In the News

| Climate change poses serious threats to India and will adversely affect agriculture, water resources, coastal ecosystems, forests, biodiversity and human health. It also poses the threat of large-scale human displacement from low-lying coastal areas. However, India still resists measures that would result in a binding agreement on emissions reduction, steadfastly holding to a position that developed western countries are mainly responsible for emissions and global warming and should therefore bear the responsibility of mitigation. So far, India has been maintaining this stand for the forthcoming Copenhagen conference. There are two main reasons for India’s reluctance to be bound by any agreement on an emissions cap. First, economic development is the foremost priority that drives all policy considerations. Second, India is arguing for equitable measures and emphasises the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ for various nations to tackle climate change on a global scale. Since India gained independence in 1947, its policy thrust has been economic development. India’s Planning Commission, the apex body responsible for the country’s planned economic development, made it clear in 1952 that the main objective of planning was to raise living standards. The planned state intervention has resulted in a robust industrial infrastructure. However, for decades India’s economic growth was disparagingly low. In the early ‘90s, India adopted open-market policies coupled with deregulation and the promotion of private and foreign investment in various sectors of the economy. Since then, economic growth has been steady, between 6 and 9 per cent. Still, a large section of over one billion people lives below the ‘poverty line’. It is envisaged that to meet the development goals and to eradicate poverty the country would require a sustained annual economic growth of 8 to 10 per cent for the next two decades. The emphasis on economic growth, however, has environmental implications. India’s environment is in disarray, as manifested, among other things, by deforestation, desertification, soil degradation, water and air pollution, growth of urban slums, and unhygienic living conditions. Environmental issues have long been a low priority for Indian policymakers. At the 1972 UN Conference on Human Environment at Stockholm, the then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi made the point that poverty is the worst polluter, indicating India’s priority for economic development and poverty alleviation. This, however, does not mean that no policy decisions have been taken on environmental issues. A number of laws have been enacted such as The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1974, Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act 1986, and the Environment Protection Act 1986. A Department of Environment was set up in 1980, followed by the Ministry of Environment and Forest in 1985. Within the global climate-change regime, India also has been an active partner in multilateral negotiations on climate change. It treats the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 1992 as a legally binding multilateral instrument to deal with the challenges of climate change. The principle of ‘differentiated responsibilities’ is of specific interest for Indian policymakers. After initial hesitation, India ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 2002. |

In a recent statement about the Copenhagen summit, the Indian government emphasised the validity of the UNFCCC, which will continue to guide India’s future activities and responses on climate change. Apart from insisting that there should be no emissions cap for developing nations, India has also highlighted the necessity of unconditional support from the developed nations on transferring green technologies and funds to ensure sustainable development. India’s insistence on ‘differentiated responsibilities’ has three underlying reasons. First, from the ‘stock’ perspective, India argues that the accumulation of greenhouse gases (GHGs) is a result of the industrialisation process in the developed nations. As the data reveals, India’s contribution to cumulative carbon dioxide emissions between 1850 and 2000 has been 2 per cent compared to a combined 57 per cent for the United States and the European Union. India, therefore, calls on the developed nations to fulfil their ‘historical responsibility’ of mitigating emissions. Second, from the ‘flow’ perspective,

though India is ranked fifth in the category of major polluters, contributing

to As the GRID-Arendal (a collaborating centre of the United Nations Environmental Program) figures show, in 2002 the per capita carbon dioxide emissions for India were 1.1 tonnes, compared to 20 tonnes for the United States. In Australia, per capita carbon dioxide emissions were 18 tonnes. Third, India sees that the lack of commitment from the developed nations for unconditional support on transfer of green technologies and funds will result in dependency relationships. India therefore sees its position as based on a principle of ‘global equity’. It has received strong support from the civil society organisations working in areas of environmental and climate change. The case of the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a Delhi-based NGO and research think tank, is important. In the 1980s, CSE published two citizens’ reports, both scathing of the perilous state of India’s environment. However, CSE came out strongly against the propositions of a World Resources Institute (WRI) report questioning the veracity and validity of the data. In 1990 the WRI, in collaboration with the United

Nations, published a report on the state of greenhouse gas emissions.

|

The report suggested that developing-countries’ emission contributions were almost equal to those of the developed nations, including the then USSR and Eastern Europe, indicating that developing countries, such as India, should share the blame for global warming. In calculating country-wise emissions, the report heavily emphasised emission production on the basis of deforestation, rice fields and livestock, while underplaying the emissions produced from burning fossil fuels. Pointing to the WRI report’s prejudiced way of data calculation and projection, the CSE termed the exercise an example of ‘environmental colonialism’. The CSE came out with its own comparative data indicating that industrialised nations contributed almost two-thirds of greenhouse gas emissions. Later studies vindicated the CSE stand, showing that developed nations contributed almost 70 per cent of GHG emissions. Indian policymakers have used the CSE data to support their demands for an equitable response to the challenges of climate change. However, threats of climate change are real and, in India’s case, pressing. Prolonged neglect will threaten the life and livelihood of millions of people. India is also coming under consistent pressure from the western nations, especially the United States, which is insisting that emissions need to be measured by volume rather than on a per-capita basis. Moreover, India’s armour of ‘equity’ is developing chinks. A recent Greenpeace report titled ‘Is India Hiding Behind the Poor’ has raised the issue of internal climate injustice, where a relatively small wealthy class produces high emissions that are ultimately balanced by millions of poor people to keep it at a low per capita rate. India’s energy-consumption patterns are an example. Two-thirds of India’s population live in rural areas and 80 per cent of them are reliant on biomass energy to meet their daily requirements. In last few years India has taken some positive measures. In 2004 it finally fulfilled its commitment to the UNFCCC by bringing out the Initial National Communication, a report consisting of scientific information on issues, such as GHG emission, inventory estimations and climate vulnerability. In 2008, India also unveiled the National Action Plan on Climate Change. Though silent on the issue of mitigation, the Action Plan emphasises the need to achieve India’s development goals in a sustainable manner. The Indian government has subsequently announced a $20 billion solar-energy program and a $2.5 billion forestation fund. The Integrated Energy Policy 2006 is another effort to meet the sustainability criteria by emphasising diversification of fuel choices and supply sources. Moreover, the energy intensity of India's GDP has fallen from 0.30 kilogram of oil equivalent (kgoe) per dollar of GDP in 1980 to 0.16 kgoe in 2004. India’s stand at the forthcoming Copenhagen meeting will be based on the fact that it has taken some measures, while the developed countries so far have failed to meet their emission-cut obligations. This puts India in a comfortable situation to bargain, despite pressure, particularly from the United States, to join the agreement on emissions reduction. However, the situation is not an ‘enjoyable’

one, as the country's environment minister Jairam Ramesh has claimed,

because dealing with climate change is a pressing necessity rather

than a luxury for India. |

| Dr Tulsi Charan Bisht recently finished his PhD in Anthropology from La Trobe University. |

||

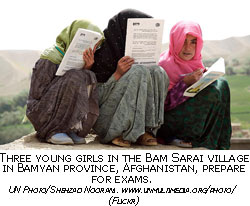

Focus of Afghanistan

| It's not evident that any of President

Obama's advisors, such as Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Vice-President

Joe Biden, Secretary of Defense Robert Gates and the Joint Chiefs of

Staff, are giving any weight to the cause of women as a relevant factor

in determining future strategy in Afghanistan. When it comes to women, the war has been another disaster, and has obscured the continuing denial of their civil and political rights, and its deleterious impact. |

Their hopes raised during the early days of the invasion have turned into a poignant despair. With the warlords and the Taliban controlling about 90 per cent of Afghanistan, it's not surprising to hear, as one notable Afghan women activist put it, that the invasion has led to ’no positive change’ regarding the situation of women. This is a horrendous result for women, when combined

with the failure of the war to achieve its other two stated goals. Al

Qaeda in Afghanistan, according to General James Jones, national security

advisor to President Obama, has been reduced to 100 people, although

al Qaeda members in Pakistan and other parts of the world seem to have

proliferated. This is apparent from the amount of terrorist attacks

around the world. From London to Mumbai, from Madrid to Islamabad, and

from Baghdad to Jakarta, terrorists have unleashed unspeakable horror

and destruction, sometimes with impunity. |

That is where the focus should be, not on adding more troops to wage war. Moreover, securing the rights of women is probably the best way to aid Afghanistan's indigenous democracy. To be sure, the Taliban in the past has been fervently against women's rights but could the United Nations broker an agreement whereby the war would be ended in exchange for a guarantee by the Taliban and the Karzai government to respect and promote women's rights? If so, such an agreement, in addition to guarantees by the warring parties to prohibit al Qaeda and its offshoots from maintaining a sanctuary or training ground in Afghanistan, would be a promising start for concluding the war. What exactly would this entail? First, the international community, through the United Nations, should adopt a policy akin to a zero tolerance approach to the pursuit of gender equality and the eradication of violence against women, a gender fundamentalism if you will. This means that women’s equality, along with the campaign to provide democracy, would be the raison d’etre for international engagement. This must be the commitment of the international community. The role and status of women would become an important measure of the achievement of democracy in Afghanistan, perhaps a harbinger of democracy. In attempting to work out such a settlement with the Karzai government and the Taliban, the international community should look to other successful international campaigns, such as the anti-apartheid campaign, as a model on which to base a political and diplomatic approach regarding Afghanistan. Through a concerted global campaign, the international community succeeded, along with internal pressures, in persuading the ruling white government in South Africa that the continued denial of basic political rights to black South Africans was self-defeating and ultimately destructive. Similarly, through a combination of diplomatic carrots and sticks, the international community through the United Nations should engage in a concerted attempt to get the competing forces in Afghanistan to commit themselves to pursuing women’s rights to equality. This should be more than a series of moral exhortations, but should involve committed and strategic interventions by the United Nations. After all, what sense does it make to conduct a war without willingness to conduct peace talks? |

Professor

Andrews is an International expert on human rights and

Chair in Law at La Trobe University. |

||

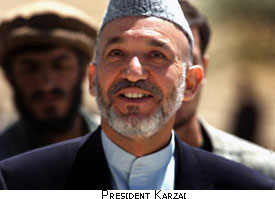

| Soon after the incumbent Karzai was declared president of Afghanistan again in early November, US president Barak Obama telephoned him to congratulate him on his re-election and to tell him that his administration needed to be more serious in its efforts to eradicate corruption. Obama reported that Karzai had assured him that he understood the importance of doing so, but ‘as I indicated to him’, said Obama, ‘the proof is not going to be in words; it is going to be in deeds.’ Obama’s statement has set the tone for Afghanistan’s key allies in their relationship with the new government for the next five years. The new government is now in a much weaker position because Karzai’s re-election was undermined by voting irregularities and the cancellation of the second-round run-off after Karzai’s main challenger, Dr. Abdullah, withdrew when his demands for changes in the electoral commission were not met. Pressure on Karzai from the international community to fight corruption and establish a credible government has placed him in a position to make tough decisions. This, of course, will be politically costly to him if he fails to fulfill commitments made to his local allies in return for their support during the campaign. The challenges facing the new government could undermine the war against terror—rebranded the ‘Overseas Contingency Operation’ by the Obama Administration—and also challenge the perception of state legitimacy. The most critical challenge, however, is corruption and drugs, which fuel the Taliban insurgency and widen the gap between the government and the people. If Karzai fails to take urgent measures and the government does not deliver results, it will further worsen the security situatin and misuse of power. |

As far as financial management is concerned, the international community has more of a role than the government. The way aid is channeled to Afghanistan, and the ineffective use of this aid, fuels corruption. More than 70 per cent of aid money bypasses the state and goes directly to mainly international implementing agencies. In most cases, these agencies sub-contract aid delivery to local companies, which then charge 10–15 per cent administrative costs for each project. Security remains an indicator of success. The lack of consensus on the war against terror and counter-insurgency approaches has helped the discredited Taliban regain military strength and new political influence. The United States’ new strategy, with its focus on increasing troops and protecting the population might improve things, but not sufficiently without an effective ’Afghanistan Strategy’. Afghan security needs to get strengthened, and any domestic and international increase in troops will need to be done in a historically informed and culturally sensitive way. Mostly, Afghanistan’s security will remain dependent on the success of the war against terror in Pakistan. |

Because of the political strife and insecurity, development and investment in Afghanistan have been neglected, and where they do exist they are poorly supported and delivered in many sectors. This demands competent and committed Cabinet leadership, including at the technical level, to deliver results. Karzai is soon to announce his new cabinet and commitments for the next five years. Despite the political instability of the presidential election, there is now an opportunity to foster reforms in government structure and leadership, and to address constitutional shortcomings. However, history indicates that until the Afghan people participate in the political process and there is mutual accountability, or a ‘double compact’, between the international community and the Afghan government, and between the government and the public, it will be difficult to expect much improvement in the medium to long term. The government’s commitments for the next five years, the composition of the new cabinet, and evidence of some quick reforms will lay the grounds for the Afghan people to judge and trust the new government. Insurgency activity may decrease during the coming winter, but this will depend on how quickly Afghan and NATO security forces organise themselves to maintain, at least, a minimally secure environment. The government’s top priority remains the restoration of public trust and building the confidence of its western allies, which will be conditional on some immediate measures to improve governance. The next six to 12 months will show whether Afghanistan is going in the right direction or facing a new period of crisis. |

Nematullah

Bizhan is PhD scholar at the Australian National University and

former head of the Afghanistan National Development Strategy Policy,

Monitoring and Evaluation Unit. His previous report on the Afghan presidential

election appeared in the September issue of Asian Currents. |

||

Cities and Society

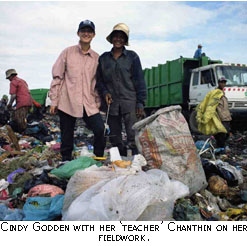

| The touristic trend where people visit sites of death or suffering has been termed ‘dark tourism’1. Within Asia, Phnom Penh offers opportunities to satisfy this rather macabre desire. As part of a busy itinerary, many tourists visit the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and then often travel 20 minutes out of town to the memorial site and mass graves, known as the Killing Fields. If that’s not enough, half-way back to the city, tourists can stop at the city dump in Stung Meanchay to experience people suffering now; families scraping a living by picking for recyclables amongst the city’s waste. However, they need not visit the dump to see it, as images of waste pickers frequently flash across news screens to encapsulate all the woes of the developing world. A New York Times article described the dump as one of the saddest sights in the city, and quoted an aid worker as saying, ’this is the closest thing to hell on earth I've ever seen’. Even US Senator John McCain’s wife visited the Stung Meanchay dump. An NGO worker said, ’she even hugged some of them, regardless of their dirty clothes’. Visitors to Stung Meanchay dump often describe it as a traumatic experience. After climbing one of the three mountains of waste—a collection of over 40 years of detritus—tourists find, on average, 250 people picking through garbage. Because the miasma enters the nose, sending messages to the area of the brain that governs emotional responses, it is hardly surprising the experience is upsetting. This leads me to wonder: could the dump be what Julia Kristeva describes as a space of abjection? In turn, the sights and smells often trigger a feeling of wanting to help. Many groups of tourists give out money to the waste pickers during their visit or return to the dump with gifts of food, clothing and medicine. Some vow to support the many aid organisations that have been set-up, mostly by foreigners, to provide alternative income, food, rice, clothing and schooling for children. The waste pickers have come to symbolise poverty in Phnom Penh. Although they are often labelled as impoverished, they are not exactly the poorest residents of the city. The waste pickers collect recycling out of necessity, but their daily income is above the $1.35 per day World Bank yardstick of poverty in Asia, and often they can earn almost double that of workers in garment factories or construction. They also have the added advantage of being able to collect objects from the dump to use in their homes, and occasionally they experience windfalls when they find mobile phones, jewellery or cash. |

The waste pickers live side by side in slum settlements on private land surrounding the Stung Meanchay dump. Most are average Khmers; former farmers who have migrated to the city specifically to work at the dump. Nor do they come from the lower rung of a caste system or an oppressed ethnic minority. The decision to become a waste picker is not necessarily a last resort, but often one of choice (albeit among only a few options) to secure more financial independence. As one of my informants tells me, ’I will never forget the grace of the dumpsite,’ so glad that she had the opportunity to start a life as a waste picker. Within their community, waste pickers represent themselves as being proudly hard-working, often sharing found food with neighbours, or parading their discoveries to their friends; ’Where did you get those new shoes?’ a neighbour asks. ’Phsar Lerr’ (from the market on top of the mountain) is the playful response. They understand the immediate risks involved, as injuries and illnesses are common and people have died from accidents, but despite the risks they do the work because of the benefits it offers their families. In their community, they celebrate their industriousness and thrive on the adventure of the work. Outside their community, however, they are aware that they are re-cast as something much different—as being dangerous, contaminating and not to be trusted. Many recount stories with anger when outsiders have called them pigs or animals. I often wondered how the waste pickers felt when tourists and visitors came to the dumpsite to stare at them and take photos. Is it a form of voyeurism, and do they feel upset by it? ‘If they come and give us some money or food, then it’s ok, |

they feel pity for us, but if they come and don’t give us anything, then it means that they look down on us, as if we are animals, so we don’t like it when they don’t give us anything.’

In this space of abjection, where meanings shift, the waste pickers believe that visitors are evaluating them—a kind of re-valuing—as either worthy or unworthy, object/animal or human. Locally, they are verbally abused, but in the interface of the global (East meets West, rich meets poor), the act of receiving comes to symbolise their humanity. I came to learn how the community collectively exaggerated their vulnerability or impoverished status, often to their financial advantage. In turn, waste, or the politics of waste, not only enabled them to get free stuff (and lots of it) but also to feel valued. Sadly, this act has come to an end (at the time of writing this article). The Stung Meanchay dump closed mid-2009 and the municipal government opened a new ‘waste-management facility’ close to the Killing Fields. Travelling the additional 10km every day from their home, many of the waste pickers have continued to earn their daily income at the new facility, even though working conditions there have become more difficult and dangerous. Dark tourism operators, however, need not reprint their maps, as the municipal government now does not allow visitors, tourists or even aid organisations inside to see the waste pickers at work. In fact, the municipal government has stopped recycling buyers from entering the site too, with the exception of one trading company. This exclusive buyer has dramatically reduced the price of the recycling materials, resulting in an overnight cheapening of the waste pickers’ labour, jeopardising the livelihoods of the city’s most infamous workers. |

Cindy

Godden is a documentary photographer and social researcher

and is doing her PhD at the Research School of Humanities, Australian

National University. She is completing a visual-ethnography of urban

villagers who collect recyclable materials in Phnom Penh.

References

|

||

NEW FOCUS NEEDED ON ASIAN CITY GROWTHA new book argues that there needs to be more focus on mega-urban regions in Pacific Asia. Co-author Gavin Jones talks about the study. |

| What are the main themes of your new book with Professor Michael Douglass (Director, Globalisation Research Center, University of Hawaii) on Mega-Urban Regions in Pacific-Asia? We argue that there needs to be more focus on mega-urban regions (MURs), defined as the extended areas focused on the large metropolitan cities. Metropolitan boundaries for cities such as Manila and Jakarta have been widened at different times to take account of the geographic expansion of their populations, but even so, at this point most of the action in population and employment growth of these two vast cities is taking place outside the DKI Jakarta and Metro Manila boundaries. We argue that planning needs to focus on the wider mega-urban region, and this requires that data be prepared for such regions and made available in a way that facilitates such analysis. Our study examined the growth of six MURs in Pacific Asia—Jakarta, Bangkok, Manila, Ho Chi Minh City, Taipei and Shanghai—working with collaborators in each city. We used an agreed approach to defining the core, inner zone and outer zone of these MURs, and utilised unpublished census and other data to examine changes within and between these zones. How does the approach taken in your book differ from that of the UN Habitat report State of the World's Cities 2008/2009 or the World Bank’s World Development Report 2009?. |

The UN Habitat report includes small cities, and also confines its study to ‘city proper’ statistics, rather than those for urban agglomerations or metropolitan areas. Since so much of urban growth takes place outside city boundaries, it is not surprising that this study finds 40 per cent of cities in the developed world experienced negative population growth in the 1990s, and that even in the developing world, where overall levels of urbanisation rose rapidly, 10 per cent of cities nevertheless experienced net population loss. The latest World Bank World Development Report argues that spatial concentration of economic activity rises with development, and that governments should not resist it by seeking to target investment and policy attention to the lagging areas of their countries. Instead, they should adopt a neutral stance on the location of development activities, but make judicious investments in transport and communications, which will enable disadvantaged areas to become connected to the centres of growth. Despite the enormous planning difficulties posed by massive urban agglomerations, we would basically concur with this view. Did the world become 50 per cent urban in 2008? Perhaps it did, perhaps it didn’t. The point is that the definition of ‘urban’ varies widely by country. The claim that the world became 50 per cent urban in 2008 is based on accepting the national definitions of urban, which vary enormously. If all countries had used as restrictive a definition, as Thailand does, then definitely the world was not yet 50 per cent urban in 2008. But if they had used as liberal a definition as the Philippines does, then the world could be considered |

to have been 50 per cent urban well before 2008. The key point is that the world is certainly becoming increasingly urbanised, however we choose to define that term. Does research focus too much on mega cities? In some ways, yes. There has been a neglect of the dynamics of change in smaller cities and towns, where the majority of the world’s urban population lives. In other ways, no. The studies of mega cities have failed to take account of the dynamics of change in the broader MUR, as noted above, and more studies of this kind are needed. Also, the MURs have considerably larger populations than the megacities that constitute their core, and contain a disproportionate share of their nation’s top talent and productive capacity. What is the significance of cities like Shanghai, and soon Taipei and Bangkok, in being unable to sustain population through natural increase? They will have to rely on migration to maintain their population. For Shanghai and Bangkok, there is no shortage of potential migrants. But the characteristics of the migrants and their settlement and employment patterns will be a crucial determinant of the continued dynamism of these city regions. In the case of Singapore, which will also soon be unable to maintain its population through natural increase, there is a crucial difference in that all the migration to make up the difference will have to be in the form of international migration. International migrants are also playing a big role in Taipei’s growth. What are the problems of measuring migration through the conventional measure of the census? How is this a problem for understanding cities? Censuses have difficulty in enumerating all migrants

to large cities. If particular categories of migrants tend to be missed,

as they probably are, then the census data gives a somewhat misleading

picture of migration patterns. For example, if construction labourers

tend to be missed, but migrants going into middle level management are

fully enumerated, the educational composition of migrants will be distorted. |

Professor Jones has followed an academic career closely linked with consultancy assignments in the areas of population and development, educational planning and urban planning. After completing his PhD degree at the Australian National University in 1966, he joined the Population Council, where he worked first in New York, then in Thailand and Indonesia, before returning to Australia. He was with the Demography and Sociology Program at ANU for 28 years, serving as head of program for eight years, and currently holds a joint appointment in the Asia Research Institute and the Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore. |

||

Profiles

MARCHING TO A DIFFERENT DRUMMERIn the intellectual and political debates over Indonesia, Richard Robison has been a distinguished voice over four decades. He was recently elected a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. Here he talks about his work and contribution to the debates. |

|

My interest in politics and political economy emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s. This was a time of deep political divisions in Australia focused around the Vietnam War and the role of the United States more generally in world affairs. I was fascinated by the way extreme conservative ideas and interests dominated the politics of the United States and also became deeply interested in the theoretical debates of the time where dependency theory had mounted such a passionate challenge to more orthodox ideas. While I was at Sydney I became interested in the case of Indonesia. At the time, intellectual and political debates about Indonesia were virtual surrogate battlegrounds for left and right over larger questions of authoritarianism, revolution, imperialism and Australia’s place in the conflicts shaping an emerging global order. What has been your particular contribution to the debate about Asia and the process of political and social change in the region? The debate over political and social change, and specifically the case of Indonesia, was dominated in the 1970s and 1980s by two schools. Economists at The Australian National University saw the Soeharto regime as a new era of rational and technocratic rule set above the irrationalities of politics. The critics of this approach were concentrated in the politics department at Monash and heavily influenced by dependency theory and various populist ideas about peoples’ politics. They saw the Soeharto regime as a highly repressive and exploitive system operating in league with Western powers. I was profoundly unhappy with the first approach and increasingly uncomfortable with the second. My own ideas were increasingly focused on ideas about the social and economic underpinnings of state power and the influence of market capitalism on this process. I drew on a range of earlier works, including by Wertheim and some of the ideas of dependency theorists, such as Mortimer and Levine, but more generally upon theoretical works by people like Barrington Moore and the Weber/Marx debates coming out of England at the time. Indonesia: The Rise of Capital, published in 1986, was the result of this. My appointment to Murdoch University in 1977 provided the opportunities to develop a more institutionalised base for this type of political economy. In a new university, new ideas were able to flourish, and a young staff in the social sciences and humanities built their own teaching and research programs. This in turn attracted outstanding PhD students, several of whom now became important figures in the Murdoch ‘political economy school’. However, the award of an ARC Special Research Centre in 1991 enabled us to fund our own research projects and to build international networks that endure to this day. Your more recent work has examined the evolution of neo-liberalism as the defining social revolution of our time. Can you explain this in relation to Asia? |

I see neo-liberalism as more than just laissez-faire or neo-classical economics. It is an ideology that requires nothing less than that the ideas and values of the market are embedded across the institutions of politics and society. It brings new ideas about the functional nature of authority, governance, citizenship and participation into a system of technocratic and managerial rule. It is the highly complex and ambivalent relationship between neo-liberalism and many of the regimes that rule in Asia that is so interesting. Their apparent autonomy from so-called distributional coalitions, whether they are environmentalists, welfare lobbies, labour unions, and human rights lobbies, makes them attractive to neo-liberals and useful to larger strategic and ideological priorities of many Western governments. You also have a strong interest in governance and regulation—can you talk about this work in the context of Asia? To the extent that ‘good governance’ represents simply the creation of honest and efficient government, it is difficult to criticise. But the idea of good governance is more than this. It has generally been understood by its advocates as a means of most effectively regulating and protecting market agendas within an abstracted technocratic authority able to bypass competitive politics and so-called ‘vested interests’. So, in practice, it is not a neutral concept but often integral to the specific agendas for social and political change mentioned above. Does Australia have the extent and depth of knowledge of Asia to engage effectively in the region, not only at the official level, but in business, educational exchanges, development assistance, cultural and other links? It is difficult to know whether we are better placed than the Europeans or the Americans in this, or better placed than Asians in their knowledge of Australia. My guess is that we probably are. Obviously we can do better, but there are so many competing demands and priorities in education. If not, what should we be doing about it? I have always thought it would be ideal if all Australians could speak another language. However, it is clear that this will only happen if there is some sort of compulsion. Being an English speaking country there is less of an immediate imperative to be fluent in another language. And it should be remembered that knowing one of Asia’s many languages guarantees nothing about the sophistication of any broader understanding. Perhaps more realistic is the prospect of embedding the study of Asia more widely in various social science, humanities of business degrees. Here we increasingly confront the advance of various forms of rational choice and quantitative approaches in social science and business faculties where it is often believed that different countries can be analysed through sets of presumed universal data—often derived from US cases— thus negating the need for any particular cultural or political knowledge. What are you currently working on? I have just completed writing a paper with Vedi Hadiz on the political economy of Islamic politics. I am involved in an Australian Development Research Award research program on the problems of translating knowledge of politics into policy agendas in international development. Other than that, I’m trying to achieve a soft landing back in the real world after almost four decades in academia and building my interests outside those of political economy. |

Richard Robison is Emeritus Professor at the Asia Research Centre and School of Politics and International Studies, Murdoch University. He is a former Director of the Australian Research Council’s Special Centre for Research on Political and Economic Change in Asia and Professor of Political Economy at the Institute of Social Studies in the Hague. He has published extensively on the politics of markets and the way markets are being fused within authoritarian and populist forms of state authority. |

|

|

HISTORY IN UNIFORMA trip through Indonesia as a second-year university student began Kate McGregor’s passion for the country and her deep interest in its military. |

|

Through my studies of Indonesian history and other history-related topics I became very interested in official history in Indonesia. When I commenced a PhD on the topic of official representations of the Indonesian past I constantly encountered the name of one military man and the Armed Forces History Centre. So my interest in history led to an interest in the military. My thesis examined the broader efforts of the Indonesian military to produce official history in museums, monuments, films and school history textbooks. In doing this research I learnt a lot more about the military’s self-image and how this revolves around key constructions of history. Representations of the independence struggle—the most revered period of Indonesian history, for example—remained central to the justification for dwifungsi, the military’s dual political and social role. How has the role of the Indonesian military changed in the post-Soeharto era, and how significant is the military’s present influence in Indonesia? Very early after the demise of the Suharto regime Military Commander Wiranto enunciated ‘ABRIs New Paradigm’, conceding that dwifungsi was no longer sacrosanct. The social and political section of ABRI was abolished and parliamentary representation reduced from 75 to 38. The military no longer automatically sided with the New Order’s electoral vehicle Golkar and would refrain from interfering in political parties. This was a quick and dramatic response to public pressure. As part of the New Paradigm, ABRI was also to confine its role to defence. In April 1999, the police separated from what was known as ABRI and with this separation, came the new name: TNI. On paper it seemed like a lot had changed. Yet we also need to reflect on the fact that generations of soldiers educated during the New Order period were indoctrinated as to the need for a strong military that can intervene in times of civilian struggle. Interestingly, a law on the roles of the TNI and the police attempts to define the jati diri or ’true essence’ of the TNI by the four appellations of a People’s Army (Tentara Rakyat), a Struggle Army (Tentara Pejuang), a National Army (Tentara Nasional) and a Professional Army (Tentara Professional). The concepts of people’s army and a struggle army are terms that refer directly to the military’s role in the 1945–49 independence struggle, which not only look backwards but also form the basis of military claims to political roles. The bill also attempts to uphold the idea of close integration between the people and the military. The law still enabled some forms of military participation in politics by continuing the territorial system |

(which includes a mirror government of military officials down to the village level). This territorial system allows the military to act independently from political authority. The territorial command structure was put in place during the guerrilla war against the Dutch (194–49) and was known as people’s defence system. It was used during the New Order to suppress opposition. The military insists this structure is still important because they say the police are not able to handle serious security disturbances. What we also see in the law is the persistence of a belief that the military should play a role in guiding the nation, which is common to all political armies. There have been many concessions to the need for civilian authority yet it seems the leadership continues to ‘reserve’ the right to resist civilian encroachment into various areas, in particular areas that could legitimately be seen as the domain of defence and security. The military has adapted to the new political landscape but now uses security discourse to legitimise its continuing relevance. Another source of power is via their business interests’, which have not been scrutinised or dismantled. Human rights accountability is another area where there has been very slow progress. So, in practice, the military continues to wield influence. Can you tell us about your present project—Islam and the Politics of Post-Authoritarian Indonesia? This Australian Research Council-funded project is examining how memories of violence shape personal and group identities. The analysis is based on two cases of violence in Indonesia, including the 1965 killings of up to 500,000 Indonesians. Memories of these killings have created parallel ambiguities and conflicts to the much-studied memories of the holocaust in Europe, memories of settler violence in Australia and memories of the Partition in India, but we know far less about how constructions of this past have affected societal attitudes and identities. The project examines competing representations of the past from survivors and their families, perpetrators, historians and members of the younger generation to try to understand how societies, and not just victims, negotiate past trauma. I look at the 1965 anti-communist killings and the 1984 Tanjung Priok shootings. In the first case Islamic organisations were involved in the violence; in the latter different Islamic groups were the victims of state violence. The focus of this study is not the killings themselves, but their significance in national and communal memory. At stake in debates over memories of each case of violence are continuing clashes between the left and right in Indonesia, but also new possibilities of ending these long-standing divisions. In June I co-convened a conference at the National University of Singapore with Doug Kammen, Vannessa Hearman and Anthony Reid, entitled Revisiting the Indonesian Killings. We drew together scholars from Indonesia, Australia, Singapore, the United States and the Netherlands to discuss some of the most recent research on this topic. Inside Indonesia will be profiling some of this research in its next edition. Doug Kammen and I are also editing a collection on this topic to be published by the ASAA’s Southeast Asia series. |

Dr McGregor is a historian of Indonesia in the School of Historical Studies at the University of Melbourne, and the ASAA Council’s Southeast Asia representative. |

|

Media

|

As some of the most dynamic in the developed world, Japan’s media industries—newspapers, magazines, books, television, radio and other media outlets such as the Internet—provide a rich landscape for scholars to view idealised representations of Japanese cultural values.

One example of such a media landscape is commercial television, including the ubiquitous commercial. In one particular kind of commercial, the tai uppua, a musical artist, or artists, is aligned with a product, and the two images are linked, or ‘tied up’. Commonly used since the 1980s, this cross-format promotional practice presents a compressed, multi-layered and potent image to the consumer. The way tie-ups have changed over the years suggests that changes in audience practice affects production of commercials today. Broadly speaking, there are three kinds of commercial styles—often abbreviated to CM in Japanese—in Japan. First, the informative CM, which focuses on production information (‘30 per cent brighter whites!’); secondly, the narrative CM, which tells a story and is often serialised during a single season; and lastly the tie-up where the music and its performance are the focus. Purpose-designed jingles dominated the radio and emerging television industry until the late ’70s, when the tai-uppu (tie-up), imêji songu (image song) or komuson (commercial song) were created. The main difference between a jingle and a tie-up is that the latter is not an anonymous musical expression but |

One of the pioneers of this form of advertising was the cosmetics corporation Shiseido, which successfully tied up with Horiuchi Takao, vocalist of the band Arisu, in 1978. Horiuchi did not appear in the commercial, but in the early days this was not uncommon. The song’s title, however, did appear in the final frame. In the 1970s, million-seller singles in Japan were quite rare, so this single achieving more than 900,000 sales made it a standout commercial success. Years later, the tie-up as a total artistic vehicle

matured into a more complete integration of music, artist and product.

Sometimes the relationship between an artist and a product is ongoing.

Veteran singer-songwriter Nakajima Miyuki enjoyed a long running contract

with Japan Post and was featured as the ‘protagonist’

in a series of commercials for its annual New Years Card campaign

in 1995. Again, she was so well-known that her name did not appear

on screen, but the title of the song did, so that viewers could purchase

the single if desired. This close association between artistic image

and product image has strengthened from the 1970s to the 1990s and

is in line with cultural understandings of media consumption. |

Using television can help to understand popular-culture products and music to frame social ideologies and consumer desires for analysis, but it needs careful theorising to ensure interpretations are rigorous and ‘testable’. Audience theory has striven to demystify the ‘power of the media’ in this way, and interpret these semiotic messages while also understanding their empirical social and economic functions. Television is usually classed using the spectacle performance paradigm: audiences are either mass or diffused1. For the diffused audience, media experiences are so ubiquitous that there is little or only a vague recognition that one is an audience member; rather, the ‘media and everyday have become so closely interwoven that they are almost inseparable’2. Considering the diffused audience, how do we understand tie-up commercials? By 2009, a very successful CM starring SMAP for the mobile phone company Softbank demonstrated that the image of the brand has been deconstructed from the product, the ‘stars’ of the CM and even the music itself. Music and image are still important but the connections between the layers are different—the audience becomes diffuse, as does the imagery. Post-modern life has seen our lives inundated with rapid fire media messages, and its pace is ever increasing. Modernity and technology have accelerated the connections between witnessing, desire and consumer action. Tie-ups provide sensory depth to the process, and

they ‘touch’ the consumer, bringing together diffused

meanings to a disparate audience. That doesn’t mean it is ineffective—it

merely differs in the conceptual relationship between the layers.

Yet the end product can still ‘make sense’ to the audience,

where increasingly the norm is a disparate and diffused world of messages,

meaning and decision-making. |

Dr

Carolyn S. Stevens is Deputy Director of the Asia Institute and

Senior Lecturer in Japanese Studies at the University of Melbourne.

Her monograph, Japanese Popular Music: Culture, Authenticity and Power

(Routledge, 2008) is, in part, based on years of experience working

in the pop music industry in Japan during the 1990s. This article

is based on a paper Dr Stevens will present at the American Anthropological

Association’s 108th Annual Meeting in December 2009.

References

|

||

Obituary

|

The Smiling General’s regime banned any printing or performance of The Struggle of the Naga Tribe, which hilariously pilloried the fictive Kingdom of Astinam’s (read Indonesia’s) Queen (Mrs ‘Ten Percent’ Suharto) and her ministers for their vanity, venality and American diseases. Suharto’s guard of military police arrested him rather than his assailant when Rendra was targeted by a bomber while reciting the even more satirical Snapshots of Development in Poetry from the stage of Ismael Mazuki Theatre. His prosecutors invoked a special Emergency Law that he had ‘provoked the attacker to violence’, and it was the terrorist who walked free while the poet went to gaol. And not for the only time. Rendra’s originality as a craftsman with the words of several languages defies Wordsworth’s effete definition that ‘poetry is emotion recollected in tranquiliity’ (sic), and calls for recognition of the genius he evinced through anything-but-tranquil articulation of authentic and indeed uniquely Indonesian cultural and political priorities in Western literary forms. For example, he not only scripted poems in his own handwriting but, more than any other of several fine proponents of the art among his contemporaries (e.g. his friend Emha, the theologically muscular Muslim bard), he transformed the ‘ho-hum’ convention of schoolboy elocution at Dutch eisteddfods into the robustly political and iconically Indonesian genre of deklamasi, with which they packed the theatres of Jakarta and foreign universities whenever they delivered to the public. My tape-recordings vouch for this artist’s remarkable propensity to draw volcanically creative spiritual energy from his audiences’ inspiration and to compose some of his most inflammatory verses spontaneously as he fired new verbal barrages from the stage at the regime’s prioritisation of ‘Development’ (Pembangunan) over ‘Freedom’ (Kemerdekaan) in the catechism of national commitment. Later in the dressing room, he would be genuinely inquisitive when he asked me to play back lines he had never yet even read to himself so that he could scribble them down for the first time. The specific qualities which constitute Rendra’s greatness as an artist also included the success with which he transcended cultural differences with trans-lingual puns. They helped him (deliberately?) to induce Western novices into an appreciation of Bahasa Indonesia and uncannily to speak that language before they even knew they were doing so. As one illustration of the point, the reader might reflect on the whole of the poem from which the following paragraph borrows a few lines. I refer to ‘Sajak Mata-mata’ (An Ode to Spies), which features in both Potret Pembangunan dalam Puisi (1978) and SOB (1979, University of Queensland Press). Mourners at mortuary gatherings in Australia conventionally request one another to be upstanding and close their eyes to observe a collective silence in memory of the deceased. |

I propose that we will remember Rendra most appropriately by the very opposite of silence and equally respectfully with eyes wide open in rousing declamations of what he wrote even when those who are with us are not all Indonesian speakers. Teachers can do no better than follow his example in providing prospective students of Bahasa Indonesia with such tempting introductions as the following to the distinctive idiosyncratic possibilities of sculpting the language that was clay for his wordsmithing. Consider for instance the duplication which is so well exemplified by a word whose root ‘mata’ means ‘eye’ and which, in the internationally familiar Mata Hari, translates as ‘eye of the sky’ (= sun). As ‘mata2’, the root becomes an expression for ‘spy’ or ‘spies’. In recent months I have introduced my tributes for Rendra in Europe by drawing attention to that simple feature of Indonesian and by inviting my listeners to participate in the articulation of the poem under consideration by quietly voicing the words ‘mutter, mutter’ as a chorus to contextualise my declamation from my own faulty memory of the following excerpts from ’Sajak Mata2’. The opening stanza of his handwritten notes began with an allusion to frustrated newspaper readers urinating provocative gossip on others lower in the political hierarchy as a substitute for the truth which the press muzzled:

I encourage the continuation of the chant of ‘mutter, mutter’, especially to accompany the fifth stanza about censorship and the expression of outrage that:

The italicised and highlighted initial line of this sixth stanza translates as‘The eyes of the people have been “extracted” (like teeth)…by…? And the chorus answers with ‘mutter, mutter’, which harmonises with the declamation’s ‘mata2’. Rendra undoubtedly deserves the tribute that his talents with ball-point and voice really did make the mighty shrink in fear of his art’s quality under Indonesia’s New Order, and it is surely remarkable that it should be the contribution which an Indonesian scribbler and declaimer has made to his country’s cultural heritage that has provided such powerful contemporary evidence that poetry really does matters. (cf Parini, 2008). Future scholarship surely has an obligation to explore such awe-inspiring literary dynamite. |

|

Dr

Miles is a 70-year-old retiree who enjoys poetry while

currently again appreciating the company, coffee and other facilities

in his alma mater (1983–93) Department of Archaeology and Anthropology

at the Australian National University, between appointments as Professorial

Research Fellow at the Centro In Contri Umani at Ascona in Switzerland

and a Research Visitorship in The Cairns Institute, JCU . The CI has

awarded him a grant to conduct further fieldwork among Yao in Thailand

concerning their initiatives in the paragliding industry as an alternative

to opium production. |

||

Review

NAM BANG: MOST SIGNIFICANT AUSTRALIAN-ASIAN EXHIBITION OF 2009Annette Van den Bosch |

| Nam Bang, curated by Boitran Huynh Beattie, Casula Powerhouse, Sydney, April–June 2009, held in conjunction with an international conference, Echoes of a War, on 17–18 April, with the American art critic and historian, Lucy Lippard, as the keynote speaker. The artists exhibited in Nam Bang represented

several generations of conflict and its aftermath as a result of colonisation

and war, immigration, post-traumatic stress and other health effects

on the Vietnamese and the soldiers who fought there. Some of these

issues were the subject of papers in the Echoes of a War Conference. Nam Bang was the most significant Australian-Asian exhibition of 2009 because the range of artworks shown revealed the complexity of relationships between Vietnam and the rest of the world, and their inter-generational impact. The theme of the exhibition included artists whose work ranged from the Vietnam War to the War in Iraq, such as Trevor Woodward, an artist veteran from Western Australia, with his wall of cartoons, Untitled (2009), and Dinh Quang Le, whose interest in the mistreatment of prisoners was sparked by Guantanamo Bay.

Some artists shown have work in the Australian War Memorial Collection, such as Ray Beattie’s Image for a Dead Man (1980), or Nigel Hellyer’s Silent Forest (1996) in the National Gallery of Victoria, while others, such as Bruce Barber’s Remembering Vietnam and We Are United Technologies, both from 1984, were important in the struggle for veterans’ recognition of their ongoing health care issues. Mai Long’s ritual The Burning of Godog 2008 opened the exhibition in defiance of the narrow political interpretation and accompanying demonstration that any of us who have exhibited artwork from Vietnam have experienced from some members of the Vietnamese Diaspora in Australia. Lucy Lippard commented that the most effective social/political work being done today consists of words and images. William Short, an American veteran, artist and curator agreed. He showed six of the photographic portraits accompanied by the text of an interview, from his Memories of the American War-Stories from the Other Side (2009). |

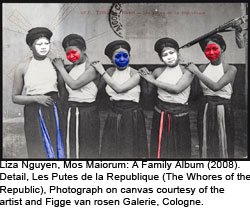

Terry Eichler was conscripted into the Australia Army and in 1968–69 served in Vietnam as an interpreter mainly with 9RAR. Eichler created a subtle photographic work, Meditation on 2,063,500 Deaths (2009), as a memorial to the more than two million Vietnamese and approximately 63,500 people from other nations killed during the Vietnam War. Eichler’s photograph of a group of children in front of old charcoal kilns in the village of Suoi Nghe, taken while on patrol, was overlaid with transparent pages of old Vietnamese notepapers, on which he drew an intricate symbol system. Each symbol stands for 50 deaths. Le Tri Dung, from Hanoi also used words and images in his painting, The Same Pain for Both Sides (2009). In the painting, a deformed foetus is shown at the tip of a banana leaf which divides the composition. On either side, the hats of two soldiers from opposing sides are depicted. Le Tri Dung crosses the boundary of winners and losers and shows the losses for both sides, including from the effects of Agent Orange. Dinh Quang Le, an American Vietnamese artist, interrogated politics, memory, and history’s hidden aspects such as the treatment of prisoners in The Penal Colony: A Mapping of the Mind (2008). His work was a built installation in which visitors experienced a sensory void, and a detachment from reality similar to a cell. His installation videos showed abandoned prison cells in the infamous Con Dao prison, established by the French in 1862 on an island off the coast of South Vietnam to break those who opposed colonialism. The prison passed to the South Vietnamese Government in 1954, to house nationalists and communists who opposed the regime in the south. After 1975 it was used by the communist government to hold failed escapees some of whom subsequently came to Australia. The four-video installation tracked constantly across the prison cell conveying the psychic experience of the prisoner. Liza Nguyen, a French Vietnamese artist presented Mos Maiorum: A Family Album 2008, a series of ten digitally altered French colonial postcards. Les Putes de la Republique, The Whores of the Republic presented five Tonkinese women in exotic costumes. Their faces are painted with the red, white and blue of the Tricolour French flag, with the Moulin Rouge in the background. Nguyen’s critique of the French colonial past in Vietnam in the series of works implies the inevitability of loss of identity, prostitution and exploitation in war and conquest. |

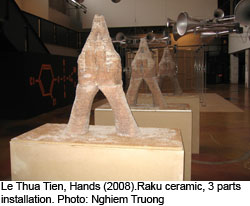

Soon-Mi Yoo, a Korean artist, examined the role of Korean soldiers who fought for the United States in Vietnam in Ssitkim: Talking to the Dead (2004). She used archival and contemporary film footage of interviews to offer an alternative narrative of traditional history. Her film examined the legacy of mass killings of civilians in central Vietnam by Korean forces through documentation and interviews. Her work reveals hidden connections between the suppression of these incidents in Korea and in the global community. My Le Thi Encounters and Journeys (2009) was a video in five parts: Land, Life, Love, Loss and Living. Her work always deals with her personal identity as both Vietnamese and Australian. As a member of the Ede minority who live in Tay Nguyen, the Central Highlands of Vietnam, she was exposed to the fiercest conflicts of the war in her youth. In this haunting work she records the Ching Kram bamboo gongs, the music of Buon Kor Sier, and the singing performances that are so central to the culture of the region. The performances in song and gong music are used to communicate with the spirits of the land and the dead, and at least one other Vietnamese artist Nguyen Thanh Son, has shown his recognition of the cultural similarity between the minorities of Tay Nguyen and some Australian Aboriginal cultural rituals. My Le Thi’s work conveys the celebration and recognition of a cultural heritage which she and other refugees strive to remember. It is fitting to close this brief review of some of the artworks in Nam Bang with the work of Le Thua Tien, who completed his masters of fine art at the college of fine arts, University of New South Wales in 2008. Le Thua Tien is an artist who lives and works in Hue in Central Vietnam, and he too experienced the war’s fiercest fighting as a child, losing his mother and newborn infant sister. His work, Hands (2008) was a monumental sculpture of three pairs of hands in the Buddhist prayer position.

Hands was fabricated in raku ceramic inspired by the architecture and materials of the Hue citadel and the tombs and pagodas along the Song Huong. The three pairs of hands also represent the three regions of Vietnam—north, central and south—which were depicted in traditional imagery as three maidens. The three figures in a row speak of reunification and reconciliation, and the Buddhist triad, past, present and future, recognising, says Le Thua Tien, ‘what has been, what we have experienced and how we can change the future’. |

Dr

Van den Bosch is an Adjunct Research Fellow at Monash

Asia Institute. Her article 'Professional Artists in Vietnam: Intellectual

Property and economic and cultural sustainability' was published in

the Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society 2009, vol. 39, issue

3, pp.221–236. |

||

Student of the Month

Along

the way, Delmus has studied sociology at Flinders University and anthropology

at the University of Aberdeen to improve his understanding of Islamic

scripture and the traditions of the Prophet, which he lectured in

at Manado. Along

the way, Delmus has studied sociology at Flinders University and anthropology

at the University of Aberdeen to improve his understanding of Islamic

scripture and the traditions of the Prophet, which he lectured in

at Manado. His study of sociology taught him that Muslims’ interpretations of their religious duties are influenced by their cultures, whereas his studies in anthropology reminded him that all Muslims necessarily differ from one another, since each perceives Islam in different ways. These educational experiences encouraged him to look at Islam from another perspective, namely politics, and for his PhD program he is now looking at the relationship between transnational Islam and state structure in West Sumatra. Although the Islamic term for the focus of this study is ummah, an imaginary Islamic community, current studies have used the term ‘transnational Islam’ to try to capture Islamic networks that cross national boundaries. Scholarship to date has focused mainly on Muslim migrants in Western countries. This is unsurprising since a significant number of the many Muslims who have migrated to Western countries in the past 50 years have maintained their Islamic cultures in their new environments. Delmus’ research, however, shows that transnational Islam is not restricted to the movement of ideas and people across Islamic communities, but also to the movement of finance and to responses to particular events related to Muslims across borders. In Indonesia’s case, students throughout the archipelago have studied Arabic and Islam free of charge from a Saudi Arabian-funded college in Jakarta. The Organisation of Islamic Conference has helped the Indonesian government to apply for Islamic trade financing on imported oil so that it can pay its bills in six to 12 months, rather than the one month available to them outside the Islamic financial system. In 1999, the The Islamic Development Bank bought shares of the Muamalat Bank of Indonesia to avoid bankruptcy during the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–98, and hundreds of mosques have been funded by the International Islamic Relief Organisation (IIRO). Meanwhile, many Indonesians have shared an increased feeling of difference with the West since the 9/11 attacks on the United States. As in other parts of the Islamic world, the negative use of Islamic symbols, such as the infamous Danish cartoon and the film ‘Fitna’, have deepened Indonesian Muslims’ antipathy to Western countries, while wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have strengthened feelings of solidarity with other Muslims. Unlike many scholars who focus on the influence of transnational Islam as the primary force in developing cross-border Muslim structures and communities, Delmus positions himself with those who examine the interplay between transnational Islam and state structures. It is clear at both the national and sub-national level, he says, that state officials have sought to mobilise—and to a significant extent, co-opt and control—aspects of Islamic practice that have traditionally fallen outside the reach of the state. |

Recognising the potential benefits of proximity to other Muslim communities in the region— including the many Malaysians who have come to study and for holidays in West Sumatra—and the potential for Islamic investment from the Middle East, local officials have sought to facilitate economic flows through Muslim-friendly financial and investment networks. For example, the World Islamic Economic Forum funded regional projects in agriculture and tourism in 2009, while investors from the United Arab Emirates came to Padang to arrange their investments in the same year. In response, the regional government has facilitated the establishment of Islamic banks and Islamic units in conventional banks in the region as students and tourists from other Islamic countries wish to use Islamic financial systems. Ritual and social practices have also become the focus of increased regulation, as is evident in local laws that assume responsibility for collecting and distributing the religious tax zakat, designed to channel money either from local or overseas Islamic communities into poverty-related projects. Perceptions of increased religiosity in the community have led to the mandating of Islamic dress and Islamic education in public schools by local officials. Delmus grew up in a small village in West Sumatra, but his PhD project has required him to spend extended periods in the field, examining his home territory with fresh eyes. In 2008, he spent five months observing changes in local practice, collecting documents detailing the influence of transnational Islam in the province, and talking to state officials, politicians and Islamic leaders about the regional state’s endorsement of Islamic structures and laws. He is planning to go back there in 2010 for another field trip to supplement the data he gathered during his previous visit. In the meantime, Delmus is enjoying Australian academic

life and doing his PhD. His supervisor, Dr

Michele Ford, gave him an opportunity to tutor in a language class

this year and encouraged him to join the organising committee of the

Indonesia Council Open Conference, where he also had the opportunity

to present a paper and chair a panel session. He has learnt a lot

that he can take back to his research and teaching in Indonesia from

these experiences. |

| Delmus Salim is doing PhD at the University of Sydney. | |

ASAA News

|

The annual prize of $1,000 is 'to encourage and reward excellence in scholarship on Asia at the doctoral level, to publicise the best young Australian scholarship on Asia, and to encourage its publication in Australia’. Assistant Professor Nanlai Cao, from the Hong Kong Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences, received a PhD in anthropology from The Australian National University in 2008 for his thesis entitled ‘Constructing China’s Jerusalem: Christians, Power and Place in Contemporary Wenzhou’. The thesis provides ethnography of the massive Christian resurgence in Wenzhou, which has become the largest urban Christian centre in China, popularly known as ‘China’s Jerusalem’. ‘Wenzhou has also been a regional center of global capitalism since the 1990s,’ said Nanlai. ‘The Christian revival there has taken place under the conditions of a modernising state, lax local governance, an emerging capitalist consumer economy, and greater spatial mobility among individuals. ‘In the post-Mao era, Wenzhou Christianity constitutes a popular participatory domain in which a great diversity of people articulate their subjectivities and interests and interact with one another through belief, he said. Through the lens of Wenzhou Christianity, Nanlai explores the nature of religious participation in the political economic context of post-Mao reforms, reforms that emphasise a rationalised modernity and in which economic growth dominates all spheres of social life. Departing from a dichotomous view of state domination

and church resistance, he shifts the focus from a narrowly conceived

institutional narrative of Christian revival to an analysis of the

larger cultural processes |

Rather than assume monolithic attitudes on the part of any Chinese Christian group, he explores the diverse ways people in different social positions, individually and collectively, construct their religious and social identities. In particular, he shows how the vitality and complexity of Wenzhou Christianity is inextricably intertwined with class positions and dispositions, gender differentiation, and place distinction in the practices of everyday life embedded in the regional capitalist context. ‘While the church offers a site for the formation of new social experiences and cultural identities among local groups of varying backgrounds, the core of Wenzhou Christianity is a movement of an upwardly mobile class of private entrepreneurs that has emerged alongside the rapid urbanisation and industrialisation of the region,’ he said. ‘The Wenzhou story demonstrates that the presence of an organised business community at the grassroots level can not only negotiate changes in church-state relations but also move Christianity from the margin to the mainstream of Chinese society in everyday manoeuvres.’ By examining multiple subjective positions involved in local Christian revivalism, Nanlai argues that Wenzhou Christianity, far from being a coherent symbolic universe, is a historically complex regional construct framed by a moral discourse of modernity in which emerging socioeconomic groups struggle to negotiate their social statuses and to refashion and legitimate their identities. ‘It is in the context of a homogenised vision of modernity that the story of Wenzhou Christianity finds its wide resonance in contemporary Chinese society,’ he said. Nanlai Cao’s articles have appeared in Sociology of Religion: A Quarterly Review, The China Journal, and China Perspectives. |

|

*Since 2004, the President’s Prize has been augmented by the DK Award, presented by the global book distributor, DK Agencies of New Delhi, to highlight its dealings with Australian academics and academic libraries since 1968. Nanlai Cao’s

research was funded by the Australian National University, the Society

for the Scientific Study of Religion, the Religious Research Association

and the Association for the Sociology of Religion. He wishes to express

his deep gratitude to his dissertation committee—Andrew Kipnis,

Philip Taylor and Nick Tapp—and ANU's Athropology Dpartment

(RSPAS) for intellectual guidance and nurturance. |

||

ASAA PRIZE FOR EXCELLENCE IN ASIAN STUDIES |

ASAA 2010 UPPDATE |

| The ASAA is calling for submissions for the ASAA Prize for Excellence in Asian Studies, awarded biennially to a mid-career researcher or researchers for research on an Asian subject, as represented in a book or a portfolio of articles and/or book chapters. Individual or joint candidates may nominate, or be nominated, and must be ASAA members employed at an Australian University below associate professor level at the time of application. They must also have completed their PhD at least five years before lodging the application. Applicants are required to submit a scholarly book

not based on a thesis, or 10 chapters or journal articles published

in the five years before the application is submitted. If joint candidates

submit a portfolio of articles and/or book chapters, at least six

must be co-authored and 50 per cent of the remaining articles and/or

chapters must be single-authored by each candidate. Submissions for the 2009-10 round must reach the

ASAA Secretary by 10

December 2009 and be in hard copy, accompanied by a cover letter that

outlines the applicant’s/nominee’s claims to eligibility. |

Planning for the 2010

Asian Studies Association of Australia 18th Biennial Conference is

well underway and will be held from 5–8 July at the University

of Adelaide, in the heart of the Adelaide’s shopping and dining

district.

Proposals for panels and individual papers are welcome, and 14 panels have already been announced on the conference website. Some of the confirmed conference speakers include:

Registration will open in early December and further

details will be announced on the website. Further

information. |

Recent Interesting Books on Asia

|

Contributed by Sally Burdon Christmas giving provides the ideal opportunity to the spread understanding about Asia. This month we feature a small selection of books, from a huge range of possibilities, that would make great gifts. |

|

|

Chun Injoo Colour photographic illustrations, 112 pages, index, paperback, Periplus, Singapore, 2004. ISBN 9780794605032. $19.99 Recipes for raw Korean beef tartare salad, chilled summer noodles, classic kimchi stew, grilled eel, fried kimchi rice and other signature dishes of Korea can be found in this fabulous cookbook. With tempting colour photographs and easy-to-follow instructions, cooks everywhere can master these recipes in no time. Essays about the culture and history of food in Korea and a glossary of typical ingredients used in local cooking help the reader to understand the culinary traditions of Korea.

Robin Ruizendaal, Hanshun, Wang, Lin, Paul. Over 300 pages, profusely illustrated in colour, quarto, dustjacket, Thames & Hudson, UK, 2009, ISBN 9780500514900. $95 This stunningly illustrated book introduces for the first time the beauty of theatre puppets from all major Asian traditions, taking the reader on an inspiring journey through hundreds of years of craftsmanship and creativity in nearly 350 glorious photographs. Asian Theatre Puppets will have immense appeal both to audiences with an interest in the Asian arts, as well as to the general reader, as it opens up a realm of artistic expression that has hitherto largely unknown in the West.

Helen McCarthy and Otomo Katsuhiro colour and black and white photographic illustrations, 272 pages, index, bibliography, notes, hardback in protective plastive cover, plus dvd, Ilex, UK, 2009, ISBN 9781905814664. $65 Osamu Tezuka has often been called the Walt Disney of Japan, but he was far more than that. Tezuka was Disney, Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Tim Burton and Carl Sagan, all rolled into one incredibly prolific package, and he changed the face of Japanese culture forever. This book reveals what makes him one of the key figures of 20th century pop culture. Packed with stunning images, many never before seen outside Japan, it pays tribute to the work of an artist, writer, animator, doctor, entrepreneur and traveller whose insatiably curious mind created two companies, dozens of animated films and series, and over 150,000 pages of comic art in one astonishingly creative lifetime. This is an amazing adventure for the manga and anime neophyte, an essential reference for the confirmed fans and a visual treat for anyone who loves art.

Roma Tearne 409pp, paperback. Harper Press. London, 2009, ISBN 9780007301553. $27.99 A gripping and moving novel set against the background of the conflict in Sri Lanka. It deals with the feelings of loss and displacement caused by immigration when forced to leave and live a new life in alien London. Recommended. |