Hence the government monitors closely the feedback it receives about the enthusiasm of Singaporeans in displaying the national flag from their balconies in the lead up to National Day and became seriously concerned when, in the aftermath of the 2001 recession, it discovered that they were showing reluctance, and that even the government’s own grassroots leaders were lukewarm about distributing them. In a country where the regime and the nation are

conceptually almost inseparable, displaying the national flag becomes

a partisan political statement that implicitly endorses the regime.

Such a conflation of national loyalty and political preference is

a conscious squandering and marginalisation of the natural affection

that ordinary people have for their homeland, based on memories and

associations, family, food and familiarity. It is also self-indulgent

and puts the nation-building project at risk in the long term. |

Michael

Barr is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations

in the School of Political and International Studies, Flinders University.

He is the author of Lee Kuan Yew: The Beliefs behind the Man (2000,

2009), Cultural Politics and Asian Values: The Tepid War (2002, 2004),

and (with Zlatko Skrbis as second author) Constructing Singapore:

Elitism, Ethnicity and the Nation-Building Project (2008). |

||

Viewpoint

WRITING REALLY MATTERSFaced with increasing workloads and diminishing resources, academics have to respond to changes in the external environment of universities and to new work practices. Anthony Reid talks about his work practices over a long career and offers some advice to young academics. |

| When did you start in academia? I belonged to a very lucky generation, born at the beginning of World War II, and thus just enough years ahead of the baby boomers of 1945 to teach them as they came to university in the 1960s. The university systems in most western countries were expanding rapidly in the 1960s and ‘70s, Australia’s more than most, and there were jobs for virtually all of us who obtained PhDs at that time. I got mine from Cambridge in 1965, and didn’t have to worry whether there would be a job. It was rather a question of where to go to begin the career. I was doubly lucky in that Australian and New Zealand universities were discovering Southeast Asia at that time, and competing to attract the few specialists on the market. However, because I had written a dissertation in the history of Indonesia and Malaysia without being able to visit those countries, I was more interested in finding a job in that region than taking one in Australia or New Zealand. The University of Malaya in Kuala Lumpur had been recently established as the first university in a new country (Malaya 1957; Malaysia 1963), and I arrived to teach there in mid-1965, a time full of excitement. I have always been grateful for being plunged into the thick of things in that way. I came to ANU five years later, in 1970, when universities in general and Asianists in particular were still in the full flood of expansion. It seemed self-evident that Australia needed to grow and deepen its understanding of Asia, Indonesia in particular. Although there was a lot to be desired in resources and sophistication, it was easy to believe that we were fighting the good fight, moving in the right direction. How have things changed since then? We all know the effects of first the Dawkins reforms that expanded the university system and spread resources very thinly over more than 40 universities, and then the reaction in intensified competition. Older assumptions about lifelong tenure and expanding funding for universities could not co-exist with the post-Dawkins situation, and perhaps the only way out was the competitive, Thatcherite, system of the last two decades. Rather than the sharp and entrenched hierarchy of the American system—wealthy elite institutions at the top and struggling ‘failure factories’ at the bottom—Australia could only re-establish conditions for high quality research through some sort of performance-based competitive research grants. For the young, nimble and ambitious, these conditions can still produce good results. But there are no longer havens where esoteric, demanding research with long-term payoffs can flourish. |

In principle it may be acknowledged that pure and applied research complement each other, but in practice knowledge for its own sake has few defenders in today’s system. In sharp contrast with the United States, moreover, where the best and brightest will do humanities first degrees because the meal ticket degree is a post-graduate qualification in law, medicine or management, the competitive climate in Australia has operated directly on first-degree choice, driving students away from humanities and into disciplines thought (sometimes wrongly) to be more immediately employable. Asian Studies suffered as much as other humanities disciplines from the defection of undergraduate students, and its internal dynamic changed profoundly. Classical studies of all kinds were no longer seen as a ‘good thing’ in civilisational terms, and Asian classics may have suffered even more than Greek and Latin because they are difficult, and because of the unfortunate negatives of Said’s ‘orientalism’. The study of a ‘rising’ Asia must more than ever be a sensible career choice, but it will no longer have the depth of language, literature, or village-level ethnographic study that set the highest standards in my day. The Asianists who thrive in the ‘risen’ Asia will be knowledge brokers rather than creators, moving back and forth between jobs in Asia and the West, riding as well as promoting the integration of Asian and Australian economies. It requires nimbleness and adaptability even more than the esoteric dedication of the older style. Yet still I believe that the stronger institutions that are allowing Australia to play its part in the transformations of our time will be able to protect also some redoubts of purer knowledge, where Tang poetry and old Javanese kekawin are enjoyed for their own sake. Small investments of this sort will disproportionately reward the institutions that will thereby be taken more seriously by our Asian friends. How have you managed to juggle your many activities and maintain your research interests at the same time? The enduring point is that one has to believe that writing really matters, even though its rewards are long-term. We’re justified to put even more effort into it than into the urgent things we have to do every week. Of course it helps to believe in what we’re writing. I didn’t usually find that difficult once into writing, but letting it go for a few months while overwhelmed with other things is always discouraging, and it can be easy then to doubt why we bother, and who is ever going to read it anyway. At those times taking a day off and just digging my way back into it usually worked, and the excitement revived. |

What work habits would you suggest that somebody intent on embarking on an academic career should develop? Most of us find writing such a long-term goal that we endlessly put it off in favour of more immediate tasks.Writing the first page of an article or book project can be a massive hurdle for some; writing the conclusion can seem impossible for others. In practical terms, there is much merit in the recent insistence that we send an abstract of a conference paper before we write it or a summary of a book to a publisher before the book itself. An abstract is in fact a fine way to begin. Increasingly I find this is the way I write—to begin with an idea in the form of an abstract, then gradually fill it out into ever more elaborate outlines. If it’s a seemingly endless book project, I try to have a detailed table of contents always beside me, so it’s a matter of putting empirical flesh on the skeleton of an argument. Academic life is unusually privileged in one respect, that ultimately it is our publications by which we’re judged. This is a terrifyingly solitary responsibility, but it is our own. If I have any advice at all for young academics, it is to treat each setback in other aspects of your career as a chance to write. Each grant we fail to get, each job that goes to someone else, each extra responsibility that does not come our way, can be an opportunity to get something written that will be of permanent value. The readers of what we write, particularly as Asianists, will be far away in space and possibly in time, and will judge us by totally different criteria from those of our immediate colleagues and superiors. That is a blessing given to few professions, and we should make the most of it. What do you consider your major achievements in a long academic career, and why? I’m very happy to have been involved in the beginnings of some important things—Malaysian universities; Southeast Asian Studies at the ANU and later UCLA; the ASAA and its Review; SE Asia Publication Series, and dissertation prize, and finally the Asia Research Institute in Singapore. Clearly, I enjoy new initiatives more than coping with established ones. But in the end it’s what we write that is really our own, as I said, and will remain our own as institutions change. So it is the books to which I would have to point, especially the Age of Commerce*1 volumes for their broader reach, and the two revolution books*2 because they rest on interviews with people most of whom are no longer with us. |

Notes

* Emeritus Professor Reid, Division of Pacific and Asian History at the Australian National University, is a historian of Southeast Asia. A prolific author, he was also founding director of both the UCLA Centre for Southeast Asian Studies in Los Angeles and of the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore. |

||

Women in Asia

| In the past decade, HIV/AIDS has become an increasingly important issue in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and threatens to become a serious regional pandemic that some epidemiologists believe could surpass the levels of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although transmission has been largely concentrated among intravenous drug users, female sex workers and former blood and plasma sellers, it is believed that other modes of transmission, such as commercial and non-commercial homosexual intercourse, non-commercial heterosexual intercourse and mother-to-child-transmission, will all soon be more identifiable as the source of transmission in people testing positive for HIV. While men have made up the majority of those infected to date, as China’s epidemic crosses into the general population, the number of women with the virus will also rapidly increase. Currently, Chinese women face a number of unique vulnerabilities to HIV transmission compared to men. Many of these vulnerabilities are similar to women elsewhere. They are brought on by enabling environments, such as economic, social, cultural and political factors that fuel HIV transmission, as well as the gender roles assigned both to men and women that influence male/female sexual aggression and passivity, promiscuity and ideas surrounding the level of a person’s ‘acceptable’ sexual and reproductive health knowledge. Women’s heightened vulnerability to HIV transmission is largely the result of the interplay between the unequal status accorded many women due to their sex, their disempowered status within society, unequal gender-based power relations both within the domestic and public arenas, and the patriarchal norms and attitudes that influence all of the above. However, there are also country-specific vulnerabilities in China that have resulted from the privileged status accorded to Chinese men, particularly in sexual relationships, |

the rise of son-preference as a result of the introduction of the One Child Policy and the gender imbalance and associated problems this has caused. Thus, there are significant gender-based factors increasing Chinese women’s vulnerability to HIV transmission in the PRC that must be considered when responding to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Many of the identified vulnerabilities to HIV transmission Chinese women face are directly related to the reality that gender equality has not yet been achieved in China. There are also a range of factors in China which have been proven elsewhere to be conducive to high rates of HIV transmission. These factors include: low levels of STI/HIV awareness and condom use; the lack of a nation-wide comprehensive sex education curriculum that provides STI/HIV prevention information to young people prior to their first sexual encounter; very low levels of self-perceived risk of contracting an STI/HIV; and increasing levels of STIs among the general population, demonstrating the prevalence of unprotected sexual intercourse with multiple partners. Chinese women are also under-represented politically, limiting their opportunities to initiate policies and regulations that will improve their status. However, the status of Chinese women is widely diverse, and there are clear divisions between the rural and urban areas, with women in urban areas generally faring much better than their rural counterparts. In addition, disparity in education levels can dictate a woman’s future direction, with those who are more educated being able to pursue greater opportunities than the less educated. Education opportunities in urban areas again far outweigh those available to women in the rural areas. Further heightening women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS has been the slow response to the unfolding epidemic by the Chinese government and health authorities. |

For many years, the epidemic was fuelled by outdated views on HIV/AIDS responses, reinforced by problematic laws and legislation that contributed to an environment of stigma and discrimination against people living with HIV/AIDS. While the government has made positive steps to reverse these trends, a lot of work still needs to be done before effective measures are fully enacted. In addition, the government’s reluctance to fully cooperate with civil society and provide adequate funding to projects run by inter-governmental organisations, non-governmental organisations and international non-governmental organisations are major factors that continue to cripple China’s response to HIV/AIDS. Therefore, until the Chinese government allows the full incorporation of civil society into all aspects of prevention and treatment, any real progress in HIV/AIDS prevention is delayed. Consequently, when determining Chinese women’s vulnerability to HIV transmission, the unequal status of many women combined with the privileged position accorded to men strongly indicates that women face a heightened vulnerability to HIV transmission. These vulnerabilities are closely linked to issues of disempowerment and unequal gender-based power relations. They also mean that women face unique threats to their human security, not only because of their vulnerabilities to HIV transmission, but also because of the effects these threats have on their economic, food, health, personal, community and political security. With HIV/AIDS recognised as a major threat to human security worldwide, and distinct gendered differences in human insecurity identified, it is imperative that human security discourse becomes inclusive of a gendered perspective—in both its mainstream discourse and approach to security, and in the mainstream policy documents produced by organisations such as the United Nations and the Commission on Human Security. |

Dr

Hayes is a lecturer in International Relations in the School of

Humanities and Communication at the University of Southern Queensland.

She is also a member of the Public Memory Research Centre (USQ) and

researching the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region

and how minority nationalities within Xinjiang are being disproportionately

affected by HIV/AIDS. |

||

Indonesian Studies

| Now in its 27th year, the conference attracted more than 300 people from academia, government, NGOs and the business community from Australia, Indonesia and the United States. The conference theme reflected 2009 as ‘the year of voting frequently’, with elections for parliaments and heads of government at all levels, culminating in the re-election of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono in July. The year also marked the 10th anniversary of Indonesia’s first democratic election in the post-Soeharto era. The conference addressed six topics: Voters and the New Indonesian Democracy; Organising Democracy; Society and the Electoral Press; Parties and Parliament; Women in Politics; and Local Election Case Studies.

R William Liddle, Professor of Political Science at the Ohio State University, discussed the high public support for democracy in Indonesia, as well as public attitudes in general. Surveys by the Indonesian Survey Institute over the election periods of 1999, 2004 and 2009 found that people thought the national economy was doing well. In 2004, the main public support was for leaders and political parties, Liddle said, and in 2009 for the quality of the economy. For the next five-year period of 2009, the aims were for a more stable and effective government. However, President Yudhoyono would have passed two terms by 2014 and therefore not be eligible for re-election. The weak party system would need improvement before then to ensure that any difficulties surrounding election of a new leader were avoided. Adam Schmidt, from the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, Jakarta, described the 2009 elections as ‘the worst in the reformasi period’, due to the change of legal framework in 2008 and the change to the electoral system. |

This combined with poor training of electoral and polling booth staff and a general lack of competitiveness in the national election body raised the most concerning political issues. However, these were mainly administrative problems, and there was increasing support for a fair election process by parties and public alike, as shown by the peaceful pre-election climate. Support for a fair election process was further demonstrated by Dr Ian Wilson (Murdoch University) in his presentation on ‘preman’ (gangster) roles in politics. Political thuggery was increasingly being regarded as a redundant way to win elections, Wilson said, with the popularity of charismatic party leaders becoming more sought as an avenue to victory. In his presentation Associate Professor Ariel Heryanto (ANU) focused on the participation of disadvantaged social groups in the 2009 election campaigns, comparing these campaigns with elections under the authoritarian rule of the New Order.

Sugiarto’s paper noted that the internal organisation of parties still had shortcomings, but the main concern was the remaining presence of money politics on all levels of hierarchy. The charisma and popularity of leaders was still an important factor on the local as well as the national level. Although the application of more advanced strategies and political communication techniques had made a difference in campaigning, said Sugiarto, in reality there had been very little progress in the transformation of policy. The structural shortcomings of the parliamentary system were further discussed by Stephen Sherlock in a post-election context. Problems like a consensus vote (as opposed to majority vote—which the vast majority of democratic countries use), lack of verbatim transcripts and limited capacity for individual dissent fostered an atmosphere of difficulty around progress in parliament and a lack of transparency of proceedings. This, said Sherlock, made for a closed and convoluted process that was conducive to corruption, and also because there was no monitoring of the legislative process. |

Dr Sharon Bessell (ANU) commented on the role of women in politics, and particularly the lack of progress, in a comparative international context. Even though counteractive measures had been introduced, the domestic ideology of women prevalent in the New Order had continued into the new millennium. A 30 per cent quota of women candidates for parties had been largely ignored, said Bessell, and no party had been able, or even wanted to, uphold the numbers. Expanding on these points Hana Satriyo (The Asia Foundation) illustrated the lack of female presence in regional elections. The total number of candidates was less than 5 per cent in all levels of hierarchy. To overcome these problems, said Satriyo, more conducive conditions and positive attitudes towards women in positions of power were needed to create opportunities and bring women’s representation to a more balanced equilibrium. Two regional case studies brought the primary topics of political structure and election matters into context. Blair Palmer (World Bank, Jakarta) highlighted the prevalence of peaceful pre-election conditions in his paper on Aceh. Partai Aceh won a landslide victory in the regional elections, using the Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding and Peace for Aceh as the basis for its campaign. Despite violence and intimidation in the lead-up to the campaign, this did not greatly influence the outcome. Although corruption was still evident, Palmer said the way the elections were carried out was seen to be a success, especially since peace was a main priority, at least in the short term.

Indonesia Update was convened by Edward Aspinall and Marcus Meitzner. The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies will publish the conference papers in the Indonesia Assessment series, in early 2010. |

Karina Bontes Forward is a student

of Asian Studies (Indonesian) and Environmental Policy at the Australian

National University. |

||

UNDOING SUHARTO'S NEW ORDERKathryn Robinson responds to a challenging question that goes to the heart of gender relations in Indonesia. |

|

The book argues that the Suharto regime imposed an ideologically driven set of gender relations that instantiated paternal authority on the diverse gender orders of the Indonesian archipelago, which has afforded differing forms of power and authority to men and women alike. The ideological agenda of the authoritarian New Order mirrored that of other regimes that used a model of patriarchal authority in the family as a ‘natural’ model of authority in society and the state (so Suharto himself was the father of the nation, or Bapak Pembangunan—the father of development). Responding to Professor Spyer’s challenging question, I argued that the seeds of the New Order’s unraveling, at least in regard to its ‘gender agenda’ were in its own economic and related social policies. The economy was opened up to work under Suharto, |

but the foreign factories that entered wanted young female labour, not the labour of the men who the state designated as heads of households and breadwinners. When Indonesia sought to capitalise on its abundance of cheap labour in an increasingly interlinked global economy, the demand was for female housemaids not male construction workers. Several decades of population control through ‘Family Planning’ program have inevitably changed the way women and men express their sexuality, in ways not intended by the architects of the policies. The book argues that when Suharto fell, in a manner similar to a passing colonial regime (as discussed in Hamzah Alavi’s now classic article), the effective control of opposition meant there was no obvious contender to capture the strong state, so we have seen a lot of jockeying and contestation among groups asserting rival claims. Some of these groups have represented strands of political Islam, and in many cases they have grabbed onto gender relations as a tool for seeking power, through the passage of local purportedly sharia-based legislation that seems to focus principally on control of womens’ bodies and freedom of movement; or populist campaigns such as the one promoting the anti-pornography law, which again most notably targeted women’s freedom of action. So gender relations is continuing to be a field of political struggle, related to the exercise of power in general, not just relation between men as a group and women as a group. |

Professor Raewyn Connell, who is Australia’s most internationally recognised gender theorist, has noted that this book is the first to bring a gender relations perspective to an analysis of Indonesia. The book’s argument is grounded in historical and anthropological perspectives: I use historical materials to challenge the oft-stated assumption that claims for gender equity is a Western ideology imposed on the Third World. Indonesian women have been active in international feminist activism, including the World Conferences on Women, since colonial times. Current Indonesian feminist activism makes significant contributions to global discourses on gender equity under the rubric of Islamic feminism. Anthropological perspectives highlight the diversity of patterns of gender relation throughout the archipelago that were not completely submerged under New Order gender activism. The book does not provide a total answer to Professor Spyer’s question, but it does present a view of a long-established and dynamic movement for gender equity in Indonesia that has been embraced by women and men. In the book, I frequently return to field data form the mining town of Sorowako in South Sulawesi province, where I have conducted fieldwork for 30 years. This long-term witnessing of the unveiling of novel forms of Indonesian modernity provides a touchstone for the arguments that I make on a more national, or even global, level. |

Kathryn Robinson is

Professor of Anthropology at The Australian National University’s

College of Asia and the Pacific, and is President of the Asian Studies

Association of Australia. |

||

OPPORTUNITY FOR STUDENTS TO DO VILLAGE RESEARCH IN JAVA |

| Fifty years ago, 37 anthropology and sociology undergraduates from Bandung’s Universitas Padjajaran (UNPAD) and Yogyakarta’s Universitas Gadjah Mada (UGM) were sent to 37 different villages throughout Java to collect data for their final-year thesis (skripsi). Under the supervision of the late Dr Mervyn Jaspan, they collected data on all aspects of village life, including economics, education, religion, social structure, demography and politics. They were given identical instructions so their data lent itself to comparative analysis.

‘It is appropriate for these villages now to be re-surveyed to examine what social change has occurred over the last 50 years,’ Witton said. “However, I’m not in any position to carry out this research. I’ve therefore been contacting sociology and antropology lecturers at UNPAD and UGM and have suggested that, under their supervision, their undergraduates could each re-study one village as part of their final-year research assignment. Dr Witton reports he has already received heartening replies from lecturers and their students and the project now seems likely to go ahead. In addition, he has been contacted by scholars in Indonesia and other countries, who are carrying out village studies on Java and are interested in perhaps including some of the 37 original villages in their studies. ‘I would especially welcome hearing from Indonesian sociology and anthropology lecturers who would like to have their students re-study those villages,’ he said. ‘However, I will be happy to hear from anyone else who has an interest in this evolving project’. |

Art and Culture

|

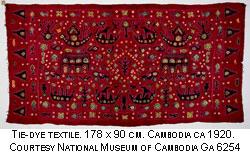

Cambodia and central Java are 2000 kilometres apart, and their inhabitants' ethnicities and textile traditions quite different. So it is intriguing that two textiles—a cotton batik sarong from Pekalongan, a north central Java coastal town, and a silk textile patterned by tie-dye resist in the collection of the National Museum of Cambodia—share a remarkably similar pictorial composition. Both textiles are at least 80 years old and feature particular motifs derived from modernist themes. Batik-patterned cloth has been made in Java for centuries. Patterns on court batiks are traditionally conservative, but from the mid-19th century boldly innovative patterns began to appear. These are termed generically batik belanda (‘Dutch batik’).They were created in workshops set up by women with Dutch or Chinese ancestry living in Java. Towns along the north Java coast celebrated for batik belanda production included Pekalongan, Lasem and Semarang. These women entrepreneurs responded to the changing milieu of 19th century coastal Southeast Asia, producing these new designs. Postcards, European books and magazines, posters and photographs in circulation provided a rich source of imagery representing the cutting edge of innovation at the time. Themes included European-style floral designs and fairy tales, public events, depictions of local military campaigns, and card games. Of particular interest, however, is another distinctive group of themes which depict modern developments in technology. These featured commercial buildings, trains, ships and airplane services, cars and bicycles—all impressive manifestations of modernity. Batik belanda were worn by women in sarong style—that is stitched into a tube shape and folded and tucked in at the front. They were also fashioned into pants style for men. Batik lengths were used as a baby or goods carriers, and as a veiling head cover (kudung) in Sumatra and Malaysia. Moving to the mainland and to Cambodia, some 50 tie-dye patterned textiles comprise the majority of the textiles remaining in the collection of the National Museum of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. |

The Khmer language word for these textiles is kiet, which corresponds functionally to the Indonesian terms for the tie-dye resist patterning techniques of plangi and tritik. They were prepared from lengths of imported Chinese-sourced, machine-woven silk and dyed with synthetic dyes. About half have patterns based on geometrically arranged motifs of stars and flowers. The other half of this collection, however, has pictorial—that is, identifiable—motifs reflecting modernity. These include architectural structures such as shop houses, and cottages built in the Chinese style, sited directly on the ground, not raised Khmer-style on stilts; bicycles; cars; ships of several kinds; and flat bed trucks. From this minimal number of examples there is clearly a remarkable concurrence of pictorial motifs between Javanese batik belanda with ‘technological’ motifs and these Cambodian tie-dyed textiles. But in contrast to the observed uses of batik belinda, the absence of any information about the uses of the tie-dyed, pictorial textiles (which would not be used as headscarves) is perplexing. There is evidence for the production of tie-dye silk textiles on the Northeast Malay Peninsula. Winstead describes in detail the skill of tie-dyers in Trengganu, these local craftswomen said to have learned the techniques from Boyanese living there (1925:66). Significantly, Hill notes that ‘…Kain pelangi [tie-dyed textiles] are produced [in Trengganu]. The patterns are rather crude and resemble some of those produced by batek (sic) work on fabrics seen in Malaya’ (1949:84). This observation concerning the connection between batik belanda and pictorial tie-dyed silk textiles in the National Museum of Cambodia collection presents two key questions. Firstly, by what route did batik belanda or knowledge of these textiles reach Cambodia, where the batik technique is not practised, and secondly what was the context that supported production of these novel, non-traditional patterns on silk. To address the first question, there are at least two possible physical routes. The first involves lively intra-regional maritime trade in the mainland Southeast Asia region with goods, including batik sourced in Javanese markets. Arab merchants, the Hadhramis in particular, were very active in centres on the north Java coast. Veldhuisen mentions that:

Not only did Arab merchants trade in batik along

the east coast of Sumatra and in Singapore, but their networks also

connected with other Hadhramis along the Northeast Malay Peninsula.

|

For example there was a Hadhrami presence in Trennganu. ’… a Hadhrami known as Tokku Tuan Besar (1794–1878) [was] the son of a grain merchant from Java, who settled in Trengganu in the late eighteenth century‘ (Othman 1997:88). In the adjoining province ’Arabs of Hadhrami descent contributed to the running of the religious administration in neighbouring Kelantan’ (Othman 1997:89). The second proposition is that batik skills and batik itself were transmitted by Javanese workers and their families who migrated to Sumatra and Trengganu from the mid-19th century onwards (De Klerk 1938: 422). This circumstantial evidence argues for the likely presence of batik, including lengths with modernist themes, in Trennganu and possibly Kelantan. Both these Northeast Malay Peninsula provinces are in close contact with Cambodia geographically, economically and culturally through their Malay affinity. In Cambodia there are two groups who adhere to the Islamic faith—Cham and Malays. Cham, though fine weavers, are not recorded as making tie-dye cloth. Silk headscarves have a veiling function for Muslim, but not Khmer, women, but pictorial tie-dye patterned textiles are inappropriate as headcloths. Is it possible that Malay women in Trennganu and/or in Cambodia crafted the museum collection? Though with this evidence it is possible to propose who the makers of these tie-dye textiles were, the reason why pictorial tie-dyes, equivalent in theme to batik belanda, were created is not apparent. There is, however, one early 20th century initiative which could have fostered innovation in Cambodia. George Groslier, who set up the Royal School of Arts in Phnom Penh in 1918, recruited craftworkers from the king’s court to this newly instituted school. His aim was to keep Cambodian craft skills alive by producing items of interest for sale to tourists, to French residents and for exhibition and sale at international exhibitions abroad. The sales were mediated by a local French arm of government, Corporations Cambodgiennes, whose brief was to market the items crafted at the school both locally and abroad. This is a context that could have provided the impetus for designing innovative textile patterns, such as those seen on the pictorial tie-dyes, by those who had the skills to produce them. The rationale for their manufacture accorded with French entrepreneurial ambitions for the territories they administered in Southeast Asia in the early 20th century. |

|

| Gillian

Green M.Phil, MA, is an Honorary Associate in the Department of

Art History and Film Studies, University of Sydney. Her research interest

covers Southeast Asian textiles with a special emphasis on the traditional

textiles of Cambodia References

|

|||

POST-DOI MOI ARTISTS IN VIETNAMArt historian Annette van den Bosch is one of a handful of scholars who have started to open up the new research field of post-war Vietnamese art. Here she looks at the work of three post-Doi Moi* () artists. |

|||

| There was significant maturation in the work of some Vietnamese artists after 2000. The context for their work changed from the late 1990s, as new galleries opened in Vietnam’s main cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City. Artists sold work and travelled abroad, international artists and writers visited Vietnam, and the National Museum of Fine Arts began to exhibit a wider range of contemporary artists. Very little contemporary Vietnamese painting and sculpture is collected by any Australian collection, and the only contemporary collection is at the Queensland Gallery of Modern Art, GOMA. Lê Thua Tien is from Hue and lectures at the Hue College of Arts. Nguyen Thanh Son is from Pleiku and works in Tây Nguyen and Ho Chi Minh City. Dang Anh Tuan is from Hanoi and works in Tây Nguyen. The three artists reached mid-career in their professions in 2000 when exhibition and market opportunities expanded. These artists draw on the architectural heritage and intangible cultural heritage of central Vietnam to create their artworks.

A central theme in Lê Thua Tin’s artwork is the impact of colonialism, globalisation and cultural destruction in Vietnamese contemporary and heritage culture. He illuminated the intersection of heritage or tradition through creating more contemporary interpretations and practices. Tien creates paintings on do paper, the traditional rice paper of Vietnam, and lacquer, a traditional form that became a fine art form in the art schools of the French colonial period. His Unsent Letters series used do paper on painting surfaces to create a weathered appearance. He also introduced the use of shadow text and erasure to create ambiguity. In Untitled (2003), Tien exploits the effect of shadows to create sculptural relief in stonework or raised calligraphy. The use of text and textural effects are characteristic of all his works. |

In the Reflection Series (2006–07), Lê Thua Tien developed quite radical ways of working in lacquer using marble dust, sand from the river, old bronze relics or textiles found on abandoned sites, or timber from destroyed old buildings. Tien’s contemporary use of the traditional lacquer medium enables him to develop paintings which have the density of sculptural objects and the patina of heritage artefacts. The Reflection Series drew inspiration from the mirrors and glass paintings in the tombs of the Nguyen Lords, and the use of water as phong thuy in the pagodas. The instability of light, shadow and reflection is presented as a metaphor for the Buddhist concept of existence and non-existence. Reflection also refers to the artist’s introspection on his life and heritage. The artists Nguyen Thanh Son and Dang Anh are successful contemporary artists whose work creates powerful imagery of new cultural formations in which inter-ethnic forms are fused. They re-imagine concepts of cultural identity as more heterogeneous. The concepts that these artists employ are not the same as earlier representations which aimed to gloss over ethnic antagonisms and to promote allegiances adopted during the three Indochina wars from 1945 to 1979. Nguyen Thanh Son and Dang Anh Tuan draw their inspiration from the burial rituals, the sculpture of the nha mo, burial tombs and ceremonies of the Djarai and Bahnar peoples of Tây Nguyên. These artists demonstrate respect for the specific cultural rites of the Djarai and Bahnar groups with whom they have sustained relationships over years. Nguyen Thanh Son’s portraits of individual elders are compassionate and honest depictions of age and hardship as well as wisdom. A good example is the painting, Innermost Feelings (2007) which was included in the Post-Doi Moi exhibition, Singapore Art Museum (2008). The Holiness of Land and Man (2003), and The Journey of Yin Yang (1997), are earlier paintings which portrayed the elders in relation to their ancient cultural symbols. The composition of these paintings successfully portrays almost life-size figurative portraits in designs that include sculptural figures and symbols. |

Another group of Son’s paintings, Exposition (2002), Nude and Sacred Land (2002), and Nude and Mask (2002), introduce sacred totems, the Chorao bird and the Gecko. Other totemic objects depicted in Son’s compositions are masks and earthenware urns, used with reference to the practice of fertility rituals. The figures in these earlier compositions are drawn from the sculpture on the nha mo so that the people and life forms are absorbed into their ancestors rather than presented as distinct individuals. Son’s painting design became more complex over this period in a way that carved wood designs and weaving patterns were used to create surface texture across the canvas. His composition became more layered and off-centre. Dang Anh Tuan also draws his inspiration from the imagery of the nha mo and the natural environment of the Tây Nguyen. The painting Family (2004) is not conventional portraiture. His imagery expresses profound feelings, even agony.

The paintings from the Highland Impression series refer not only to distance and change in the central highlands but to the artists’ own artistic journey. Highland Impression 4 (2004) resolves the elements of imagery from Tây Nguyen into an overall design. Tuan’s paintings create new formal compositions that merge sculptural and tomb shapes, minority totems such as the gecko, the darkness of night in the highlands, or firelight effects into the overall painting design. The use of strong colour contrasts and mixed media builds a tactile surface that replicates the natural materials and space of the Djarai and Bahnar environment, drawing attention to their culture and place in contemporary Vietnam. Nguyen Thanh Son and Dang Anh Tuan represent in their artworks a profound understanding of the link between biodiversity and cultural diversity in Tây Nguyên. Their imagery displays greater maturity in intercultural concepts of cultural identity than that produced throughout the conflicts and ideological struggles of 20th century Vietnam. |

|

| * The Vietnamese government’s economic

reforms announced in 1986 were otherwise known as Doi Moi.

Dr Van den Bosch is an Adjunct Research Fellow at Monash Asia Institute. She will be publishing an article in the Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society, in Autumn 2009 on 'Professional Artists in Vietnam: Intellectual Property and economic and cultural sustainability'. Recent Papers on Vietnamese Art History

|

|||

Student of the month

Obituary

A CHINESE SCHOLAR-GENTLEMAN: LIU TS'UN-YAN (1917-2009) |

|

To give one small example. In 1952, Liu Ts'un-yan wrote a couple of short essays, reminiscences of Cheng Yanqiu, the famous Opera actor he had known in Beijing in the late 1920s. In the second essay, Liu Ts'un-yan remarks in passing that the foundation of this great performing artist's success lay in his lifelong pursuit of Taoist self-cultivation, including the practice of tai chi, and of breathing techniques. This, done steadily and consistently over the years, was what maintained the high standard of his singing. This profound observation, lightly made, reflected Professor Liu's everyday thinking and informed his conversation. Liu Ts'un-yan’s lifelong involvement with Taoist philosophy and religion, a subject on which he became one of the world's unrivalled authorities, had arisen directly out of a personal experience during his childhood in Peking. He was a sickly child, and no physician, Chinese or Western, could be found to help him mend his health. He was finally taken to a Taoist monastery and there he was taken in hand by one of the monks. That was when he started learning some of the basic qigong practices that helped him in a very practical way throughout his long life. Liu Ts'un-yan was so many things at one and the same time. He was a Chinese scholar-gentleman at home in many branches of Chinese literature, classical and vernacular, and in many varieties of the Chinese language—Mandarin, Cantonese, Shanghai dialect, even Shandong. Shandong was his family's ancestral home. And yet for centuries his family had been Chinese Bannermen, honorary Manchus, inheritors of that proud tradition within a tradition. He was the most meticulous scholar and teacher, able to rise to the demands of the most exacting textual scholarship, at home in the most arcane byways of the Confucian, Taoist and Buddhist classics. His scholarship was founded not on ideology or theory, but on close, indefatigable reading of central texts. He was a painstaking bibliographer, making copious notes wherever he went, at libraries all over the world. And yet behind this scholarly (and sometimes daunting) persona, was a man of great humanity and warmth, a playful man of letters, a witty essayist (again in both classical and colloquial Chinese), a fluent novelist and playwright. Liu could be a devastating critic, wherever he discerned incompetence and pretentious, phony scholarship. And yet he was a prodigiously kind and generous mentor if he sensed the presence of a receptive mind. |

It was Australia's extraordinary good fortune that in the early 1960s Liu Ts'un-yan chose to leave Hong Kong and join the ANU. He made Canberra his home for the last half of his life. Over the subsequent decades did more than anyone to put the ANU on the world map of Chinese Studies. His deeply humanistic vision of Chinese Studies was spelled out most eloquently in his own inaugural lecture, delivered on October 5, 1966: I quote: What students of Chinese are learning appears to be an instrument. But it is an instrument only in the sense that it is a medium through which advanced studies in much broader fields may be made. A mere knowledge of the language does not in fact constitute the real understanding of that language. In order to understand the feelings expressed in the Chinese language one must be acquainted with at least some of the many rich works of literature which have been written in Chinese... We are concerned not only with a language and a literature but, through the learning of that language and literature, with something more lasting, a deeper, and hence more intimate and even sympathetic, understanding of the people whose language and literature we are studying. Professor Liu was happy and proud during the past three years to see for himself that this humanistic legacy of his was being taken seriously once more, that traditional Chinese Studies were being revived, and that the ANU was once more taking the lead and standing up for these enduring values. All his life he had, in his own writings, in his own teaching, in his own person, embodied the very things we are striving to put back at the centre of our curriculum: a sense of cultural continuity and actuality, of the past in the present, and of the present in the past; a sense of the interconnectedness of literature, history and philosophy, of the lively links between scholarship and life. Liu Ts'un-yan was bearer of a great tradition. As his own stature grew, he himself went on to become one of the key members of a worldwide circle of great scholars and critics, many of whom were his personal friends. He saw such friendships as pools of light in the darkening times around him. The very idea of friendship, friendship of kindred spirits, of like-minded scholars and men of letters working together across the boundaries of geography and language, indeed of time itself, the notion that all of this was a force for good lay at the heart of everything he did. In a short casual essay republished in China in 2001, he ascribed to the perennial philosophy of China a crucial role as mediator in a chaotic and materialistic age. But when he said this, he was referring to hard-won truths, to genuine wisdom, not to the facile pressing into service of Taoism for political ends, of which he took a very dim view. More and more with the passing of the years he spoke with utter simplicity of the need to distinguish between what was genuine and what was false. In the end, he insisted many times, this was all that really mattered. Liu Ts'un-yan's passing leaves us bereft of an irreplaceable voice, a voice speaking quietly but eloquently for China in all of its power and glory, in all of its triumphs and failings, at a time when the importance of such a true understanding of China is greater than ever. |

| John Minford Professor Minford is professor of Chinese and head of the China Centre at the Australian National University. This is an abridged version of the speech which he delivered at Professor Liu's funeral on August 14, 2009. |

|

Recent Interesting Books on Asia

|

Contributed by Sally Burdon This selection includes recent books by ASAA members

Laura Dales and Barbara Hatley. As these are ASAA publications, special

member prices apply. If you are a member please check the ASAA

website for more details—if you are not yet a member you

might like to join and take advantage of these and other benefits.

|

|

|

Laura Dales xiii + 151pp, notes, bibliography, index, Routledge, London, 2009, ASAA Women in Asia Publications Series, ISBN 9780415459419. $215 In contemporary Japan there is much ambivalence about women's roles, and the term 'feminism' is not widely recognised or considered relevant. Nonetheless, as this book shows, there is a flourishing feminist movement. The book investigates the features and effects of feminism in non-government women's groups, government-run women's centres and the individual activities of feminists Haruka Yoko and Kitahara Minori.

Barbara Hatley Colour and black and white photographic illustrations, xvii + 336pp, notes, bibliography, index, paperback, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2008, ASAA Southeast Asia Publications Series, ISBN 9789971694104. $49.95 During the dramatic economic and social transformation of late 20th century Indonesia, theatre performances in Central Java featured a familiar cast of rulers, nobles, clown servants and ordinary people. However, these presentations were not a repetition of age-old cultural traditions. Instead, by stretching the framework of Javanese theatrical convention, theatre troupes challenged dominant cultural and political values. As political pressures intensified in the final months of the New Order regime, their witty, critical performances drew enthusiastic, oppositionist crowds.

Gavin W Jones, Chee Heng Leng and Maznah Mohamad (eds) xvi + 322 pages, index, hardback, ISEAS, Singapore, 2009, ISBN 9789812308740. $64.95 ‘This is an excellent and rare exploration of a sensitive religious issue from many perspectives: legal, cultural and political. The case studies from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand portray the important and exciting, yet very difficult, negotiation of Islamic teachings in the changing realities of Southeast Asia, home to the majority of Muslims in the world. Interreligious marriage is an important indicator of good relations between communities in religiously diverse countries. This book will also be of great interest to students and scholars of religious pluralism in a Southeast Asian context, which has not been studied adequately.’—Zainal Abidin Bagir, Executive Director, Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies (CRCS), Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia". |

James A Millward Maps, black and white illustrations and photographic illustrations, xix + 440 pages, index, bibliography, appendix, paperback. University Presses of California, Columbia and Princeton United States. 2009, ISBN 9780231139250. $46.95 This is the first comprehensive history of Xinjiang. Drawing on primary sources in several Asian and European languages, Millward presents a thorough study of Xinjiang's history and people from antiquity to the present and takes a balanced look at the position of Turkic Muslims within the People’s Republic of China today. While offering fresh material and perspectives for specialists, this engaging survey of Xinjiang's rich environmental, cultural, and ethno-political heritage is also written for travellers, students, and anyone eager to learn about this vital connector between East and West.

Andrew Ranard Colour photographs, xv + 368 pages, index, bibliography, notes, dustjacket, Silkworm Books, Thailand 2009, ISBN 9789749511763. $158.85 This is the first comprehensive history of Burmese painting, from 11th century Pagan to the present, including over 175 painters and more than 300 photographs. The book explores the historical transformations of the art, with psychological interpretations of major artists, the legends which followed them, and analysis of their oeuvres.

Tan Ta Sen Colour and black and white photographic illustrations, xi + 291 pages, index, bibliography, paperback, ISEAS, Singapore, 2009, ISBN: 9789812308375. $89.95 ‘Tan Ta Sen's book on Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia is not the first one on the subject, but it is the first book that puts Cheng Ho's voyages in the larger context of "culture contact" in China and beyond. He has garnered numerous sources, from published documents to architectural sites and buildings, to support his arguments. He has done much more than previous scholars writing on this subject’— Professor Leo Suryadinata, Chinese Heritage Centre (Singapore). |

|

NEW BOOKS FROM THE ASAA SERIES Thailand and T’ai Lands: Modern Tai

Community Kampung, Islam and State in Urban Java Workers and Intellectuals: NGOs, Trade Unions

and the Indonesian Labour Movement Javanese Performances on an Indonesian Stage:

Celebrating Culture, Embracing Change Kuala Lumpur and Putrajaya: Negotiating Urban Space in Malaysia Gender Islam and Democracy in Indonesia Gender and Labour in Korea and Japan: Sexing Class Feminist Movements in Contemporary Japan Sex, Love and Feminism in the Asia Pacific Young Women in Japan: Transitions to Adulthood Gender, State and Social Power in Indonesia Women, Islam and Everyday Life: Renegotiating Polygamy in

Indonesia Books can be ordered through Asia Bookroom. |

|

Awards and grants

| INDONESIAN ADDED

TO FULBRIGHT LIST AWARDS AND GRANTS FOR THE STUDY OF JAPAN NLA JAPAN FELLOWSHIP |

Positions vacant

|

JOB WEBSITES These sites offer career prospects for graduates and postgraduate in Asian Studies. If you know of other useful sites advertising jobs for postgrads in Asian Studies, please send them to allan.sharp@homemail.com.au. http://www.jobs.ac.uk and http://www.acu.ac.uk/adverts/jobs/ advertise worldwide academic posts. http://isanet.ccit.arizona.edu/employment.html is a free-to-access website run by The International Studies Association. http://www.reliefweb.int is a free service run by the United Nations to recruit for NGO jobs. http://www.aboutus.org/DevelopmentEx.com has a paid subscription service providing access to jobs worldwide in the international development industry. http://h-net.org/jobs is a US-based site with a worldwide scope. Asia-related jobs (mostly academic) come up most weeks. http://www.aasianst.org/ is the website of the Association for Asian Studies. New job listings are posted on the first and third Monday of each month. You must be a current AAS member to view job listings. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/. The Times Higher Education Supplement. http://www.comminit.com/ is the site of The Communication Initiative Network. The site includes listings of jobs, consultants, requests for proposals, events, trainings, and books, journals, and videos for sale related to all development issues and strategies. You can view all posts on these pages without registering, but will need to register to post your items. |

Diary dates

| TRADE AND INDUSTRY IN ASIA PACIFIC: HISTORY, TRENDS AND PROSPECTS, ARC Asia Pacific Futures Research Network 2009 Signature Event, Canberra, 19–20 November 2009. The conference will be held at The Australian National University in partnership with La Trobe University. It will explore the regional and global market integration in trade and industry in Asia Pacific in the context of major changes in the global economy and its historical, institutional and political economy aspects. Online registration open now. JAPAN: DESCENDING ASIAN GIANT? workshop, Adelaide, 23–24 November 2009, organised by the Japan–Korea node of the Asia Pacific Futures Research Network. Professor J A A Stockwin, University of Oxford, will chair and facilitate the workshop for postgraduates and early career researchers at the University of Adelaide. Ten to 15 speakers from Australia, Asia, Europe and the United States will discuss aspects of contemporary Japanese economy, politics, society, demography and international relations. MEETING THE MILLENNIUM DEVELOPMENT GOALS: OLD PROBLEMS, NEW CHALLENGES, conference, Melbourne, 30 November–1 December 2009. Organised by the Australian Council for International Development and Institute for Human Security, La Trobe University, the conference will critically engage the Millennium Development Goals and the processes or rather possibilities for change. A key aim is to bring together development practitioners, academics, policy makers and the business community. For more information, see the conference website. GENDER AND OCCUPATIONS AND INTERVENTIONS

IN THE ASIA PACIFIC, 1945–2009, workshop, Wollongong, 10–11

December 2009. Sponsored by the Asia Pacific Futures Research

Network, CAPSTRANS and the Faculty of Arts at the University of Wollongong,

this small workshop, at the University of Wollongong, will bring together

for the first time established scholars, ECRs, postgraduates and community

members and activists to discuss issues related to gender, occupation

and intervention. A few competitive places for sponsored positions

(travel within Australia only and accommodation for two nights) for

postgraduates and ECRs are available. See the workshop

website for more information or contact the organisers: Dr

Rowena Ward or Dr Christine de

Matos. |