Current Affairs

| In 2006, a new political development took place in Vietnam when pro-democracy activists, labour leaders, religious freedom advocates and other dissidents coalesced into an identifiable national network known as Bloc 8406. Previously, political and religious freedom advocates acted individually or in small cliques isolated from each other. On 8 April 2006 one hundred and eighteen activists issued a manifesto that called on the government to respect basic human rights and religious freedom and to permit citizens to freely associate and form their own political parties. This agenda was the result of growing cross-fertilisation among advocacy groups. Members of Bloc 8406 wanted to publicise their cause in advance of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit to be held in Hanoi at the end of the year while world attention was focused on Vietnam. Bloc 8406 takes its name from the date of its manifesto. Bloc 8406 represents a diverse network of professionals widely dispersed throughout the country. Among the signers of the manifesto were teachers and lecturers (31%), Catholic priests (14%), university professors (13%), writers (7%), medical doctors (6%), intellectuals, engineers, nurses, Hoa Hao religious leaders, businessmen, army veterans, technicians, ordinary citizens and a lawyer. Bloc 8406 was predominately an urban-centred network, with over half the signatories residing in Hue (38%) and Saigon/Ho Chi Minh City (15%), with additional concentrations in Hai Phong, Hanoi, Da Nang, and Can Tho. Bloc 8406 represented a direct challenge to the political legitimacy of Vietnam’s one-party state. In late 2006 and continuing in 2007–08 security forces rounded up key leaders, summarily tried them in court and sentenced them to imprisonment. It appeared that Bloc 8406’s leadership had been effectively decapitated and Vietnam’s network democracy snuffed out. This judgment was premature. Pro-democracy activists continued to press for political, civil and religious rights through the internet, blog sites and contact with overseas Vietnamese pro-democracy political parties. Once again security authorities swung into action and in 2009 arrested an estimated 30 more political activists. Seventeen activists were put on trial and convicted between October and February 2010. Vietnam’s renewed crackdown on political dissent in some respects represented a mopping up operation of remnants of Bloc 8406. But in another important respect it reflected the state’s draconian response to challenges posed by the emergence of a new breed of political activists. In previous years, political dissidents focused their protests on freedom of expression, association and religious belief. |

In 2009, political activists expanded their reform agenda to include environmental issues raised by the award of a bauxite-mining contract to a Chinese business corporation, corruption by senior officials, the government’s handling of the global financial crisis, political and diplomatic relations with China, and other issues. This expanded political agenda opened a new front

in challenges to the legitimacy of the Vietnamese state. Whereas previous

political dissidents focused on the regime’s claim to rational-legal

legitimacy, the new breed of dissidents now challenged the regime’s

legitimacy based on economic performance and nationalism. This represented

a serious threat to the authority of the party-state as a growing

anti-China backlash spread In May–July 2009, Vietnamese public security officials rounded up seven political dissidents who were part of a loose pro-democracy network; most were associated with the Vietnam Democratic Party. The state used its control of the media to conduct an orchestrated campaign of denigration and vilification. On 19 August, five defendants appeared on state television with their heads bowed and publicly admitted to ‘undermining and overthrowing the Vietnamese state’. The following day the state media triumphantly reported that the dissidents had ‘plead guilty and begged for leniency’. In October 2009, security officials bundled together the cases of nine political dissidents and conducted perfunctory trials in Hanoi and Haiphong. All defendants were found guilty under Article 88 of the Penal Code that made it a crime to conduct propaganda against the state. The defendants were sentenced from two to six years’ imprisonment plus an additional two-three years under house arrest. Three of those convicted had hung banners over highway overpasses in Hanoi and Haiphong calling for democracy and criticising China. |

In December, public security officials indicted five of the previously convicted dissidents on new charges under Article 79 of the Penal Code relating to the overthrow of the socialist state. The maximum penalty for conviction was death by firing squad. Separate trials were held in Thai Binh and Hanoi in late December and January. Once again the legal proceedings were perfunctory. One dissident who recanted his confession and alleged police coercion was sentenced to 16 years in prison. A second defendant who refused to plead guilty was sentenced to seven years. The two who confessed were sentenced five years in prison. Upon release all five face between three to five years under house arrest. Since then two further trials have been conducted. Writer Pham Thanh Nghien was sentenced to four years in prison under Article 88 in January, and writer Tran Khai Thanh Thuy was sentenced to three and a half years on charges of assault in February. In 2009, Vietnamese officials faced a new challenge to their authority, political commentary written by bloggers on the internet who had no discernable connection to the pro-democracy activist network. In early 2009 a group of 700 individuals signed up to a Facebook site to promote their opposition to bauxite mining. Later in the year security officials blocked Facebook and imposed restrictions on Twitter and YouTube. Additionally, four prominent bloggers were detained and questioned about their internet sites where they posted commentary criticising Vietnam’s handling of relations with China, bauxite mining, and land disputes between the Catholic Church and the state. Vietnam’s one-party state rests on multiple sources of legitimacy (rational-legal, performance and nationalism). In 2009, it faced a widening of the challenges to its legitimacy as dissidents, political activists and bloggers criticised the government for its handling bauxite mining, corruption and relations with China, thus challenging each base of regime legitimacy. The state responded predictably by reverting to it

default mode of repression, arguing it was acting on rational-legal

grounds under the Penal Code. The current challenges to regime legitimacy

in Vietnam have opened up new fissures among the elite in Vietnamese

society. The next year will be a crucial testing ground as Vietnam

prepares for its 11th national party congress scheduled for January

2011.

|

|

Carlyle A. Thayer is Professor of Politics, The University of New South Wales at the Australian Defence Force Academy. |

||

| Beset by increasing terrorism, tensions with neighbouring India and the consequences of years of dictatorial rule, economic turmoil and political instability, it is time the Pakistan’s leaders received a wake-up call and worked to help the country fulfill its destiny, writes Hammaad Qayyum Khan. If Islam means ‘peace’ and Pakistan stands for, ’the land of the pure’, most Pakistanis are not living a life, but a paradox. Given the current grim realities, there is little that can help build a ‘softer image’ of the country. Many might wonder how a land of such gifted individuals can be governed as it is. There are a few important reasons for this. First, internal harmony is hard to find, especially on most of the important issues and second, the role of the international allies, most notably the United States. Today the situation is ripe for every actor involved to further their agenda. The current wave of blasts and suicide attacks, in the words of author and activist Naomi Klein, could be termed as ‘clearing the canvas’. The country is still facing the bitter fruits of ‘controlled democracy’, especially during the last years under General Musharraf. The desperate youth, fed up of years of dictatorial rule, economic turmoil, political instability, radicalisation and polarisation within the society, are a possible easy prey—fodder for the war.

The situation on the Indian front is not conducive to achieving this. India, for example, is reported to have resumed work on the controversial Kishanganga hydro-power project and has taken up another four mega projects in Indian-held Kashmir that can result in major water shortages in Pakistan. Other examples—be it the tragic Mumbai incident or the recent statement by Indian Army Chief General Deepak Kapoor that the Indian army was ready to face Pakistan and China at the same time, or the more recent Shiv Sena’s hitting out at Bollywood superstar Shahrukh Khan for backing Pakistani players in the Indian Premier League—bring to mind the words of Indira Gandhi, who once famously said, ’You can't shake hands with a clenched fist’. |

The elusive handshake is vital, not just in the context of bilateral ties between the nuclear-armed neighbours, but also for achieving much-needed peace and stability in war-trodden Afghanistan. Under the current circumstances it is important to ask how long relations between Pakistan and India will remain hostage to extremist elements. People in both countries await a thaw in relations, because if this situation persists they will continue to lose out to the extremists. In Afghanistan, Pakistan would most likely like to see a limit to India’s growing presence in the international effort to achieve a settlement with Taliban moderates. Finding a solution to the violence in the tribal areas will not be easy, but political integration of these areas with the rest of the country is indispensable for stability in the long run. US Defence Secretary Robert Gates admitted in an article for a Pakistani newspaper last month that when the Soviet Union left the region, the US decision to largely abandon Afghanistan and cut off defense ties with Pakistan was a grave mistake, driven by some well-intentioned but short-sighted US legislative and policy decisions. Commenting on Gates’ India–Pakistan visit, Pakistani journalist Talat Hussain accused the United States of employing ’both-edges-of-the-mouth diplomacy’, and said the United States did not want to let go of any lever of pressure that could be applied to keep Islamabad’s behaviour in check. Use of the Indian card as a tool of coercive diplomacy, and non-recognition of Islamabad’s long-term interests in Afghanistan, Talat added, would limit Pakistan’s ability to become the staging-ground for a successful bid for peace in Afghanistan. Talat underlined that in Pakistan’s desire to see non-hostile borders with Afghanistan and India lay the key to building consensus on a lasting peace for Afghanistan and, most importantly, that this desire should not be seen by the ’powerful world capitals as a sinister plot to keep the Taliban in Afghanistan’s power play’. Pakistan Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, speaking at Oxford University earlier this year, underscored Pakistan’s contribution in the war on terror and maintained that ’All the coalition forces put together in Afghanistan have not had as many casualties as we had. The economic cost of this conflict to Pakistan has been over US$35 billion’. There are two views regarding President Obama’s Afghan Surge. The more cynical is that the idea of a withdrawal from Afghanistan beginning in mid-2011 and the complete withdrawal from Iraq by the end of that year will provide the Obama administration with a pedestal from which to win back the support of the anti-war group. |

McChrystal’s Senior Adviser in Afghanistan, David Kilcullen, wrote in Small Wars Journal that ’unilateral strikes against targets inside Pakistan, whatever other purpose they might serve, have an unarguably and entirely negative effect on Pakistani stability. They increase the number and radicalism of Pakistanis who support extremism, and thus undermine the key strategic program of building a willing and capable partner in Pakistan’. Jonathan Manes, a legal fellow with the American Civil Liberties Union National Security Project, was reported as saying that the American public had a right to know whether the drone program was consistent with international law, and that all efforts were made to minimise the loss of innocent lives. After three American soldiers were killed by a roadside bomb in Pakistan's border region recently, The Guardian’s Declan Walsh rightly pointed out that ’to many Pakistanis the most shocking aspect of the bombing was not the death toll, or the injuries inflicted on survivors, but the question that it raised: what was a team of American soldiers doing in a tense corner of North West Frontier province?’ For the people of Pakistan there is no escaping the situation without confronting it. Sixty-two years on, we sons of an insensible nation, the slaves to our own ‘destiny’ are not at war with anyone but ourselves and our lies. It’s time we pleaded guilty. We have better people to represent Islam and Pakistan to the world. Islam is too great a religion and Pakistan far too beautiful a country to be left to those who do not understand the meanings of either of them. Pakistan’s hopes breathe with the resolve of an independent judiciary, passionate youth and a small but robust civil society. Those at the helm of Pakistan’s affairs need a wake-up call. With more discipline, greater numbers of honest professionals in every field and strong democratic institutions that elusive peace can be obtained. |

| Hammaad Qayyum Khan is a PhD candidate at the Centre for Arab and Islamic Studies, The Australian National University |

||

| Broadly speaking, Indonesians isolated abroad after the political changes in 1965 fell into three categories: most were students or teachers; some were diplomats and staff in Indonesian missions; and a smaller number were members of official delegations travelling overseas, such as politicians and cultural workers. One thriving element of Indonesia’s diplomatic engagement with the world was through educational exchanges and cultural visits. Perhaps the best-known program was that funded by the Ford Foundation from 1957, when promising young economists were provided with scholarships to study in the United States, notably at the University of California, Berkeley. Hence the sobriquet the ‘Berkeley mafia’ given to such scholars when it was to them that the New Order turned after 1966 for its development policy. Less is known about those Indonesians who schooled in the eastern bloc. By 1965, about 2,000 Indonesians—more than any other foreign nationality—were studying in the Soviet Union, with about 600 in regular university programs and the remainder in a variety of military or party colleges or other programs. Indonesians were also despatched to China, often due to their party connections, to teach Indonesian language and studies in Chinese tertiary institutions. While the majority of Indonesians studying abroad were in Russia or China, smaller numbers went elsewhere in the eastern bloc.

Those members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) who were abroad attempted to establish a structure for the party-in-exile. The senior-most PKI figure outside of Indonesia was the Secretary of the Central Committee and member of the Political Bureau, Jusuf Adjitorop, in Beijing, who claimed that he had received the Central Committee’s delegated authority on 22 February 1966 to lead the party overseas. As Suharto asserted his control, Indonesian diplomats appointed by former president Sukarno were recalled to Jakarta. Diplomatic casualties of Indonesia’s dramatic volte face after 1965 included relations with the USSR. As the split widened in the international communist movement between the Soviets and the Chinese, |

the PKI had favoured Beijing, a trend which continued partly (though not entirely) because the PKI leadership, the ‘Delegation’ under Jusuf Adjitorop, was housed in Beijing. In January 1967, the Soviet Embassy in Beijing was put under siege by Red Guards, with armed clashes on their common border breaking out in March and August 1969, revealing the extent of the polarisation. Given the PKI’s inclination to Beijing, those Indonesians in the USSR who chose not to adopt the Soviet line began to feel Moscow’s cold shoulder. They moved out of the Soviet Union in increasing numbers, either to Albania or direct to China. Albania occupied a rather unique position in the Sino-Soviet split. Despite its physical proximity to Moscow, it nonetheless sided with Beijing, and after the 1965 change in Jakarta, it provided refuge to pro-China PKI cadres from elsewhere in Eastern Europe who sought to leave the USSR or the Soviet satellites. During 1966–76, when China underwent the Cultural Revolution, Indonesian exiles were isolated from the general Chinese population. The broader social dislocation in China meant schools closed and employed exiles lost their positions. By the mid-1980s the world was changing rapidly. When Chinese Foreign Minister Wu Xueqian came to Jakarta in April 1985 it was clear that the PKI exiles were the sole lingering hurdle to the normalisation of political relations with Indonesia, frozen since 1967. Wu reportedly told journalists, ‘the Chinese Communist Party no longer sends congratulations on the anniversary of the PKI. PKI members who fled to China now are old and ill, and no longer active.’ With the exception of about a half a dozen, most of the hundreds of Indonesian exiles that had formerly taken refuge in China had departed, or were encouraged by the Chinese to do so, thus smoothing the way for the normalisation of diplomatic relations on 8 August 1990. As Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of Perestroika took hold in the former USSR from about 1986 the rise of Russian nationalism fanned racist attacks on foreigners, particularly Asians or Africans. The spirit of communist solidarity had faded, and many of those Indonesian exiles who had lived in the USSR for decades chose to move to the West, getting residence in Holland. In November 1989 the Berlin Wall, symbol of the divided city and the bipolar world, was opened and then pulled down. The Cold War had ended. With the exception of small handfuls of Indonesians, living either in families with their local spouses and offspring, or as individuals supported by small state pensions in their old age, the exiles have long since gravitated to the West, mainly Holland or France, or in a few cases even returned to their homeland, albeit holding a foreign passport. Most Indonesian exiles—numbers remain hard to discern, but may have peaked at around 500, now reduced by attrition and time to about half that—now live |

in the Netherlands, with other substantial populations in France, and scattered across Belgium, Germany, Sweden, and with about half a dozen still living in China, under very spartan conditions. Many have experienced lives of great difficulty, unable to take advantage of their particular training and expertise. The exiles formed no unified political bloc and presented no solid resistance to either the New Order or subsequent governments in Indonesia. Many became active in the politics of their host countries. But most struggled to find their feet, and had to concentrate their time and effort on establishing a livelihood to provide for their families and their old age. The years of exile during the 1960s and the flight from the countries of initial refuge in the Communist bloc to their final asylum in Western Europe undermined rather than strengthened their ideological solidarity. The politics of exile—particularly in China, but also in Vietnam, for example—fractured the party and eroded the bonds of party loyalty. While the exiles may still share their sense of a common past, and resent their treatment by the Indonesian government, they are unified more in their collective grieving for the dead amongst them rather than by any ideological commitment or party loyalty, a point noted powerfully by both the artist Basuki Resobowo (c.1917-99) in some of his paintings and by the essayist Hersri Setiawan in his writings on exile. There are associations, formal and informal, of exiles, coalescing around particular individuals or groups. These are often based on shared experiences or the desire to keep alive aspects of their Indonesian identity, its literature or culture; but these remain essentially social rather than political. These networks clearly cross state boundaries; the exiles in Holland are in close contact with those in neighbouring countries and, for example, phone regularly to keep up with news and developments. But whatever shared identity exists as Indonesian exiles—and there is a common rage against the injustice of successive the Indonesian governments—it would appear less cohesive and more complex with each relocation, each change in country of refuge over the decades. Key issues for the exiles remain the pragmatic ones of residence: should they remain abroad in their host country, or return in their old age to Indonesia, accepting the overtures of the post-Suharto governments that they will be safe. Some take the opportunity to visit with their foreign passports. Few have accepted the offer to regain their Indonesian citizenship, and their intense resentment at living, and dying, away from their homeland runs deep. So long as the 1966 parliamentary decree (TAP MPRS No. 25/1966) banning ‘Communism/Marxism/Leninism’ remains in place they fear a hostile government may again victimise them. As a matter of principle, many feel the Indonesian government should not only offer to issue them with new passports, but also to acknowledge its guilt in abandoning them abroad and to apologise. For most, the years abroad have driven a wedge between their experiences, their identity, and that of their homeland. It is not a gap that can be bridged simply by an Indonesian passport. |

| David T. Hill is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies in the School of Social Sciences and Humanities at Murdoch University. This article is based on a presentation to the Humanities Research Centre at the Australian National University on 13 November 2009. |

||

Conservation

| Doi Mae Salong in Thailand’s Chiang Rai Province is an unusual and counter-intuitive case of landscape management. The Doi Mae Salong watershed feeds into the Mae Chan River, a tributary of the Mekong. The area is classified as a Class 1 watershed, which requires a high degree of protection and limited human use. The area is controlled by the Royal Thai Armed Forces (RTAF) as part of a military reserve area. This status arises from its sensitivity in security terms, both because of its proximity to the Myanmar border and as a legacy of the conflict between the military and communist insurgents during the 1970s. There are several similar military reserve areas in northeast Thailand. Despite its protected status the area is highly populated. The population includes remnants and descendants of Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang forces who fled to Burma after the Chinese revolution and later moved to Doi Mae Salong, where they were granted residency in return for assisting the armed forces against the insurgents. These ex-Kuomintang are now heavily involved in agriculture and tourism. There are also members of other ethnic groups, including Akha, Lisu, Lahu, Shan and Yao, and a significant number of refugees from Myanmar. Doi Mae Salong is seriously deforested. There are areas of natural forest, particularly on hilltops, all part of a complex mosaic of agricultural plots (especially areas under shifting cultivation) and coffee and fruit tree plantations. The contrast between an area with protected status and a population involved in technically illegal agricultural activities is not uncommon in northern Thailand. What is unique is the fact that the RTAF is engaged in a process of participatory multi-stakeholder landscape management. In 2007 the RTAF initiated a reforestation project in honour of the King’s 80th birthday. The first efforts followed a classic command-and-control approach. Tree planting work began on deforested hilltops and slopes. However, these areas were already used for agriculture, leading to loud protests. What happened next was surprising. The RTAF responded by rethinking its approach rather than enforcing decisions already made and approached the Asia Regional Office of IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, in Bangkok, for advice about more realistic approaches to conservation. As a result, a multi-stakeholder, land-use planning approach was developed, involving villagers, Tambon leaders and officials from various government agencies, such as Tambons, the Land Development Office, and the Watershed Conservation and Management Unit, and NGOs. The project area is the watershed core area, an area of 90 square kilometres—the total watershed area is 335 square kilometres—occupied by about 15,000 people. |

It includes several villages and the town of Doi Mae Salong, a busy market and tourist centre with numerous restaurants, tea and coffee shops and guesthouses and hotels. IUCN became involved in the landscape because it seemed to fit neatly with a major IUCN program, the Livelihoods and Landscape Strategy (LLS), which is being tested in selected landscapes in over 20 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The LLS approach is based on the idea that conservation and livelihoods objectives can best be managed on a landscape scale, with multiple land-use types being balanced according to conservation and social objectives. This differs from many traditional approaches to integrating conservation and development in that meeting livelihoods is not seen as a way of achieving conservation, but as an essential function of ecosystems. The approach avoids centralised planning and focuses on the importance of negotiations and trade-offs between stakeholders around land uses. An example of negotiated land use is the case of farming on sites highly subject to erosion, such as slopes and hill tops. In such cases negotiations occur about providing alternative farming land in valleys. These negotiations seem to be quite genuine and allow for genuine choice. Another somewhat radical approach is the planting of perennial fruit trees and cash crops (tea and coffee) in sites susceptible to erosion. Although these species perform watershed protection functions, conventional forest department practice would insist on the planting of forest species. Perennial cash crops meet both conservation and livelihood objectives. Forest landscape restoration is undertaken with the assistance of the Forest Restoration Research Unit at Chiang Mai University, which focuses on re-establishing natural forest species and the Royal Project, under the patronage of the King, which focuses on income generating agroforestry species practices. The project, through the activities of NGOs, provides support for the testing and demonstration of integrated farming methods. |

The striking thing about Doi Mae Salong is not the various conservation and agricultural practices that are being tested and implemented but the way land-use decisions are made. It is too early to measure identifiable improvements in livelihoods, but there is strong evidence that decisions are being made differently. Informal surveys of local people suggest fairly widespread knowledge of the new arrangements and that people are confident that the RTAF is serious about the approach. A rising level of trust is evident. Although there is no formal land title and, given the political realities around protected areas in Thailand, no likelihood of reform in the foreseeable future, there seems to be a fair degree of confidence about future security of access to agricultural land and resources. People do not feel their land will be removed. The RTAF commander at Doi Mae Salong, Brigadier General Chaluay—promoted for his work at Doi Mae Salong—describes his assignment as the most difficult of his military career. In the past he was just used to giving orders, but now he feels trusted and relaxed. This highlights the paradox. How can a military organisation, entirely predicated on hierarchy, command and control, operate in a significantly participatory way? There is no similar example of the National Parks Department of the Royal Forest Department operating like this. It is important to note that there has been some tradition of military involvement in development activities and community forestry in Thailand, largely in connection with dealing with people relocated from sensitive security areas in the past and, perhaps, with a ’hearts-and-minds’ approach. Another possibility is that the RTAF is not locked into pre-ordained ways of ’doing’ conservation, since army personnel do not see themselves as conservation experts. |

|

Dr

Fisher is a Senior Lecturer (human geography) in Geosciences

at the University of Sydney and an advisor to IUCN’s Livelihoods

and Landscapes Strategy. Tawatchai

Rattnasorn is IUCN’s field coordinator for Doi Mae Salong.

The LLS Program is funded by DGIS, the Development Agency of the Ministry

of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands. |

||

Media

|

During the analog period of the 1980s and early 90s, when video technology began thriving among Indonesia’s new middle class, the authoritarian government took anticipative measures, such as censorship and taxes on sales and screenings, to contain and control video-related practices1. The experience of the 1998 political uprising showed activists mobilising the power of video and the internet to effect socio-political changes. Still fresh in public memory is footage of the shootings of Trisakti University students in Jakarta, repeatedly aired by every television station after the event and circulated internationally within hours. These images sparked sentiments of national solidarity, leading to mass student protests in several cities across Indonesia denouncing the New Order regime. At the same time, under the umbrella of the anti-New Order movement, online communication such as chat rooms and mailing lists flourished as organising spaces and forums for discussion that could circumvent militaristic state repression2. Post-Suharto Indonesia saw an increase in media production and distribution, both commercial and non-profit. With regional areas gaining more autonomy; increasing consumption of cable television, computers, the internet and mobile phones; and growing numbers of local stations, calls for information decentralisation and democratisation became widespread. From activist perspectives, these changes were perceived as having the potential to foster participation and broaden the social-change agenda through the autonomous production of content. Video cameras were now small enough to carry around and cheap enough to be a realistic purchase for both collectives and individuals. Citizen media, Indonesia-style, had been unleashed. The current state and future possibilities of activist video distribution channels in the Indonesian context is a complex web of multiple models. Even while they address the challenges of off-line distribution methodologies, video activist organisations such as Forum Lenteng, Kampung Halaman, and EngageMedia are simultaneously engaging with the possibilities of internet-based distribution. Independent initiatives are burgeoning. Whether the responsibility of distribution is assumed by the video-makers themselves, supported by festivals, screenings or exhibitions, based on commercial opportunities, or developed through existing websites, the challenges are significant. |

The problems of online distribution are inseparable from debates about licensing, and are also linked to the challenges of technological infrastructure and access. But undeniably, in this period of rapid technological development, the activists’ tools of video and internet are converging. As the transition from off-line to online distribution of video content occurs, several creative organisations, such as the ones below, are showing remarkable initiative. Formed in 2003, Forum Lenteng became committed to engaging youth with experimental video techniques and developing audio-visual research methods. Based in the outskirts of Jakarta, Forum Lenteng works largely with communities located at the peripheries of urban centres, such as Jakarta and Padang, to produce video-based information about their lives and share it on the internet.

The project of AkuMassa, for example, encourages participants to embed their video in a dedicated blog and to add comments and notes, generating discussion of the issues raised. Such a platform places society as much more than a subject or an audience, showcasing video stories from a range of local contexts. While Forum Lenteng emerged from Jakarta’s contemporary art scene, for many projects the roles of artist and activist coincide. Artists are seen as facilitators, and video art is viewed as an opportunity to experiment with the distribution of socio-political content as much as to play with the medium itself. |

Kampung

Halaman Kampung Halaman also holds screenings in other villages,

often followed by public discussions about issues highlighted in the

videos. The videos produced by such communities are understood as

part of a process of self-empowerment through which interaction and

education can lead to social transformation. EngageMedia originates in Australia but now also has bases in Jakarta and Yogyakarta. The primary focus of its activities is its video-sharing site. All videos on the site use Creative Commons licensing to encourage downloading for off-line redistribution.

A key goal of the organisation is to explore how online distribution can work in low-bandwidth situations. EngageMedia has set up a series of local archives using plumi, an open source video-sharing platform. The archives run on a server hosted locally in the organisation’s office, allowing rapid uploading and downloading to the archive. Anyone on the local area network can watch videos and easily copy them to USB sticks, DVDs and CDs. This provides all the benefits of a database and digital storage and the participating organisations can increase their technical skills and become ’online ready’ as bandwidth improves. |

Alexandra

Crosby is Events Coordinator for EngageMedia and a writer, researcher,

designer and arts worker committed to developing relationships between

communities. She has worked with a wide range of groups and individuals,

particularly in Indonesia and Australia, on creative approaches to

environmental issues such as forest and water management. She is completing

a PhD on the visual culture of activist communities in Java.

|

||

| The old fiction ’Southeast Asia as a region’ (invented by the Cold-War imperatives and its Southeast Asian studies apparatuses) has increasingly become a reality, thanks to the unprecedented growth of intra-Asia pop cultural flows. But in most writings in English ’intra-Asia’ pop cultural flows narrowly refer to the Korean Wave and J-Pop. Seriously missing in these analyses are two major alternative streams. The first is those works with strongly Islamic content, and the other is a range of pop cultural forms (music, films, drama series, dance) which are heavily indebted to Bollywood. Sometimes the latter two are mixed. The popularity of the Indonesian film Ayat-ayat Cinta (Verses of Love) is an illustration of what Pop Islam may look like. When released in 2008, the film broke a new record for ticket sales, surpassing any title of any genre in the country, including Hollywood blockbusters. The film was also well received in Malaysia and Singapore. This was one of the first Indonesian films to feature a female protagonist who is nearly fully veiled. Many considered it as one of the most Islamic films. A polygamous marriage that features in the film heightened the already intense controversy on the new campaigns for polygamy. Since 1990 Islam has enjoyed unprecedented political clout in Indonesia, despite being continually prone to internal division. Islam's success has not come without problems. Inequality in the distribution of the fruits of the recent ascendancy has gone unabated. Many Muslims and non-Muslims alike continue to suffer from economic marginalisation. Their frustration helped the recruitment for militia groups for various actions, some using Islam jihad as a rallying cry. However, since the mid-1980s a growing number of urban-based and well-educated Muslims have occupied high-level political as well as economic positions. They have a greater need and ability to justify and celebrate their newly acquired privileges, and to express their identities. Like the new bourgeoisie elsewhere, Indonesian new-rich Muslims have a new-found preoccupation with lifestyle, display of wealth, and exuberant consumption. |

Against such a background the success of Ayat-ayat Cinta can be appreciated. In a different but related development, analysts of dangdut music have similarly argued: only after undergoing a major gentrification the folk music dangdut and Bollywood movies have become widely popular among the Indonesian middle classes. The film Ayat-ayat Cinta is based on a best-selling novel by Habiburrahman El Shirazy. The story is set in Egypt, with background music and scenes that are markedly Islamic throughout the film. It centres on the love story of Aisha (a rich German citizen of Turkish descent) and her schoolmate from Indonesia, Fahri, who has a modest economic background. Going to the movies in Indonesia, as elsewhere, often means more than a feast for the sight and hearing, or simple relaxation. It also allows a moment of reflection on what life might look like in a different and better world than one’s own day-to-day reality. Indonesian films often project and promote a particular utopia of a modern and prosperous Indonesia in the image of the liberal and secular West. Until recently, veiled women could hardly find a space in such cinematic utopias, let alone central representation. Off screen, by the early 1990s female veiling was already incorporated into a major boutique fashion industry. Veiling articulates new prosperity, high cultural taste and cosmopolitan beauty that complement, and occasionally overtly substitute for, religious piety, self-restraint from worldly pleasure, or sexual chastity. In Ayat-ayat Cinta, Aisha well fits the image of a wealthy and beautiful female Muslim seen in the many glossy magazines in contemporary Indonesia, or who frequent shopping malls in major cities. My analysis of Ayat-ayat Cinta suggests that the film (more than the novel) problematises the general and largely conservative view of Islam that prevails in Indonesia. It does so subtly and moderately, and with compromises that contradict the more liberal perspectives of Islam in Indonesia. The familiar and convenient dichotomy between traditional/modern or conservative/progressive Islam is highly problematic. Ayat-ayat Cinta does not choose to play safe by reaffirming the status quo, or by seeking to please the more conservative majority of its potential audience for political or commercial gain. |

One reason for Ayat-ayat Cinta's popularity lies precisely in its being both more and less than Islamic. It is hybrid in substance and style. Despite its richly and markedly Islamic elements, in many sections the film resembles features of Hollywood and Bollywood movies, as well as Indonesian television dramas (sinetron). In contrast to the female characters in veils, the economically disadvantaged male protagonist Fahri wears Western-style casual clothes and a trendy haircut. He does not grow a beard or wear a skull cap. In his wedding ceremony Fahri wears a Western business suit and tie. The scenes of the wedding itself are redolent of those in Bollywood movies. These more-and-less-than purely Middle Eastern Islamic elements, and more importantly the H/Bollywood-cum-sinetron elements, struck a chord with the urban youths. Amid the fervour of Islamisation, the significance of this hybridity is easily lost. In the disorienting moment of post-authoritarianism and secular liberalisation, the release of Ayat-ayat Cinta cannot be better timed. It offers an attractive and much-needed middle ground or alternative between the persona of the young militant Muslim with technological weapons and that of the old-fashioned, provincial and orthodox Muslim. In the protagonist Fahri, young Indonesian Muslims find an attractive blend of the attributes of a pious Muslim—a member of the young middle-class intelligentsia, and a post-colonial Indonesian citizen who is at ease with the world of classical Islamic texts, as well as a Western-dominated global lifestyle. Young Muslims were drawn to Ayat-ayat Cinta for the pleasure of discovering their aspired selves for the first time on the big cinema screen. Their preferred self was publicly recognised with respect and authoritatively legitimised by such a powerful institution as the film industry in the grand and glittering shopping mall. This film represents a long overdue alternative to the standard popular cultural products full of explicit sex scenes, violence and what critics see as superstition in mainstream print media, television and cinema. |

Ariel Heryanto is Associate Professor of Indonesian Studies, School of Culture, History and Language, the Australian National University, and Head of the Southeast Asia Centre. |

||

Art and Culture

| Courage and the Aesthetic

Chen Chieh-jen, a conceptual artist filmed his performance, On Going 2006 in an abandoned factory in which he slowly moves bundles of leaflets or newsletters, and fire extinguishers to a pile beside an old truck. Inside the truck canopy are hung large black and white media portraits of dead comrades from the period of martial law 1949-1987. In a glass office an old television plays news footage from the Cold War period, while a modern vehicle which slowly enters the factory is plastered with signs calling for Taiwan to become the 51st state of the United States. The gloomy interior of industrial colours, grey, dark green and blue is briefly lit by the contrasting modern car and signage but no contact is made between the actors. Instead, Chen Chieh-jen pulls out a box from the truck and sets up a small silk screen set to print a left manifesto. Finally, the old truck is reversed to the edge of the screen. Throughout the performance these scenes are contrasted with sequences from the central atrium of a vacant office block in which the camera surveys empty windows and walkways. The conflict of ideologies, the sense of suspended time and place enforce the viewers feeling of fascination and futility. The Cold War, the growth of China and globalisation and their effects on the invisible people of Taiwan are evoked by the artist. Yao Jui-Chung’s major group of black and white photographs, Everything will fall into ruin 1990-2009, explores the aesthetic of ruin in Taiwan, creating evidence of the social dislocation resulting from shifting political, military and economic priorities. Sculptures of fallen buddhas, decaying traditional houses, abandoned factories, military installations and a deserted theme park are grouped in a sequence which reiterates the impact of militarisation, colonisation and rapid social and economic change throughout the Taiwanese islands. Chen Chieh-jen and Yao Jui-Chung illuminate the others’ work and update earlier Taiwanese critiques of colonialism and generational conflict shown in APT 2, 1996, by Wu Tien-Chang, who reworked old photographs to critique and caricature stereoptypes. Rural displacement and urban contradictions Some of the most critical and complex works are from the People’s Republic of China. Chen Quilin (b. 1975) lives and works in Chengdu, documenting the loss and change of earlier habitations and ways of life. APT 6 includes an installation that required the remarkable transportation and erection of three traditional houses, Xinsheng Town no. 275-277, from a town flooded by the Three Gorges Dam project. The physicality and scale of the two-storey houses complete with sleeping lofts and an exterior cooking space impresses with the authenticity of the reconstruction as well as the tangible memorial to a lost way of life. The re-erected houses, as art, signify their lost site and foreground issues for contemporary site-specific art raised by Miwon Kwon, (One Place After Another: Site Specific Art and Locational Identity, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. 2000, p.46). This work also reminds the audience of a work by Yin Xiuzhen, Beijing, 1999 (APT 3 2002), an installation of a timber structure, traditional roof tiles, and photographs used to signify the destruction of the old courtyard houses of Beijing. |

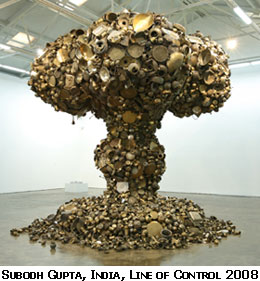

Chen Quilin’s other work in APT 6 is a video, Garden 2007, which creates memorable images of vivid bunches of peonies or dahlias carried by flower-sellers through the dark winding alleys of the old town, to the multi-storey houses and apartments of the nouveau riche, so familiar in their ornate vulgarity. The flowers, and their mobile sellers provide striking contrasts with their surrounds, even when the sellers take to the water in boats. The overwhelming impression on the viewer is of the destruction of the old and construction of the new in the traversed city. Qui Anxiong (b. 1972 in Chengdu) also uses poetic imagery to make a contemporary critical two-part video. His drawing, based on traditional Chinese techniques is animated in the videos titled, The new book of mountains and seas 2006-09. Qui Anxiong draws on a classic tale of geography and mythology to enchant through fantastic creatures, hybrid creations that enable him to critique through the inclusion of contemporary images and issues. Some of the contentious issues in China which he depicted are human-organ farming, industrialised animal farming, and the damming of the Yangtze River for the Three Gorges Dam. The contradictions of the 20th century world are explored as well through the depiction of warfare, environmental destruction and bio-engineering. Yang Shaobin (b. 1963), whose work, X-Blind Spot 2008, critiques the mining practices in Hebei and Shanxi Provinces, and Inner Mongolia, in a series of paintings, a monumental sculpture of the heroic worker in fiberglass, and a waxwork- realism worker propped against the wall. The title works on several levels, the paintings are phosphorescent, the blind spot refers to the limit on the miners’ sightlines underground, and the frequent deaths and accidents in mines in China which are often not reported. X-Blind Spot 2008 was developed as a collaborative project with the Long March group some of whom were exhibited in APT 5 in 2006. The works of Chinese artists exhibited at APT 5 and 6 demonstrate the critical re-casting of history and focus on the impact of economic and social change by artists from China, which makes their work so dynamic and relevant to a more globalised art audience. Negotiating boundaries and ideologies Subodh Gupta (b.1964) from India presented the strongest contemporary art installations. Line of Control (1) 2008 was a massive construction 500 x 500 x 500cm that established a powerful presence. The disputed Kashmir border region between India and Pakistan (the line of control) is a focus for fear of renewed nuclear conflict. Subodh Gupta constructed a nuclear cloud on a metal armature covered in discarded brass utensils of all kinds. The resonance of the battered brassware was of the rubbish dump and the destructive waste that pollutes our environment. The nuclear cloud had a tangible presence as it dwarfed the audience, making a bold statement about potential destruction and its impact on domestic life and people. |

Kyungah Ham (b.1966) of the Republic of South Korea also used images of the nuclear cloud in Nagasaki Mushroom Cloud, Hiroshima Mushroom Cloud 2008. The difference was in scale and process and her use of her art to negotiate the boundaries between South and North Korea. These textile works from Kyungah Ham’s 2008 exhibition, ‘Such Game,’ were sent as composite imagery and photomontages to be embroidered in the Democratic Peoples’ Republic of Korea via intermediaries in the Peoples Republic of China. The project began as a process for opening up communication with North Koreans about local anxieties and foreign politics that influence everyday lives on both sides of the border. Although some work was confiscated and others returned in sections she was able to assemble enough textiles for her exhibition, two of which were presented in APT 6. The re-embroidering of these media images by people whose existence has been marred by the occupation of the Korean peninsula by Japan until 1945, the loss of Korean lives in camps in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, and the subsequent division of Korea as cold war proxy, is profound. Kyungah Ham’s artwork also reconfirms the significance of feminist and activist art by South Korean artists. Kibong Rhee (b. 1957) also from South Korea showed a wonderful installation, There is no place-Shallow cuts 2008. A small willow tree is obscured by a moving veil of mist from an artificial fog machine which the viewer observes behind a glass wall in an empty darkened enclosed space. Rhee’s installation makes the viewer consider the natural world, in a heightened poetic form drawing on the traditional significance of the willow in East Asian culture. A statement by the artist emphasises the ‘pattern of slowness’ as a form of regenerative energy in the modern world. The Triennial showcased strong ideological and stylistic differences between the two Koreas. A large section of the exhibition was 13 works by eight artists from the Mansudae Art Studio in the Democratic Peoples’ Republic of Korea (North Korea), curated by the filmmaker, Nicholas Bonner. The works were all Socialist Realism with its emphasis on figurative art, realism in context, and socialist values in themes, predominantly the representation of work and workers. The strongest characteristic of socialist realism is that technical ability and craft skills provide the critical criteria rather than content or process, as for example in the process-oriented work of Kyungah Ham or Chen Quilin, or meaning in the work of Kibong Rhee. The continued adherence of the DPRK to out-dated and meaningless artistic systems does not allow their artists to express other structures of feeling so clearly evident in the work of artists included in Asia-Pacific Triennial 6. |

Dr Van den Bosch is an Adjunct Research Fellow at Monash Asia Institute. Her article 'Professional Artists in Vietnam: Intellectual Property and economic and cultural sustainability' was published in the Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society 2009, vol. 39, issue 3, pp.221–236. |

LECTURES AND EXHIBITIONS |

| Hymn to beauty: the art of Utamaro Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806) is the quintessential

exponent of ukiyo e woodblock prints of Japanese courtesans His sensuous

and insightful portraits of women from all walks of life—aloof

courtesans, diligent housewives, affectionate mothers and passionate

lovers—have enjoyed unabated popularity in Japan and worldwide.

Featuring around 80 prints from the renowned collection of the Museum

of Asian Art, State Museums in Berlin, this exhibition is the first

extensive survey of Utamaro’s work in Australia and also includes

work by his contemporaries. Further

information. |

2010 Arts of Asia Lecture Series—Powerful

Patrons, The 2010 Arts of Asia lecture series explores the pre-eminent

individuals in Asia who have shaped the arts, culture and sense of identity

of their peoples. Lectures will include well known historical identities,

such as Ottoman sultan Suleyman the Magnificent and Shah Jehan, architect

of the Taj Mahal. However, the series will also explore other influential

leaders who are less widely known, such as Korean King Cheongjo, himself

a painter, who sponsored Buddhist temples and created the royal library

or Tibet’s 5th Dalai Lama, who oversaw the efflorescence of Tibetan

artistic style and set into motion the creation of the Potala Palace.

Art Gallery of NSW Director Edmund Capon launches the series of two

terms of 12 lectures each by introducing the legacy of China’s

First Emperor Qin Shihuangdi. Full

program and online booking. |

Buddhism

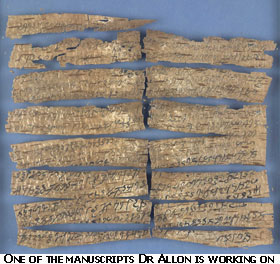

| The focus of my research of the past decade has been the new discoveries of ancient Buddhist manuscripts from eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, a region centred on what was known in antiquity as Gandhara. Lying on the major trade routes that connected India with Central Asia, China, and the Iranian and Mediterranean worlds, Gandhara was an important territory for several major empires, beginning with the Achaemenids (Persians), then the Greeks under Alexander, the Indian Mauryans, Kushans, and so on. As a consequence, a great diversity of religious, cultural, and artistic traditions were absorbed by Gandhara as seen, for example, in the artwork of the early centuries CE in which Greek, Roman, Indian, Iranian, and Central Asian features are discernible. But, undoubtedly, it was the introduction of Buddhism from lands to the east that would determine most profoundly the character of Gandhara for much of its early history. Introduced by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE, Buddhism was the dominant religion in the North-west from at least the 1st to the 7th or 8th centuries CE, continuing to flourish at some sites until as late as the 11th century CE. This long and prosperous history of Buddhism in the North-west is witnessed by a wealth of archaeological remains, innumerable art objects and inscriptions of Buddhist subject matter, and by the accounts of visitors to the region, such as the Chinese pilgrim monks who visited its famous pilgrimage sites before continuing on to India. Yet until recently only a few fragments of Buddhist texts, remnants of what must have been a huge corpus of literature, survived. Since the early 1990s, large quantities of Buddhist manuscripts have been discovered in the region and have made their way into public and private collections in Pakistan, Japan, Europe, and the United States. Dating from approximately the 1st century CE, if not earlier, to the 8th century CE these birch bark, palm leaf, and occasional vellum manuscripts contain texts written in either Sanskrit or Gandhari (a Middle Indo-Aryan language related to Sanskrit). A few Bactrian documents have also surfaced. |

The full significance of these manuscripts is still being realised. The earliest are the oldest Buddhist manuscripts yet discovered and as such they provide us with examples of genres and texts at a particularly early stage of their development, as well as revealing much about the development of collections and canons. They represent the first examples of texts of some early Buddhist schools and substantially increase the corpus of those for which we already have witnesses. They represent a substantially different form of evidence for the history of Buddhism in Gandhara to those used to date, and will have a major impact on our understanding of the development of Buddhist thought and practice both in this region and elsewhere— for example, these documents are significant for the history of Buddhism in Central Asia and China since Gandhara was the source and sometimes the conduit for the transmission of Buddhism to these lands. |

They also give us some insight into the types of texts being studied by Buddhist communities at this early period and the ideas, doctrines and practices that occupied them. Again, these documents are significant to language studies, particularly the Gandhari texts. My research as part of the Early Buddhist Manuscript Project is primarily concerned with the Gandhari language texts among these new manuscript finds which generally predate the Sanskrit material. It involves identifying the texts, reconstructing the often fragmentary manuscripts, producing editions, translations and studies of them, thereby making this material available both to a scholarly audience and to the wider interested public. Other important components of the work include determining the relationship of these texts to parallels preserved in other languages, such as Pali, Sanskrit and Chinese; producing studies of the paleography, orthography, and language of the paleography of these documents; identifying the likely reasons for their production; and, ultimately, understanding their significance. I am working on a catalogue and overview of the Senior collection of Gandhari manuscripts, which date to the second century CE. This collection consists of 24 birch bark scrolls, which were interred in a clay pot in a sacred site (stupa), and includes some 41 texts. Few scholars have the skills (or inclination) to work with this material. Although difficult, I find this research particularly rewarding. In some cases I am the first to read a text since it was written on birch bark almost 2000 years ago by a monk whose world view and experience was so radically different from our own. It contributes to the preservation of the Buddhist heritage of Afghanistan and Pakistan and improves our understanding of the fascinating history of these lands. Hopefully, this work may spark in these countries an interest in their Buddhist past. In this regard, it is unfortunate that no Afghan and few Pakistanis have the skills required to work with these documents. As only a small proportion of these texts have been

published, I will never be short of research topics to pursue. Yet

Buddhist texts in the Pali language, which were the subject of my

doctoral research, remain ever enticing. |

Dr

Allon is Chair of the Department of Indian Sub-continental

Studies and Senior lecturer in South Asian Buddhist Studies at the

University of Sydney. |

||

Student of the Month

LIFE BEHIND BARBED WIREPhD student Tang Ten Phee is researching a neglected area of the 1948–60 Malayan Emergency—everyday life behind the barbed wire of Chinese New Villages. |

When

I was a child and a young man growing up in Malaysia, my grandparents

often shared stories of how difficult life was in the Chinese New

Villages in which they lived under strict British colonial control

during the Malayan Emergency. These stories form an integral part

of my childhood memories, and I developed a deep yearning to understand

the past of the Chinese in Malaya under British rule. I finally had

the opportunity to do so through my PhD thesis. When

I was a child and a young man growing up in Malaysia, my grandparents

often shared stories of how difficult life was in the Chinese New

Villages in which they lived under strict British colonial control

during the Malayan Emergency. These stories form an integral part

of my childhood memories, and I developed a deep yearning to understand

the past of the Chinese in Malaya under British rule. I finally had

the opportunity to do so through my PhD thesis.

Over several decades, there has been much scholarly interest in the Emergency. However, most of these academic studies adopt military and security perspectives, particularly in the context of the Cold War. Others have shown an interest in the Emergency as a successful counter-insurgency strategy, focusing on new techniques in psychological warfare such as the winning-hearts-and-minds approach. Overwhelmingly, the existing literature has taken a top-down or state-oriented approach to the subject. There remains a vital gap in the historiography of the Emergency, in particular its socio-psychological impacts on relocated New Villagers. During the 12-year ’shooting war’, one of the Emergency’s most important and enduring social impacts was the relocation of nearly 500,000 rural dwellers, mainly Chinese squatters, who were viewed as dangerous allies of the Communists. Hundreds of thousands of squatters and their families were scattered into more than 480 resettlement camps, later known as New Villages, throughout the peninsular. The British authorities attempted to mask the trauma of forced removal by portraying the settlements as progressive, modern improvements. Colonial rhetoric and uncritical commentators continue to frame this period as a counter-insurgency success and negate the hardship endured by ordinary people in Malaya from the draconian measures to retain colonial power. My PhD study aims to narrow this gap by examining the Emergency through the social experiences of marginalised and dislocated New Villagers. Through a history-from-below approach that emphasises the memories and voices of the New Villagers, I reconstruct contested meanings of resettlement and life behind barbed wire. |

This examination includes how New Villagers responded to government policies as well as community interactions as part of everyday life. Between June 2007 and May 2008 I conducted my fieldwork with financial support from the School of Social Sciences and Humanities Bursary and the ST Leong Scholarship, Murdoch University. This allowed me to spend time in the archives in Malaysia and Singapore as well as visit 150 New Villages on the Malay Peninsula to create a local–regional comparative database. From this, I selected four case-study sites and conducted 76 oral history interviews in local dialects. These testimonies, gathered from respondents aged 70 years and over, shed new light on a period of untold suffering and highlight the desperation as well as resilience of those who lived through such turbulent times. At the last stage of my fieldwork—with the support of the Kuala Lumpur and Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall—I co-organised a history exhibition and forum on New Villages and the Emergency, in Kuala Lumpur, in April 2008. I believe history should be accessible to ordinary people and welcome opportunities for greater interaction between members of the public and historians/researchers. Most recently, I was awarded the 2009 Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship by the National Library Singapore. As part of the fellowship, I am researching the assassination of the British High Commissioner to Malaya, Henry Gurney, in 1951 and the case of Tras New Village. Since January I have been focusing on the unique case of Tras New Village, in the state of Pahang, and its links to the assassination. This micro-level study, which will conclude in July, aims to analyse how the assassination implicated and changed the New Villagers’ lives in Tras during the Emergency. In the near post-PhD future, I plan to set up a website on New Villages as a medium to connect the past to the present. The site will allow me to share an online archive of valuable old photographs as well as interact with the public. I intend to continue my academic journey by applying for post-doctoral research projects exploring the themes of forced resettlement and state intrusion upon ordinary lives within a comparative framework. In time, I hope to return to Malaysia and contribute what I have learnt over the years. |

| Tan Teng Phee is a PhD candidate at the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, Western Australia. He grew up in Malaysia but obtained his BA and MA in Taiwan. After working for five years as a research assistant and part-time lecturer in Tunghai University, he received an Endeavour International Postgraduate Research Scholarship and commenced his PhD program in 2006. | |

Books on Asia

| The days of Australia being a relatively homogeneous society are long gone. The social mix in our communities, most especially our urban communities, is increasingly diverse and becoming more representative of Asian than European cultures (the proportion of Australians from Asian backgrounds is 10 per cent and rising according to recent statistics). Yet the literature available for our children and young adults is hardly reflective of this growing diversity and still more inclined to being Eurocentric or at least more Western in its approach. In addition, although we recognise the growing importance of our Asian neighbours as trading partners, and despite the fact that Asia is becoming an increasingly popular holiday destination, finding anything beyond a tour guide in a local bookshop is generally somewhat difficult. However, there are some excellent books available, not only about the Asian ‘giants’ of China, Japan and India, but also about smaller countries in Southeast Asia, and these range from the simplest picture books to bilingual books, to books about the history, culture, and traditions of our nearest neighbours. Folktales seem to be a staple of picture books about other countries and can be an excellent introduction to other cultures for young children. They combine a sense of adventure with details particular to that country and many have been retold and given a more contemporary treatment often with stunning illustrations.

Adeline Yen Mah, whose best-selling memoir Falling Leaves has also been abridged into a young person’s edition called Chinese Cinderella, has come out with an informative introduction to the history of China, China, Land of Dragons and Emperors—less a textbook than a diverting encounter with aspects of Chinese culture through the ages. With information being so easily accessible, it is easy to understand the appeal of books that give links to updated websites, and one publisher has managed to do this with the Usborne Internet-linked Introduction to Asia. |

It gives links to sites containing maps, activities, information, and art projects and saves the student or parent having to sift their way through hundreds of irrelevant links. Besides information books for the older child there is a growing number of novels written with Asian protagonists or themes and this is quite often a result of a particular author’s heritage, area of interest or just having travelled to Asia. Among Australian writers, Gabrielle Wang is a fourth-generation Chinese who has written half a dozen novels with a strong Chinese background for the younger reader, and her first young adult novel, Little Paradise—to be published in March—is based on her mother’s life.

Author/illustrator Sally Heinrich has also made Asia more accessible because of her own engagement with various countries in Asia. She has lived in Singapore, where she had a series of books on multicultural festivals published, and was the recipient of an Asialink literary residency grant. Her gorgeously illustrated The Most Beautiful Lantern reflects the vibrant colours and excitement of the Lantern Festival that is a feature of Chinese communities all across Asia.

Boys need no encouragement to read when books are exciting survival stories such as these, or based on martial arts such as The Samurai Kids series by Sandy Fussell. Well-researched and fast moving, these feature a group of children whose differing challenges are no barrier to their being able to achieve success through teamwork and are set in ancient Japan. Japan’s feudal era is also the setting for Simon Higgins’ Tomodachi, a gripping boys-own adventure. Lian Hearn has also used Japan as the setting for her young adult Tales of the Otori sequence, albeit in a deliberately vague period of time. It is a lyrically written evocation of the culture and traditions of medieval Japan as experienced through the main characters. As Hearn herself says, it is important to write about other cultures simply because it ‘helps to understand other nationalities if we try to make an imaginative leap into their world’ while being careful not to make assumptions and to guard against our own cultural standpoint by using ’great humility and respect—and a lot of hard work’. The number and the quality of writers and illustrators writing about Asia and Asians can only develop our children’s understanding, and the sooner parents and teachers can include these books in their literary diet, the better they will be for it. If we are to ensure that the vision enunciated by Julia Gillard that ‘by the time Australian students leave school they should have a sound knowledge of Asia—its geography, history, peoples, cultures, and languages’ comes about, it is imperative that we introduce them to such books without delay. |

Lynette Thomas

joined Asia Bookroom in

2008 after 10 years with Bookaburra, a specialist children's bookseller

in Singapore which she co-owned and managed with a fellow Australian.

She has two children, now in their 20’s. |

|

MEMORY IS ANOTHER COUNTRYNathalie Huynh Chau Nguyen explains why she chose the topic of memory for her latest book on Vietnamese women. |

|

Growing up in Australia, I often looked to the past because it seemed to be a much happier place. Everything changed for my family when we lost our country in 1975. We became stateless and arrived in Australia as political refugees. We had to reconstruct our lives in a new country. This fascination with the past is the reason why I am interested in memory, and in particular the memory of refugees. In my work I explore how and why people remember the past, and why they need to remember the past in a particular way. For refugees, memory acquires a particular power and poignancy, since the country that they remember is now lost to them. Like the histories of the post-Holocaust generations, Vietnamese diasporic histories are often fragmented and incomplete. Members of the first generation invested their energies in adjusting to dislocation and migration, and with reconstructing lives and identities in a different country and culture. Many did this while mourning the loss of their homeland and of family members who had either died or disappeared in the post-war years. I wanted to tell the stories of Vietnamese women because their stories are still largely unknown and undocumented. It has now been more than 30 years since the end of the Vietnam War, and more than 30 years since the first Vietnamese refugees arrived in Australia after the fall of Saigon and the collapse of South Vietnam in 1975. A generation after the end of the war, I think the time is now right for Vietnamese refugees and migrants to reflect on their former lives in Vietnam as well as their new lives in this country. My book is based on the oral histories of 42 Vietnamese women. Women speak of their experience of war, dislocation, and migration. They remember their homeland and those they have lost. Their stories are framed by trauma and loss but they also reveal a fascinating glimpse of life in South Vietnam before 1975, the changes that occurred in post-war Vietnam, and women’s fortitude in rebuilding their lives in the aftermath of war and displacement. One of the great challenges of oral history is the time and effort involved in creating an archive of primary material. When there is more than one language involved, as is the case here, and many of the stories are trauma narratives, this work is even more delicate and difficult. |

Women are also hesitant to bring their private stories into the public domain. Once women have made up their minds to speak however, they do so with astonishing honesty. I am constantly surprised about this and about the fact that they are prepared to entrust painful and difficult events in their lives to the interviewer. A number of women reflected on how hard it was to tell their stories to their children. They conveyed to me how glad they were that I was writing a book on Vietnamese women’s experiences, and expressed the hope that their children would one day read and understand their stories. In this light my work serves as a bridge between the different generations. This difficulty of conveying stories, especially stories of trauma and loss, is recognised by the second generation of Vietnamese Australians. One of the women interviewed for the book, Thy, was one year old when her family escaped from Vietnam by boat in 1979. She has no memory of either Vietnam or the exodus but bears the imprint of the previous generation’s trauma. For Thy, Vietnam is an imaginary place shaped by the stories of others and by old pictures, news footage and documentaries of the Vietnam War. Her recollection interweaves her parents’ experience of war, trauma, and dislocation, with their imperfect transmission of this experience to their children, and her own frustrated efforts to obtain more information. She says:

Thy’s story is uniquely hers but one that also will undoubtedly resonate for many second-generation Vietnamese Australians. |

Nathalie

Huynh Chau Nguyen is an ARC Australian Research Fellow at the

Australian Centre, School of Historical Studies, University of Melbourne.

Her second book, Voyage of Hope: Vietnamese Australian Women’s

Narratives, was shortlisted for the 2007 NSW Premier’s Literary

Award. Her latest book, Memory

Is Another Country: Women of the Vietnamese Diaspora, was released

by Praeger in 2009. |

|

VIDEOCHRONIC: VIDEO ACTIVISM AND VIDEO DISTRIBUTION IN INDONESIA |

Colour illustrations, including a visualisation of the development of video activism and online video, 140pp, November 2009. ISBN 9780646520001. $10.00 + postage. The result of a collaborative research project charting how activists are engaging with video technologies in Indonesia, this publication addresses some of the issues of technology-mediated social movements and explores the potential and limitations of online video distribution. Since the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime, a host of new media projects has emerged. Individuals and organisations dealing with issues such as the environment, human rights, queer and gender issues, cultural pluralism, militarism, poverty, labour rights and globalisation have embraced video as a tool to communicate with both their bases and new audiences. Order a copy or download pdfs. |

|

NEW BOOKS FROM THE ASAA SERIES Special Price (20% discount) for ASAA members Books can be ordered through Asia

Bookroom KITLV Press is developing new subseries within the Verhandelingen Series. The editorial board has recently approved two new subseries: Power and place in Southeast Asia, edited by Ed Aspinall and Gerry van Klinken. More information. Southeast

Asia mediated, on media old and new, mass, alternative, and grassroots,

both today and in the past, edited by Bart Barendregt and Ariel Heryanto.

More information. |

Awards and grants

| INDONESIAN ADDED TO FULBRIGHT LIST Fulbright has added Indonesian to the list of eligible languages for Critical Language Enhancement Award funding. Students interested in proposing study or research in Indonesia, including music, dance and theatre, have an excellent chance of receiving extra funding. Go to the Fulbright website (in both the Critical Language Enhancement Award Program information and the individual Participating Country Summary for Indonesia) for more information. AWARDS AND GRANTS FOR THE STUDY OF JAPAN PM ANNOUNCES FIRST AUSTRALIA ASIA ENDEAVOUR

AWARDS The Award provides 20 postgraduate students and 20 undergraduates from across Australia with up to $63,500 to undertake an international research, study and internship experience in either China, India, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Republic of Korea, Taiwan, Thailand or Vietnam. Ten international postgraduate students will also be funded to study in Australia. The Government has committed $14.9 million over four years to establish the program, which was announced as part of its response to the 2020 Summit. From next year, the awards will form part of the Australia Awards initiative, announced by the Prime Minister in Singapore on the 13 November 2009. The Australia Awards will better co-ordinate and promote the more than $200 million of existing Australian scholarships. A further $18 million will be spent on the Australia Asia Awards for individuals who have already demonstrated their potential to be leaders within their own countries, and for students from developing Asian countries. Further information, including the list of the 2009 Award holders. NLA JAPAN FELLOWSHIP |

Positions vacant

|

JOB WEBSITES These sites offer career prospects for graduates and postgraduate in Asian Studies. If you know of other useful sites advertising jobs for postgrads in Asian Studies, please send them to allan.sharp@homemail.com.au. http://www.jobs.ac.uk and http://www.acu.ac.uk/adverts/jobs/ advertise worldwide academic posts. http://isanet.ccit.arizona.edu/employment.html is a free-to-access website run by The International Studies Association. http://www.reliefweb.int is a free service run by the United Nations to recruit for NGO jobs. http://www.aboutus.org/DevelopmentEx.com has a paid subscription service providing access to jobs worldwide in the international development industry. http://h-net.org/jobs is a US-based site with a worldwide scope. Asia-related jobs (mostly academic) come up most weeks. http://www.aasianst.org/ is the website of the Association for Asian Studies. New job listings are posted on the first and third Monday of each month. You must be a current AAS member to view job listings. http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/. The Times Higher Education Supplement. http://www.comminit.com/ is the site of The Communication Initiative Network. The site includes listings of jobs, consultants, requests for proposals, events, trainings, and books, journals, and videos for sale related to all development issues and strategies. You can view all posts on these pages without registering, but will need to register to post your items. |

Diary dates